Venezuela's debt hell...

While Hugo Chavez talks a beautiful left-wing game, his policies have pushed Venezuela into a massive and unnecessary debt crisis. The government’s ongoing money problems make it impossible to fund the social agenda Chavez never shuts up about, and have triggered a socially disastrous spike in inflation. What’s worse, the government was warned again and again that this would happen, but simply dismissed critics. Bushwhackers would do well to note the parallels here, in terms of deafness to criticism and fiscal recklessness.

At some point, you have to step back from the rhetoric and say, “ok, yes, but what’s the government actually doing, in terms of policy, and what impact are those policies having on people?” Words are nice, but sometimes you have to look at the numbers.

It’s little wonder revolutionaries seldom stop to do so: the answers are not kind to them.

Last October, Descifrado posted this fascinating, bone-chilling gloss on Central Bank economist Jose Guerra’s projections for public finances in 2004.

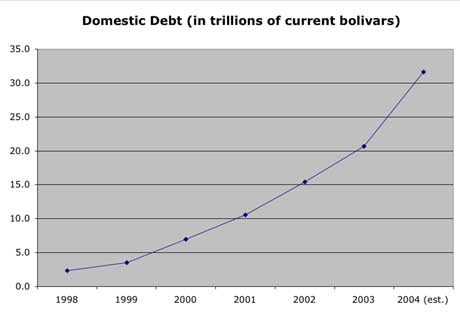

Guerra says that if the government borrows as much money as it has said it wants to borrow from the internal (i.e. bolivar denominated) credit markets in 2004, its total domestic debt would rise to 36.1 trillion bolivars – a fifteen-fold increase on the Bs.2.3 trillion domestic debt Chavez inherited when he reached power.

Even in terms of dollars, the growth of the domestic debt is staggering: by the end of this year it could total $16.1 billion (figuring the bolivar at the officially projected Bs.1950:$.) That’s four times as much as the $4 billion debt Chavez inherited in 1999. The domestic debt, if things continue to go this way, will be worth 20% of GDP: a fifth of the value of the economy, by the end of 2004.

But that’s not the worst of it.

The worst of it is that most of this mountain of new debt has come in the form of short term treassury bills, at very high interest rates – often 25-30% a year. As Venezuelan banks became more and more exposed to the government, they became less and less willing to buy long term DPN bonds: they needed their money back in 3 or 6 months, not 3 or 4 years.

As anyone who’s gone a bit overboard with credit cards knows, high-interest short-term borrowing quickly snowballs out of countrol. Compound interest is a merciless foe. And the very high interests the government has been paying for these short term loans have sent the domestic debt spiraling out of control.

Source:

Finance Ministry Website

The payment schedules that result when a debt is growing this fast are brutal.

The government’s obvious response is devaluation. If you owe Bs.1,600, and the exchange rate is Bs.1,600 to the $, then you owe $1. But if you devalue the currency – if you let the exchange rate slide to, say, Bs.3,200 to the dollar – you find that under the new exchange rate those Bs.1,600 you owe are magically only worth 50 cents! Your bill has been cut in half! And since most of your income is in dollars (think oil), you have an obvious interest in “watering down” the domestic debt by letting the bolivar devalue more and more against the dollar.

An out of control domestic debt is an inducement to aggressive devaluation.

Problem is, each time the government devalues the currency even further, the result is more inflation. And inflation is devastating for people on low incomes.

The irony is that, when you look at it closely, the revolution’s economic management turns out to be deeply regressive, even reactionary. Everyone is losing, yes, but proportionally, the poor lose more of their purchasing power than the rich do. The reason is simply that the rich have savings in dollars, so they can shield themselves from the ups and downs in the bolivar’s value.

The poor don’t have that privilege: they live day to day. When you’re on a fixed income, living close to subsistance level, price rises of 25 or 30% or more each year mean hunger. In the barrios, inflation is not some distant macroeconomic aggregate, some abstraction. In the barrios, inflation means destitution. It means eating two meals a day, when you used to be able to afford three, or just one meal a day if you used to eat two. It means giving up breakfast.

These are the kinds of sacrifices that a broad swathe of the working class people who voted for Chavez have had to make. Chavez’s strategy to borrow-and-spend his way to social justice has been a disaster for them.

Sadly, the government just doesn’t have the money to take the sting off: it’s all going to service the mushrooming domestic debt. Debt repayment now dwarfs the president’s social agenda in the government’s spending priorities. Guerra projects that domestic debt service payments alone could gobble up a shocking 94% of the government’s huge oil revenues. That’s nearly all the money from the country’s fabled oil industry up in smoke, just like that, just to service the debt.

Populist “misions” make for nice headlines, but the cold hard figures tell a different story. Guerra forecasts the government will spend 57% more on servicing its domestic debt than it spends on all public investments put together – things like building new roads, schools, hospitals, and such. The domestic debt service will cost nearly as much as total state spending on education, health and social security all put together (87% as much.) In fact, debt service will cost 43% of all current government income.

Servicing the domestic debt has become so expensive that even if the government had a sensible and coherent plan to tackle poverty – which it emphatically doesn’t – it wouldn’t matter: there simply isn’t enough money to pay for it. Nearly half of what the government takes in goes to service the debt; what’s left is barely enough to pay the public sector wage bill.

Belatedly, the government has accepted the arithmetic impossibility of continuing along the current path: there just aren’t enough bolivars in the banks to keep borrowing in Venezuelan currency. Instead, they’ve started to do what critics told them to do all along: borrow dollars and swap bolivar obligations for longer term dollar bonds.

It’s too little, too late. The first of the swaps was for just $1 billion – to yield a frightening 10.25% (in $$$!) That leaves another $15 billion to go, and it’s hard to imagine international markets making that kind of money available this year. The government’s refusal to switch to dollar borrowing earlier has already cost this poor country billions of dollars – the damage is done.

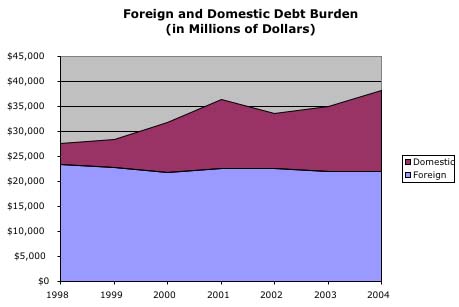

To put it another way, the Chavez’s government’s pigheaded incompetence has saddled a whole new generation of Venezuelans with debt. The total debt burden (foreign and domestic) has jumped 45% in 5 years, in dollar terms, from $25 billion to $36.4 billion.

Sources:

Finance Ministry Website

Central Bank of Venezuela Website

Jose Guerra estimates, cited in Descifrado

If the government’s swap strategy works, you’d see the blue part of this chart swallow up much of the purple part as the government “swaps” domestic bonds for foreign ones. The total will not fall as a result, though the repayment schedule would be far less murderously onerous.

The worrying part is that the government will now be tempted to devalue the bolivar before swapping any more bonds. This would allow it to buy back more bolivar debt with fewer newly borrowed dollars. Again, that would just be a way of passing on the costs of the government’s failed strategy to the population as a whole – via inflation.

It’s just sad.

The net result of all this rather icy technocratic talk is real suffering in the barrios and towns of Venezuela. The government’s money crunch means less money for all the things that could help people out of poverty: less for social programs, less for schools, less for hospitals. Meanwhile, people’s needs only grow: more hunger, more unemployment, more destitution, more desperation.

And all for no good reason at all. All to make some ideological point about not needing the IMF, about being able to tough it out without international credit markets. As with any revolution, in chavismo ideological purity comes first; the needs of the people are an afterthought.

The thing that drives me and other government critics crazy is that WE TOLD THEM SO! I’ve been writing about this topic for five years now, only usually in the future tense, warning that the things that are happening would happen. Dozens of independent economists can say the same. We tried to explain to the government why this strategy would not work, we shouted ourselves hoarse trying to get them to understand that these policies would end up screwing the very people Chavez wanted to champion.

We wrote about it again and again, warning that the borrow-in-bolivars-only strategy was unsustainable, short-sided and stupid, explaining again and again that domestic credit markets were not deep enough to bankroll the government, drawing out the social implications of this course of action, appealing even to the government’s sense of self-preservation by explaining to them that the strategy would cripple their ability to finance Chavez’s social agenda.

The government interpreted our protests as the “squeals of pigs being taken to the slaughterhouse” – just the protestation of an old elite worried about losing its privileges. They took our criticisms as evidence of the revolutionary bona fides of their policies. We were variously dismissed, ignored, mocked, attacked, derided and generally disregarded as “savage neoliberals.”

Now, billions of wasted dollars later, it’s not the independent analysts who lost out. We’re sure as hell not going to bed hungry. For the privileged, the crisis means being able to afford only one maid instead of two, or having to hang on to a 5 year old car for another couple of years before changing models. They’re not the ones bearing the brunt. It’s the millions of poor Venezuelans who believed Chavez when he promised them a better life who are bearing the brunt.

They’re the ones who’ll go to bed on an empty stomach tonight.

—

Late addition

In today’s El Universal, Emeterio Gomez urges the opposition to do a bit of a mea culpa, before pilloring Chavez’s economic management. From 1973 through 1998, he points out, the opposition did the exact same thing Chavez is getting raked over the coals for doing now.

Point taken.

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 22 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate