The Untold Story of Venezuela's 2002 April Crisis

The conventional wisdom about Venezuela’s brief coup attempt in April 2002 is almost entirely wrong. The real story is much weirder, and much more interesting.

The events that gripped Venezuela from April 11th to April 14th, 2002 will keep historians busy for decades to come. In the space of four days the country cycled through three presidents. Venezuelans watched appalled as an elected official emptied his gun in the direction of an opposition march in broad daylight. They saw tanks rolling on the streets of Caracas, they heard the armed forces’ top-ranking general announce the resignation of President Chávez, and they saw a right-wing clique take total control of the state. The private TV and radio stations that could have covered the chaos were first shut down by the government and then conspired to suppress the news of his return. It’s a lot to cover in a single essay.

First, a note of caution. The task of demistifying the coup is made especially difficult by the thick layer of propagandistic undergrowth that now clings to nearly every aspect of the story. Since 2002, polite opinion outside Venezuela has hardened around an impossibly simplistic version of events, one that fits in snugly with first world perceptions of Latin America as an entirely passive CIA stomping ground, where an all-powerful US makes all the important decisions and the “natives” grin and bear it.

It’s not surprising this account has gained such a wide following. It spares people the trouble of having to learn about the details of the crisis that led to the coup. It exempts time poor/indignation rich readers from having to wade through a mass of incomplete, often contradictory evidence on their way to a nuanced, evidence based understanding of what happened. And, of course, it has a powerful and extremely well funded patron in the Venezuelan government itself. Helped along by the tireless propagandizing of The Revolution Will Not be Televised and Eva Golinger’s Chávez Code, as well as by Chávez’s own politically motivated endorsement, this version now dominates first world accounts of the coup.

Only trouble is, it’s almost totally wrong.

The alternative account you’ll find here is evidence based and, unavoidably, pretty long. There’s just no way to convey what happened in 800 words without massively distorting the story. And whether you favor the Chavez government or oppose it, there’s no way to understand what actually happened without throwing some cherished but unsustainable certainties in the pyre. The truth, I’m afraid, makes for some uncomfortable reading for both sides.

Much of the material the following is based on comes from Sandra La Fuente and Alfredo Meza’s excellent book El Acertijo de Abril (The April Riddle) – an oasis of fair reporting in a sea of political propagandizing on the subject. The two have worked hard to produce a book of confirmed facts, not spin or supposition. Of course, any errors are mine.

An atypical coup

Though the psychedelic four-day whirlwind of events is commonly described as a “short-lived coup,” or a “failed coup attempt,” the word “coup” obscures as much as it reveals about the April Crisis. At the heart of this convoluted story is an attempt to implant an unconstitutional government, for sure. It’s no less true that the April crisis witnessed a series of events that fall completely outside the territory of the traditional Latin American coup d’etat. Who ever heard of a Latin American coup where the coupsters “forget” to gain military control over the seat of government? Where they have no overall plan, improvising minute by minute as they go along? Where the overthrown president worked extra-hard to provoke a confrontation? Whatever April 11th was, it was not your typical, 50s style CIA-hatched plot.

So what actually happened?

Factor #1: The March

By 9:00 am on April 11th, it was already clear this would not be a normal day. A very large number of Caraqueños had gathered to demand the president’s resignation. The crowd, variously estimated between half a million and 800,000 strong, came out on just 12 hours notice. It was, then, the single largest political demonstration in Venezuela since 1958.

The April 11th March: Unprecedented

Why did several hundred thousand people decided to march to demand the resignation of a president they had democratically elected twice, by huge majorities, in the preceding 3 years?

Without going into a long detour on just how it is that the political crisis caused by the appointment of seven leftist academics and bureaucrats to the board of the state oil company, PDVSA, caused a crisis capable of escalating so explosively, I’ll say that April 11th was the culmination of five months of increasingly vicious political fighting between the government and the opposition.

The opposition accused the government of seeking to impose an elected dictatorship, while the government saw the opposition as a cabal of reactionary wreckers. By early April, the sense of crisis was palpable, with Venezuelans riveted to the unfolding political drama.

Throughout the crisis, President Chávez gave free rein to his trademark hyper-confrontational style. The perception at the time in the opposition camp was that the government was consciously seeking to provoke a crisis.

Two years later, Chávez confirmed this perception explicitly, in a speech to the National Assembly. He boasted that, having failed to capture complete control of the oil bureaucracy in his first three years in power, he had worked out a plan – Plan Colina – to escalate the PDVSA conflict, and appointed a task force to focus on this goal. By raising tensions to unprecedented heights inside the company, Chávez hoped to identify and flush out all those who did not back him unquestioningly. “Sometimes it is necessary to provoke a crisis,” he said.

It worked.

Chávez’s belligerence grew throughout early 2002, culminating in his theatrical firing of seven top PDVSA officials who had resisted the new board appointments. The private media responded in kind, showering the country with highly inflamatory anti-government propaganda around the clock. By April 9th, when the opposition-run National Labor Federation and Employers’ Federations called a General Work-Stoppage, basic civility had completely broken down. Each side vowed to crush the other. The private airwaves were dominated by anti-government propaganda, and Chávez used his power to “chain” the national broadcast media (i.e. to force them to all broadcast government messages live) to an unprecedented extent. By my count, there were over 20 such “cadena” broadcasts on April 9th alone.

That the opposition media gave up any notion of journalistic balance in attacking the government can’t really be denied. At the same time, the storm of attacks was just what Chávez had been seeking. Plan Colina can be seen as an effort to systematically piss off government critics in the media, the unions, the Catholic Church, and any other institution he could not control.

To understand the confrontational extreme the government had reached, consider this: the proximate cause of the crisis, in April, was the appointment of that new PDVSA board. On April 10th, sensing the mood of national emergency, the newly appointed board members tendered their resignations to Chávez. Had this gesture been made public, it might – might – have been enough to defuse the whole crisis. But Chávez – following the old maxim of the-worse-it-gets-the-better-it-gets – chose to keep their offer under wraps. Within 24 hours, he had hundreds of thousands of protesters on the streets of Caracas.

Factor #2: The Bait-and-Switch

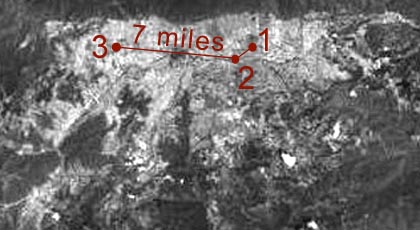

The opposition protesters brought together on April 11th did not know they were about to set off on an insurrectional adventure to the presidential palace. They believed the march would last just a few kilometers, from Parque del Este Metro station to the PDVSA building in Chuao. Both are on the East side of Caracas, 7 miles east of Miraflores Palace, which sits in the Central district to the west of the city.

Satellite Photo of Caracas

1-March Starting point – Parque del Este.

2-Advertised end point – PDVSA Chuao.

3-Real end point – Miraflores Palace.

What happened? In the months after the crisis, testimony given in the National Assembly revealed that opposition leaders had planned to pull a risky bait-and-switch on their own supporters. The night before the march, they had agreed that once they reached PDVSA Chuao they would call on their followers to march west, the entire way to the presidential palace. The decision to re-route the march would be presented as a spur-of-the-moment thing, and given the extremely emotionally charged atmosphere of those days, there was no doubt that the marchers would follow their leaders west.

To me, one of the most interesting revelations in Sandra La Fuente and Alfredo Meza’s El Acertijo de Abril is that the government knew of this plan by the evening of April 10th. An agent from the Asamblea Popular Revolucionaria (the people who bring us Aporrea.org) “Directorate of Social Intelligence” learned of the planned detour and transmitted the news back to headquarters.

The government clearly had to protect itself from what was, without exaggeration, an insurrectional march. From a public-order point of view, the problem was not difficult: Chávez continued to command the Guardia Nacional – a military-run internal security force along the lines of the Gendarmes in France or the Guardia Civil in Spain – which is trained and equipped to deal with public-order problems.

With 12 hours advance notice, it would have been easy for the Guardia Nacional to block the march route to Miraflores. Simply by blocking off the end of Avenida Bolívar, the Guardia could have kept the marchers a safe distance away from Miraflores. The march would have turned into another of many political rallies. There would have been speeches and slogans, and eventually the marchers would have packed it in and gone home.

This is not how Chávez reacted. Instead, he came up with a two-pronged plan to defend the palace.

First, his political machine – again led by the Asamblea Popular Revolucionaria – gathered some 3,000 supporters to surround Miraflores for a counter-demonstration to face down the opposition marchers. La Fuente and Meza confirm that guns were handed out by pro-Chávez politicians to the crowd, but only after the shooting started.

At least a handful of those Chávez supporters were caught on video shooting south, apparently in the direction of the opposition march. Though it is not clear – because no serious investigation was ever carried out – whether those shooters are responsible for the deaths down below, it’s plain that much of the chavista self-defense strategy relied on deploying armed civilian supporters around Miraflores. So much so that the Presidential Guard Regiment had set up a field hospital to prepare to treat casualties in the parking lot of its Palacio Blanco headquarters, just across the road from Miraflores.

Factor #3: Plan Avila

The decision to arm government supporter’s outside Miraflores was serious enough, but it’s the second part of the government’s reaction that really got Chávez into trouble with the army.

At 10:30 am, according to recordings of military radio frequencies made by opposition supporters, Chávez personally ordered the activation of Plan Avila. Now, those two words will mean little to foreign readers, but they will send chills down the spine of any Venezuelan.

Plan Avila is an army-run contingency plan designed to quell serious disturbances in Caracas.

As far as I know, the plan had only ever been activated once before, during the massive looting that broke out on February 27th and 28th, 1989. The police and the Guardia Nacional had been overrun by the riots, and the decision to deploy the army with orders to shoot looters on sight resulted in a bloodbath.

The army killed at least 277 people during Plan Avila ’89, perhaps as many as a thousand, giving rise to the first wave of home-grown human rights NGOs in Venezuela. Cofavic, the Victims and Family Members Committee set up to help the relatives of the victims, spent years pushing for an international human rights investigation headed by OAS’s Inter-American Human Rights Commission. Eventually, the commission found against Venezuela, ordering the government to pay restitution to the families of the victims. The court also ordered Venezuela to disclose the operational details of the plan, previously protected by military secrecy laws, and to bring Plan Avila into line with international human rights law.

The Chávez government, which was already in power when these decisions were handed down, failed to implement either of the Interamerican Commission’s decisions.

[For the sake of brevity, I’ll spare the reader an angry tirade about the rank hypocrisy revealed by the government?s failure to implement the IHRC ruling, given that Chávez spent 10 years using the 1989 massacre as a political hobby horse, calling it a demonstration of the old regime’s callous disregard for human rights.]

So, contravening the IHRC ruling, and contravening his own constitution that clearly bans the use of fire arms to control civilian demonstrations, Chávez called out the troops. The Venezuelan army has no riot gear, no non-lethal weapons at its disposal, no training in crowd control: just semi-automatic rifles packing live ammo.

Not surprisingly, the order to activate Plan Avila set off alarm bells in the military establishment. If the plan had been controversial in 1989, when it was deployed to control violent looting by armed groups of people, its application against a huge political march made up largely of unarmed civilians threatened a Tiananmen Square style political massacre.

By a quirk of fate, April 11th, 2002 was also the day when the International Criminal Court Treaty came into force worldwide. With the arrest of Pinochet in London fresh in their minds, top officers were only too aware that human rights abuses have no statute of limitation.

To their unending credit, the two key military officers at the top of the Plan Avila chain of command simply refused to follow the president’s orders. As confirmed by the subsequent hearings in the National Assembly, this is the key decision that set off the chain of events that weekend.

Factor #4: Rosendo and Vásquez Velasco

Who were those two officers, and why did they act the way they did? Was their disobedience part of an insurrectional plot? Were they U.S. stooges? Or did they act on principle?

Left to right: Generals Vásquez Velasco, Rosendo and Garcia Carneiro

Mayor General Manuel Rosendo, a personal friend of Chávez and one-time baseball teammate, was head of CUFAN, the Armed Forces Unified Command. General Rosendo was largely seen as a Chavista hardliner until that afternoon. Then a hate-figure in opposition circles due to the openly political speech during the Independence Day celebrations in July 2001, Rosendo was considered a member of the chavista inner circle.

After the crisis, General Rosendo testified to the National Assembly had participated in a contingency planning meeting with Chávez, his cabinets, and members of his party on April 7th. At that meeting, the politicians first aired the plan to mobilize armed civilians to protect the presidential palace in case of major trouble. At the meeting General Rosendo pleaded with the president not to allow such paramilitary tactics into Venezuelan politics, sensing the potential for bloodletting. Chávez dismissed his concerns.

On the 10th, just a day before the coup, Rosendo sent a long, emotionally charged letter to Chávez beseeching him to establish a dialogue with the opposition leaders to defuse the brewing crisis. Rosendo was not aware of Plan Colina, or he would have known that Chávez’s policy of relentless escalation had been decided long before.

His position matters because, legally speaking, it is the head of CUFAN who must hand down the order to activate contingency plans like Plan Avila. When the order came, Rosendo balked.

Then there was Mayor General Efrain Vásquez Velasco, the Commander of the Venezuelan army. Seen as a moderate until that point, Vásquez Velasco was on good terms with the government. Neither Rosendo nor Vásquez Velasco could seriously be considered coup-plotters: intensely spied on by chavista intelligence officers, they had been judged trustworthy enough to keep in key command posts.

It later emerged that Vásquez Velasco had once met with one of the people later revealed to have been deeply enmeshed in an anti-government conspiracy – former Foreign Minister Enrique Tejera Paris. All accounts of the meeting agree that the second Tejera Paris obliquely floated the possibility of a coup, Vásquez Velasco simply got up and left the room. Certainly, looked at closely, Vásquez Velasco’s decisions that weekend were not those of a man angling for power himself, or of one working closely with the coupsters.

These were the two people whose decisions precipitated Chávez?s fall later that night: two very high-ranking army officers trusted by Chávez, who balked at a patently unconstitutional order.

You can tell a lot about the intellectual honesty of any account of the coup you read by its handling of the Plan Avila episode. The standard chavista version of the coup simply omits mention of it altogether. Despite the mountains of testimony and documentary evidence on the central role of the Plan Avila order in cracking the military chain of command, the official version simply ignores it, while placing the bulk of responsibility on a supposed American intervention backed by uniformly circumstantial, roundabout evidence.

To recall the earthquake unleashed by the Plan Avila order is not, however, to say that there was no military conspiracy afoot that day. As shown on the private TV stations on April 12th (and, with great glee, in The Revolution will not be Televised) there surely was a conspiracy – several conspiracies, in fact – led by lower-ranking army soldiers, guardia nacional and navy officers who were horrified by Chávez’s evident authoritarian streak. It is nonetheless true, however, that the watershed event of the day, the decision to disobey the Plan Avila order, was not made by the conspirators, but by members of the chavista inner circle unrelated to them. The conspirators swung into action only later that night, once Vásquez Velasco and Rosendo had forced Chávez into a corner. But let?s not get ahead of ourselves here.

My April 11th

I spent most of April 11th running around Caracas with a camera crew – consisting of my friend Megan with her Cannon XL1, and our jolly oversized Scottish translator/bodyguard Hamish. We were working on a freelance project when the crisis broke. Alas, we were not inside the palace.

April 11th March: Chuao

At 11:00 am, we were in Chuao when the march leaders ‘spontaneously’ announced the change of route. I had to be at my newsroom by 11:30 to write VenEconomy’s daily 2-minute radio spot for RCR, to be broadcast an hour later. I took a taxi back to the office, and in a feverish hurry wrote a spot warning that the country would need to give itself a new government and that this new government needed to be as broad-based as possible, including even moderate chavistas (miquilenistas), in order to have any credibility or staying power.

I include that tidbit not just for the gloating rights. I include it to show that even that early in the afternoon, before the killings and the military about-faces and the rest, it was clear that the popular mobilization against Chávez was too widespread to simply go away somehow. It was also clear (to me, anyway) that the government had hours to go, and that whomever replaced Chávez needed to take the high road if it was to have any credibility and staying power at all. They didn’t, and the rest is history.

Radio-spot duly written, I caught another taxi and went right downtown to meet the crew at Avenida Bolivar, where I figured the marchers would arrive at 2:00 pm or so. Three hours for a seven-mile march seemed about right to me. We sat down to keeping one eye on the TV sets, but before we’d quite finished, we saw the first few marchers beginning to pour into the avenue. It must have been about 1:30 p.m.

At the same time, General Lucas Rincon, the Chavista hardliner who was the highest ranking officer in the armed forces, went on a cadena nacional to dispel rumors that Chávez had resigned, and to reaffirm the Armed Forces’ commitment to the government. Rincon gave his speech with a mobile phone clutched to his ear the entire time, giving the none-too-subtle impression that his words were being dictated to him in real time.

We left the tasca started to walk along with the marchers, trying to get some shots of what we could all sense would be a historic day. Marching down the street, I kept reassuring the crew: ‘It’s ok, they had three hours to prepare. Obviously we’ll run into a Guardia Nacional roadblock at the end of the Avenida.’

I didn’t know it at the time, but they actually had 12 hours to prepare, not three. Still, the end of the avenida came: no roadblock.

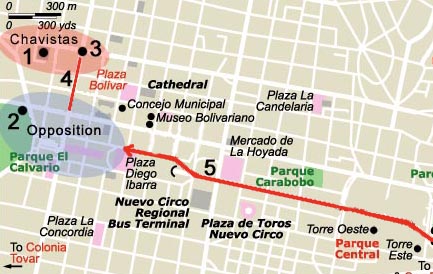

Downtown Detail:

1-Miraflores Palace

2-Calvario Stairs

3-Llaguno Bridge

4-Avenida Baralt: Main shooting alley

5-Avenida Bolivar: Main march approach.

‘Don’t worry, the government can’t be this stupid, obviously there’ll be a roadblock on the next block.’ But no: we kept on walking the remaining six or seven blocks to Miraflores, and to my consternation realized there would be no Guardia barricade at all, just a bunch of heavily armed chavistas waiting for us on the other side.

Finally, just one lousy block south from the palace, a very thin line of Metropolitan Police officers (i.e. people commanded by the opposition mayor of Caracas) stood trying to keep the opposition crowd at bay. They had no riot gear, no gas masks, nothing. The most radical of the opposition marchers simply walked right past them, through a no-man’s-land just one block deep, to the other side, where a similarly thin line of Guardias Nacionales stood, trying in turn to keep the pro-Chávez demonstrators away from the opposition, relying mostly on tear gas.

The next hour is a blur of street skirmishes, tear gas, and any number of explosions that sounded like fireworks but could well have been gunshots. I, for one, can’t tell the difference. The thin line of Guardias had enough tear gas on hand to keep the two sides more or less apart for a while, but opposition hot-heads kept charging them. The atmosphere was impossibly tense, and soon, it became clear to me that this would not end without significant violence.

April 11th March: One block south of Miraflores

By 3:30 we retreated from the Calvario stairs towards Avenida Baralt. Jumpy as hell, I kept trying to persuade Megan to just get the hell out of there – whatever footage we might get out of the melee didn’t seem worth the ration of lead that would come with it. After we got some shots on Avenida Baralt – with the chavistas on Llaguno Bridge clearly visible – a man walked up to us. Megan swung the camera to film him. He put his hand over the lens and said, “No, you can’t film me. I just came to tell you that you should get out of here. You’ll be picked off in particular because of the camera. Get out, now.”

So we did. We didn’t get a single recognizable shot of the guy, so I have no way to know who he was. An infiltrated DISIP suddenly gripped with a spasm of conscience? A guardian angel? I have no idea. I do know that five photographers and cameramen were wounded that day, and one of them, Jorge Tortoza, was killed. For all I know, that guy saved Megan’s life.

We started walking, in the mass of confusion, first south and then back towards the east side. At that time – 4:00 or so – a huge opposition crowd was still walking west on Avenida Mexico, towards the palace. The streets were filled with people, rumors and confusion. For a while, the marchers chanted, simply, “Ejercito cagon! Ejercito cagon!” – the Army is chickenshit, as a way to urge the officers to join the protests in defiance of Chávez.

About 5 minutes after leaving Avenida Baralt, I turned on my pocket radio to scan for news. To my astonishment, what I heard was Chávez’s voice. Incredibly, he had called yet another cadena nacional – a simultaneous live broadcast that all TV channels and radio stations.

The first news blackout of the weekend was on.

I didn’t know it at the time, but the cadena started only minutes after the start of the shootout that left 20 dead and over 100 injured – most of them on Avenida Baralt, the street I’d been standing on five minutes earlier. Because there were so many loud bangs in the air, people did not initially realize that shooting had started. Many of the first to be wounded figured they had been hit with a rock or a bottle: only gradually did people realize that live shooting had started.

The sequence of those first few minutes after the cadena started is particularly confused. It appears that a set of Policia Metropolitana (opposition-led) anti-riot vehicles charged up Avenida Baralt. The chavistas claim the cops shot first, the cops claim the opposite. One way or another, a big firefight started between the two. According to many, there were also sharpshooters spreading bullets from various building tops, though none were ever photographed or identified.

Today, we know that there were deaths on both sides. Because no proper investigation has ever been held, it is not possible to know exactly who started shooting, why and when exactly. We do know that, via the cadena, the government had taken a decisive step to block reporting of the shooting taking place just feet from the palace.

Since I had a radio instead of a TV, I did not see what millions of Venezuelans saw. Enraged at Chávez’s decision to give a rambling speech in the middle of a national emergency, the private TV stations split their screens down the middle. On one side you saw the president speaking, while on the other side you saw live video images of the shooting spree taking place just meters away.

For more than two long hours during perhaps the worst episode of political violence in Venezuela since the 60s, Chávez continued to speak while people died outside. He never stopped to try to do something to stop the shooting. Every few minutes, an army officer would enter the frame and slip the president a bit of paper containing a casualty tally, which Chávez would read, and then continue talking in his most natural voice. He never stopped to do something to stop the violence raging just outside his door.

Not all the shooting that day happened on Avenida Baralt. Both pro- and anti-government protesters died at several other locations in the vicinity. Minutes after the start of the shooting on Avenida Baralt, one man was killed standing directly behind Miraflores, in the Chavista march on Avenida Urdaneta – well away from line-of-sight from the Hotel Eden and the opposition march. The shots, according to police investigations, came from the Bolero building.

Also, the Guardia Nacional troops that had been keeping the opposition marchers away from Miraflores eventually ran out of tear gas and started shooting live rounds into the crowd.

One of the most puzzling subplots here concerns the arrests made by the police at the Hotel Ausonia on the 11th, where several foreigners were arrested with guns and a small quantity of drugs. They jailed until April 16th, and then released unconditionally by a court under the restored Chávez government. They immediately vanished. Who were they? The government has hinted they were opposition sharpshooters, but forensic tests did not show they had fired weapons recently. They were never questioned or arrested after the 16th, and may well have been ordinary criminals who chose the wrong hotel at the wrong time. But who can be sure?

Chávez’s speech continued through 5:30 pm. Towards the end, he announced he was shutting down the country’s main TV stations in response to their conspiratorial actions against him. Little did he know that by the time that decision was made, it was too late for a cover-up: the private TV channels had already split their screens and broadcast live images of the massacre, so everyone in the country more or less knew what was happening.

The next few hours were a time of utter confusion. In Caracas, the terrestrial TV towers were taken over by the Guardia Nacional. However, the private broadcasters remained on the air in the rest of the country, and in Caracas via satellite. Like a lot of other people in town I made my way to the house of my nearest satellite-dish-owning relative (in my case, my sister Ana.) We sat there astonished watching the news coverage of the violence. It was the first time in our lives we had seen people killed in large numbers for political reasons. The sense of crisis grew minute by minute.

By 10:00 pm, Chávez’s former number-2 man, Luis Miquilena, went on television to openly denounce the government’s power play. Given his large following in congress and the supreme tribunal – since he had been given primary responsibility for selecting pro-Chávez officers to those posts – Miquilena’s desertion opened the door, in the eyes of many, to the possibility of a constitutional solution to the crisis. Within hours of his “cadena”, Chávez’s congressional majority had vanished.

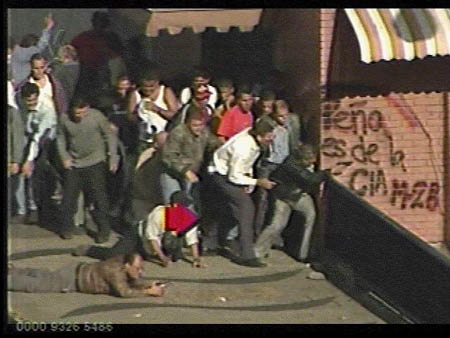

Then came the coup de grace. A Venevision camera crew managed, through an outstanding bit of bravado, to get actual images of some government supporters shooting down into Avenida Baralt from Llaguno Bridge (this “bridge” is really an overpass that crosses over Avenida Baralt.) The images were the only direct evidence of people shooting available that night. In the atmosphere of sheer confusion, it was not immediately evident that anyone was shooting in the other direction. The private TV stations repeated the footage again, and again and again, giving the impression that the opposition march had been ambushed by government supporters.

Images of Llaguno Gunmen shooting south towards Avenida Baralt captured by Venevision. The man in the white jacket is Richard Peñalver.

One of the gunmen was identified as Richard Peñalver, a pro-Chávez municipal council member in the district where I lived – in fact, an elected official. The footage showed him emptying his gun with glee towards the south of the bridge, the area where the opposition march had spent much of the afternoon. At the time, the footage seemed incredibly damning, and whatever support Chávez still enjoyed within the armed forces quickly crumbled.

Now, viewers of The Revolution will not be Televised know that as far as chavistas are concerned, the footage of Puente Llaguno was a blatant manipulation. Amateur video taken from a different angle and made public later showed no protesters on the southern part of Avenida Baralt while the chavistas fired.

The argument, presented as definitive on the film, is hardly enlightening. The film suggests, but does not quite say, that the opposition march had not yet reached Avenida Baralt at that point. It entirely glosses over the question of who shot the civilian marchers who were killed or wounded on the southern part of the avenue. Though witness statements suggest the Llaguno Gunmen only got their guns after the shooting had started, and were filmed shooting well into the gun battle, while the opposition marchers who died appear to have fallen in the first few minutes of the shootout, one must regard their official excuse – that it’s okay because they were shooting at the opposition-led Metropolitan Police – as borderline nonsensical.

Then there was the confusing episode of the tank column filmed going from Fuerte Tiuna through the highway towards Miraflores Palace. If you saw The Revolution will not be Televised you’ll recognize the scene, but you may be surprised to find out that contrary to the spin put on it by the film, the tank movements were not part of the coup. In fact, they were ordered by Chávez. The Ayala Tank Battalion was among the last to stay loyal to Chávez that evening, and they answered his call to surround the palace with military armor.

But by the time the tanks reached Miraflores the vast bulk of the army had risen up against Chávez, and there were reportedly even threats to bomb the palace from the air, Allende style. Of course, if you’re facing an F16 strike, a tank on the street is about as useful as an ashtray on a motorcycle, so the tanks really played no role. On advice from Havana, and owing no doubt also to his own psychological disposition, Chávez rejected the offer of martyrdom and gave himself up, showing up at Fuerte Tiuna wearing (illegally) his military field uniform.

An evening in Fuerte Tiuna

At midday and through the afternoon, Rosendo and Vásquez Velasco had planned to go to Miraflores and tender their resignations to Chávez, explaining why they could not implement his orders in accordance to international human rights law – nothing more. But as the evening wore on, more and more active duty military officers came forward to withdraw their support for the government and demand Chávez’s resignation. The small conspiratorial cliques that had formed between military friends all burst into the open at once.

A reporter friend of mine actually went to Fuerte Tiuna that night to witness the toppling of a government as it happened. There was so much confusion at the fort that he was simply allowed to slip in and mingle with the assembling generals. The story he tells is one of sheer confusion, with a bewildering array of generals milling around trying to decide what to do, while opposition civilians hung around different cubicles drafting God knows what on the PCs they could find. Chief among them: opposition “leading light” Allan Brewer Carias, together of course with Pedro Carmona and others, including even Orlando Urdaneta, a popular, though far-right wing, actor and comedian.

By the middle of the evening, the private TV broadcasters were back on the air in Caracas, and the state-run TV channel had been abandoned by its chavista managers, who feared retribution. (Amusingly, if you tuned in to Channel 8 that evening, you were faced with 30 year old nature documentaries about little ducklings…the last tape hastily thrown on the air as the managers ran.) As it became clearer and clearer that the government was in the process of falling, the Chávez regime started to “melt away.” Any number of pro-Chávez officials and political activists went into hiding.

A confused set of negotiations ensued between Chávez and a now openly rebellious army. Faxes were exchanged, Chávez was initially offered safe passage to Cuba only to later see that offer reversed. By 3 a.m., Chávez had decided to give himself up, and go to the army’s main installation in Caracas, Fuerte Tiuna, to be told his fate.

The negotiations at Fuerte Tiuna on night from April 11th to the 12th were complex, chaotic and confusing. By most accounts, Chávez agreed in principle to resign if he was guaranteed safe passage for himself and his entire family to Cuba. But splits between the rebellious officers were evident: one group, the pragmatists, wanted to just send him off into exile and start afresh. A second group, the maximalists, argued that Chávez should be tried in Venezuela for the afternoon?s deaths and that, in any case, he could become a deeply destabilizing figure if allowed to flee to Cuba.

The military chain of command had gone all to hell, and the evening became a kind of civic-military free for all. Though nominally still in charge, Vásquez Velasco had lost control of the coup.

At around 2:40 a.m. on what was already April 12th, much of the nation was still glued to the TV coverage of the crisis. Suddenly, one last cadena: General Lucas Rincon, the highest ranking member of the armed forces and a chavista loyal enough to have earned a third sun (equivalent to five stars in the US) despite never having fought a war, comes on the screen. He’s flanked by what remains of the pro-Chávez high command of the Armed Forces.

Rincon read a prepared statement. Using an oddly circumloquitous formulation in the passive tense that left it unclear exactly who had done the asking, Rincon announced that President Chávez had been asked to resign, a request “which he accepted.” (“La cual acepto…” was the soon infamous formulation.) Rincon proceeded to tender his resignation together with that of the other pro-Chávez generals, leaving the change-of-president an apparently done deal. Celebrations rang out through the east of Caracas. According to his later congressional testimony, Rincon then went to sleep.

Lucas Rincon: “La cual, acecto.”

(Bafflingly, Rincon remained a member of Chávez’s inner circle for years, after having announced the collapse of the regime to the entire country.)

By dawn, the best organized of the conspiratorial cliques managed to wrest control of the situation. Financed by a shadowy arms dealer by the name of Isaac Perez Recao, the group included General Enrique Medina Gomez – at the time Venezuela’s military attache in Washington DC, Allan Brewer Carias, Daniel Romero (the far-right wing “solicitor-general-for-a-day” who supposedly drafted Carmona’s executive decree), Carmona, the top brass of the navy, and in particular Fedecamaras, the traditionally conservative National Chamber of Commerce. Due largely to their long standing contacts with the late Cardinal Ignacio Velazco – then the influential head of the Catholic Church in Venezuela – they persuaded Vásquez Velasco to accept Pedro Carmona, head of Fedecamaras – as an interim president. Vásquez Velasco, eager to put the country back in civilian hands as soon as possible, accepted.

In the weeks following those events, this takeover by the rightwing conspirators came to be known as the ‘coup-within-a-coup’, and to my mind this remains the best way to describe what actually took place.

Who exactly controlled this group has been a subject of heated controversy ever since. Though Perez Recao took most of the blame, some well informed sources are sure General Medina Gomez was the real boss. Certainly, Medina Gomez flew back from Washington to Caracas just days before the coup – a sign, to some, that the conspirators knew a day of reckoning was coming and they were working to put all their pieces in place before a showdown.

April 12th: The Carmonada

The day after the coup most people woke up to hear that Pedro Carmona would be the new president and he would make a statement later on his course of action. Carmona had been one of the most prominent leaders in the anti-Chávez movement, so his appointment seemed almost natural to many. That morning, the private media refused to ask the evident question: who had chosen Carmona? and by what authority?

Pedro Carmona flanked by Vice-admiral Carlos Molina Tamayo and Army Colonel Gustavo Diaz Vivas, Carmona’s personal guard (edec?n)

That same morning, the White House Press Secretary made a shocking pronouncement that has been used again and again to paint the Bush administration as co-conspirators of Perez Recao, Carmona and company.

As reported by CNN:

“Chávez supporters, on orders, fired on unarmed, peaceful demonstrators,” White House press secretary Ari Fleischer said, referring to Thursday’s violence that killed 12 people and wounded dozens more. “Venezuelan military and police refused to fire … and refused to support the government’s role in human rights violations.” Two things to notice. First off, Fleischer’s statement does leave out half the story. It wasn’t only chavistas firing, but at that point in time, there was no way to find out who else had been firing in the mayhem. Nor could Fleischer be sure that the Chavistas were firing on those they appeared to be firing on. The second part of the statement is perfectly factually correct, though, and of course always conveniently left out of Bushwhacking accounts of the coup.

The second thing to notice is that Fleischer’s main blunder was to speak prematurely. The White House statement was made several hours before Carmona’s provisional government decree had been made public. The statement did not explicitly recognize the new government, largely because the new government had not yet been established.

Though it was retroactively read as a statement of support for Carmona’s government, the White House statement preceded the Carmona decree. In fact, according to sources in Miraflores that day, the Carmona Decree hadn’t even been finalized at the time Fleischer spoke. Ari jumped the gun. By speaking out of turn, he wrote a kind of blank check of US support for whatever Carmona might choose to do – a trust Carmona clearly didn’t deserve.

Verbena en Miraflores

Back in Miraflores, the scene remained chaotic. On the one hand, dozens of job-hunting opposition politicians had turned up for a chance at the spoils. At the same time intense efforts were taking place behind the scenes to get Carmona to reconsider.

While chavista propagandists have associated the coupsters with far right wing figures associated with hyper-conservative catholic groups like Opus Dei, the truth is somewhat more slippery. Though one prominent Opus member, Pepe Rodriguez Iturbe, was named foreign ministers, other Opus-associated figures like Gustavo Linares Benzo were working to prevent Carmona’s power play. In fact, Linares Benzo spent the day lobbying against Carmona’s plans. He proposed a plan to ask the National Assembly to convene and, with Miquilenista votes, certify the “permanent absence” of the president from his post, paving the way to a constitutional transition. Linares Benzo’s proposals garnered some support from the assembled, but Carmona doesn’t seem to have seriously considered them.

Other political figures showed their mettle that day. Cecilia Sosa, the head of the adeca encopetada faction and former Chief Magistrate of the old pre-Chávez Supreme Court, is often seen as a bit of a right-wing extremist. That day, however, she had the law firmly in mind. Sosa faced Carmona down personally just minutes before he read out his decree, explaining to him bluntly that there was no imaginable legal basis for handing him the presidency. “That has already been decided, Dr. Sosa, that has already been decided,” is the only response she got from him.

Cecilia Sosa

The decree eventually drafted and read by Daniel Romero dripped with excesses. At one pen-stroke, on authority granted to them by God only knows who, the decree shut down all the federal institutions, the Supreme Tribunal, the National Assembly, all of them. It suspended 49 Chávez-imposed laws and even changed the official name of the country back to the pre-Chávez “Republica de Venezuela.” In return, the decree pledged elections that Carmona would not participate in within one year. In the interim there would be a kind of legal void, with no elected institutions operating at the national level and nearly limitless power put in the hands of the interim president and an appointed “consultative board.” Carmona then went on to swear himself in as “interim president” swearing to pave the way to the restoration of the validity of the constitution – which is very different from pledging to obey it.

The antichavistas assembled in Miraflores that day cheered the decree wildly, intoxicated with the sense of victory. But the roster of signators who sought to legitimize the decree was worrying. Most signators were hard-right, business-class types. When the announcer called for “the representative of the Workers’ Federation to come forward,” no one turned up…and for good reason. Alfredo Ramos, the only CTV member in the room, later explained that he refuses, on principle, to sign any document he hasn’t read carefully beforehand.

Trouble

As Carmona signed his decree, Carlos Ortega, the head of the Venezuelan Workers’ Federation, was 300 kilometers west in his home state of Falcon. Though Ortega and Carmona had acted as a team in leading the protest movement until April 11th, Carmona had distanced himself in the final 48 hours. By leaving, Ortega wanted to make it perfectly clear that he had no part in putting together the transitional government. This breakdown in the CTV-Fedecamaras alliance, at the most sensitive moment, may have been enough to doom the coup. So long as the anti-Chávez alliance could claim to speak for both employers and workers, it could plausibly represent the whole nation. With labor out of the equation, the movement was reduced to a right-wing power play.

Nor was the situation much better in the barracks. When General Vásquez Velasco agreed to make Carmona president, he had naturally expected to earn the Defense Ministry in return. Instead, Carmona stunned the military by naming a navy man as defense minister. Vice-admiral Hector Ramirez Perez was close to Carmona, Molina Tamayo and Perez Recao, but it was doubtful whether a navy officer could really establish control of the army at such a delicate time. To his shock, Vásquez Velasco heard a rumor that Carmona was planning to send him out of the country, to serve as the military attache in the Venezuelan Embassy in Madrid.

Perhaps because he was a navy man, Ramirez Perez neglected some of the most basic elements of effective coupsterism. Inexplicably, he made no effort to ensure loyal anti-Chávez troops took control of the presidential palace. The pro-Chávez Presidential Guard of Honor regiment was left in place and in military control of Miraflores even as Carmona and his people moved in.

Moreover, the new regime had not shown itself overly concerned with calming the calls for revenge coming from some in the opposition side. The entire leadership of the Chavista government went underground, and a kind of witch-hunt broke down to find them, along with the shooters seen in the previous night’s endlessly repeated video.

At some point, a rumor started making the rounds that Chávez’s vicepresident, Diosdado Cabello, had sought asylum at the Cuban embassy in Chuao. An angry mob was soon on the scene demanding his scalp. The rumor was not true, but the crowd was belligerent, so the Cuban Ambassador, German Sanchez Otero, called the opposition mayor of the area, Henrique Capriles, to come and save his skin. This Capriles did, as best he could, in a highly emotionally charged atmosphere. At the time, Sanchez Otero thanked him. Later, the government persecuted Capriles for “leading the riots” outside the Cuban embassy that day.

Similarly, the Primero Justicia mayor of Chacao, Leopoldo Lopez, had tried to protect then Chávez interior minister Ramon Rodriguez Chacin, who was arrested at an east side apartment. An angry mob had gathered to witness the event: many tried to get punches in to Rodriguez Chacin as he was escorted into police vehicles. The footage was shown repeatedly on opposition news stations that day.

Other chavistas, like self-described Human Rights activist Tarek William Saab, were also arrested that day. In a show of democratic fortitude, a selected few anti-Chávez activists spent the day pleading with the Carmona authorities to release them. Teodoro Petkoff, Milagros Socorro and Ruth Capriles in particular need to be singled out for praise. It would have been far easier and more comfortable for them to look the other way that day. In fact, faced with recent political jailings, chavistas like Tarek himself have shown just how much easier it is to look the other way than to denounce injustices your own side perpetrates.

By the evening of April 12th, the coup was just starting to unravel. General Vásquez Velasco, stunned by the sweeping illegality of Carmona’s regime, started to say out loud that in refusing Chávez’s order the day before, he had intended to protect the constitution, not to establish a de facto regime. CTV continued to stay well away from Miraflores and rumors started to circulate more and more insistently that Chávez had not, in fact, resigned, and that no signed resignation letter existed.

By that evening, the US embassy was fully aware of what a blunder Fleischer’s statement had been that morning. US Ambassador Charles Shapiro reportedly called Carmona to urge him to think again, particularly on the very sensitive matter of dissolving the elected popular assembly. This is another key detail that’s normally suppressed from standard the-US-did-it versions of the story. How you interpret this fact depends on your general attitude to US foreign policy, I suppose. But to me, if the Assembly had certified Chávez’s absence, it would be hard to call what had happened a coup – so Shapiro’s call was, to my mind, an attempt to avert an illegal handover of power, to keep the process within constitutional bounds.

Pedro Carmona rejected Ambassador Shapiro, saying he could not be seen to backtrack on his first major decision. The following day, a desperately isolated Carmona would offer to reverse this position, agreeing to convene the National Assembly after all. By then, it was too late.

Carmona’s biggest problem, though, was that he failed to obtain the one thing he needed to give his rule any semblance of legitimacy: a signed resignation letter. As the hours passed, and especially in pro-Chávez circles, rumors grew that Chávez had refused to sign a resignation letter and had therefore been kidnapped. It was the international media that carried this story first, in particular CNN, which even had a telephone interview from someone claiming to be Marisabel, Chávez’s wife, denying her husband had resigned.

Had the Carmona clique worked to gain a broader base of support, had it not alienated so many potential allies so quickly, it might well have weathered this “bump in the road.” But by the time Carmona realized he had to give way, it was already too late.

April 13th: The Incredible Collapsing Coup

I woke up on the morning of April 13th to a puzzling anomaly. My clock radio woke me up to a nice spot about the history of the arepa. Since I was looking for news, I fiddled with the dial a bit – This Week in Baseball, dubbed, was on one station, a catholic mass on another, and so on. I turned on the TV and found I had a choice between animaniacs, a Major League Baseball game on channel 10, or canned day-old news on Globovision. Hmmm. “That’s it then,” I thought, “just 48 hours old and the coup’s already stopped making headlines…” Politics, I mused, would be commendably boring under Carmona. At last.

But then the phone rang. It was my colleague Juana. “Chamo, I don’t like the way this is going down. The witch-hunt is still going on and suddenly there are no news…who knows what’s happening behind the scenes?! No chamo, I don’t like it at all…” Juana’s call was my first intimation that the coup was in trouble. I started flipping through the radio dial more aggressively. Absolutely no news on any station. “What the hell?” I thought. I had no way to know then that the infamous April 13th news blackout was on.

By late on the 12th, insiders could tell what the rest of the country could not: Carmona’s de facto regime was in trouble. Word that Chávez had not, in fact, signed a resignation letter was spreading fast. Meanwhile, Carmona’s parallel pissing-off of the Labor unions and much of the Army hierarchy was making it increasingly difficult for him to control the situation. Only the media, it seemed, remained solidly in the Carmonista camp.

It appears that on the afternoon of the 12th, Carmona had gathered together the nation’s media owners and asked them, somewhat circomloquitously, to help ensure his government’s stability. The owners understood the coded message clearly enough. Soon, all reporting of the collapsing coup was banned from the private media. During one of the most historically important dates in Venezuela’s contemporary history, the TV channels and radio stations simply ignored the story – with the single, heroic exception of Radio Fe y Alegria, the Jesuit station, and the only station in Caracas to have broken the cartel that day. The media owners were willing to do whatever it took to keep Chávez out of power – and believed, no doubt rightly, that their traditional influence over governance would be restored in a Carmona regime. In this aspect, if in few others, The Revolution will not be Televised actually gets the story right: in an important sense, the media elite owned the coup – and they showed themselves willing to abdicate their duty to inform in order to help sustain it.

Media owners would later claim that conditions were simply not safe enough to send their reporters out that day. As an excuse, it’s not a very good one. Reporters are, by nature, aggressively curious people. Many were dying for permission to go out and report on the events of the day. Their bosses told them in no uncertain terms they could not. Some went out anyway, some even going as far as to sneak into Miraflores Palace to cover Chávez’s return against their editors’ objections. In some cases, those editors refused to run the stories that resulted.

Surely, the streets were dangerous that day, but it was hardly Beirut. There was rioting and looting in much of the city, especially in the far west, Petare and Chapellin. There were reports of Metropolitan Police excesses in trying to quell these disturbances, and I’ve heard stories of up to 50 looters shot dead, though – to repeat my mantra once again, it’s impossible to be sure because no serious investigation has ever been held. The absence of news about the latest crises gave the situation a strange, other-worldly feel. To see your city burn is one thing. To see it burn and to see the media refuse to talk about it is quite another. The rumor mill went into unprecedented overdrive.

I was lucky that day. Since I was working as a freelancer, there was no boss around to stop me from going out and reporting. So I did. I’d heard rumors that Chavistas were congregating outside Fuerte Tiuna to demand the president’s return. At about 11:30 am, Megan and I headed out with a video camera to see if we could talk to them. We somehow managed to find a taxi driver crazy enough to take us there, and we headed out.

First, we drove through downtown. The city was mostly deserted. Very few cars, almost no pedestrians, and little groups of 5-15 chavistas on most corners holding pro-Chávez signs. Our cab driver radioed her colleagues to find out the situation in Catia, and quickly refused to take us there. “Too much shooting,” she said. She agreed, however, to take us to Fuerte Tiuna.

As we crossed the tunnels on the way to the Fort, we got an up-close look at some of the west-side shantytowns. We saw the same thing we’d seen downtown. Small groups of people, in clumps of 5 or 10 or 15 at most, had come together on some corners to wave Venezuelan flags and hand made signs demanding Chávez’s return to power. Some cars honked at them in support.

Arriving at Fuerte Tiuna’s main entrance was a bizarre experience. A set of three armored personnel carriers blocked the entrance, and a line of military police was deployed just in front of them. Behind the soldiers, there was a small but exceedingly emotional pro-Chávez crowd covering the highway overpass into Fuerte Tiuna. The crowd did not quite fill the overpass – to my untrained eye it looked to be about 1000 people or so.

They were, however, about as angry as I’ve ever seen anyone be angry. They were enraged at the blackout, and grateful for the chance to explain what was happening to a camera. “We’ve been coming since yesterday. Yesterday the Metropolitan Police came in to disperse us shooting. They left a whole bunch of people dead. But we’re back now because Chávez is our president and we know he’s being held hostage and we demand him back!” said one woman, tears rolling down her face.

We spent about an hour on that overpass, getting footage and talking to people. The atmosphere was tense and emotional – the soldiers really looked like they had no clue what they were doing there – but everyone was really nice to us. At about 1:30 we took a taxi back home. On the way, I scanned the radio for news again. Nothing.

Meltdown

By this time, the coup was crumbling fast. Most relevantly, General Vásquez Velasco had decided to strike back against the Carmona faction. In mid-afternoon he went on the air to read a communique. I think it’s worth quoting it at length, because it really is quite an extraordinary document:

“On April 11th, the Army issued an institutional statement with relation to the casualties generated that day due to the unwillingness to dialogue on the part of the President of the Republic and his government. Civil society, rich and poor together, marched peacefully and were repressed by the forces of order and attacked by sharpshooters around Miraflores Palace.

“The army was ordered to place tanks on the streets, without the consent of the Commander of the Army (i.e. Vásquez Velasco himself.) This could not be tolerated, because it would have caused thousands of deaths. Our statement on April 11th was institutional and geared against the actions of the government. It was loyal to constitutional norms and consistent with democratic institution. It was not a military coup perpetrated by the army.

“As Commander of the Army, together with the high command and many other officers, we send a message of calm to the people of Venezuela and we inform them that the army is working hard to correct errors and omissions made in this transition. We therefore make the following demands:

1. Establish a transition based on the 1999 constitution, the applicable laws, and respect for human rights.

2. Eliminate the Transitional Government decree of April 12th, 2002.

3. Reconvene the National Assembly.

4. Seek consensus with all the social forces in the nation to constitute a transition government that is representative and marked by pluralism.

“We issue a call to peace and calm, and for every government action to be carried out with maximum respect for human rights…

“We demand the construction of a society without exclusion, where any protest or disquiet can be manifested peacefully, without weapons, and with the full exercise of liberty within the rule of law…

“We guarantee the security and the respectful treatment of Lieutenant Colonel Hugo Chávez and his family. We urge the authorities to comply with Lieutenant Colonel Chávez request to leave the country immediately and we demand live TV images of Lieutenant Colonel Chávez be broadcast immediately.

“We the members of the Armed Forces guarantee the security of all the people of Venezuela.

Mayor General Efrain Vásquez Velasco

Commander of the Venezuelan Army

Some fascist he is, huh?

Several things to note about the statement. First of all, it makes a mockery of those who would equate April 11th, 2002 with September 11th, 1973 in Santiago. One struggles to picture General Pinochet signing a declaration like this one. More clearly than any other document from that weekend, the statement makes it clear that, whatever April 11th-14th was, it was not a traditional Latin American coup d’etat.

The other thing to notice was that, in some ways, the statement is the public start of the counter-coup. In many ways, General Vásquez Velasco made both the key decision in toppling Chávez and the key decision in reinstating him.

Hearing the statement, Carmona finally realized his decree was untenable. He went on National Television late in the afternoon to pledge to reverse course and, in particular, convene the National Assembly – which had become the key litmus test of respect of the constitution. By that point, it was way too late. The plan to bring Chávez back was already well underway.

The counter-coup

Sensing that the coup was faltering, two key pro-Chávez army officers stepped forward, General Jorge Garcia Carneiro and General Raul Baduel. Together, they put together an “Operation Restore Dignity” – to return Chávez to Miraflores. No one dared to fight them on this.

Garcia Carneiro was, at the time, head of the army division based in Fuerte Tiuna. He never acquiesced to the coup, though some claim he chickened out badly at one point. Story has it that on the 13th, Garcia Carneiro managed to get out of Fuerte Tiuna in a light tank which he drove through the west-side slums urging people to rise up and restore Chávez. Garcia Carneiro has since been given his “third sun” and, despite a mediocre military record, he’s now Defense Minister.

The second and far more influential player was Baduel, the head of the Paratroop Brigade based in Maracay, about 150 kilometers west of Caracas. Baduel, who has since been promoted to Vásquez Velasco’s old job as overall Commander of the Army, is an old friend of Chávez. In April 2002, he commanded the brigade Chávez once belonged to. Journalists who have made it into his office are always amazed by the smell of incense and the eastern religious paraphernalia he keeps around. Baduel makes no attempt to hide it: he’s a proud, practicing Daoist.

General Raul Baduel

Baduel had been close to Chávez for many years. He participated in the infamous 1982 Saman de Güere conspiratorial oath, pledging to work together for a revolution. The general soon made it clear he would not cooperate with Carmona’s de facto regime. This is significant because the 43rd Paratrooper Brigade is by far the best equipped and best trained fighting force in the Venezuelan army. By most accounts, the paratroopers are really the only well equipped and properly trained fighting force in the army. Baduel set about coordinating the operation to first locate and then bring back Chávez to Miraflores.

Baduel’s move changed the military equation decisively. The rest of the army quickly understood that, to make the coup stand, they would have to shoot it out with the Paratrooper Brigade, something nobody wanted to do. As Carmona had already alienated most of his natural base of support by then, the rest of the army was loathe to fight and die for him. Baduel’s decision to back Chávez essentially closed the deal.

Carmona never had a chance to react. By the time he realized that the Presidential Honor Guard, the Caracas Army Division and the Paratroopers were all working to bring back Chávez, his support was too narrow to stage any kind of fight back. In the afternoon, a pro-Chávez crowd began to assemble outside Miraflores. Soon enough, Carmona caught on that the Honor Guard would not act to disperse them. In a frightful hurry, he and his people abandoned Miraflores, leaving behind stacks of agendas and documents that the chavistas deeply enjoyed reading over the following weeks. Lists of potential Carmonista ministers left behind in the rush have been used again and again by the government to tar those listed in them.

As the coup collapsed more and more visibly, more and more chavistas felt emboldened to come out onto the streets. By 10:00 p.m. a decent crowd had gathered in front of Miraflores Palace – about four blocks’ worth of Avenida Urdaneta, according to eye-witnesses. Certainly, it’s quite impressive to turn out 30 or 40,000 people with no official organization and in dangerous circumstances like this. The hardest of Caracas’ hardcore chavistas sure did turn out: they were not about to miss the momentous occassion of Chávez’s phoenix like return to power.

But even when the chavistas get it right, they have to go and ruin it with crazy exaggerations. Instead of embracing the 40,000 outside Miraflores that night, Chávez went on to claim that as many as 8 million people had come out on the streets that day. In official chavista lore, it was this massive people-power outburst of solidarity that brought Chávez back to power. Alarmingly, I’ve seen more than one foreign correspondent buy this line, which is demonstrably wrong.

The 8 million figure is not even believable as a send up. Not only is the estimate at least two orders of magnitude too large, but it gets the causality backwards: Chávez did not return because the crowds came out, the crowds came out because they realized Chávez was about to return. The key decisions – both to remove Chávez and to reinstate them – were taken behind closed doors by high-ranking military men.

At about 8:00 pm, the situation turned nastier. Incensed at the absence of news coverage that day, pro-Chávez civilian groups – the famous Circulos Bolivarianos – activated a plan to stick it to the private channels. Riding around in swarms of motorcycles, they started touring the studios of the main TV channels, throwing stones through the windows and shooting into the buildings sporadically. The media switched, within minutes, from showing shlocky American made-for-TV movies to covering what was happening directly outside their doors. For over two hours, they cowered in terror, using the airwaves to ask for someone, anyone to come and protect them. But with Carmona having already lost control of the situation, the military chain of command had collapsed all over again. There seemed to be no one around with the authority or the desire to order the National Guard to step in and stop the violence.

By 10:00 pm or so, word got around that although the Venezuelan channels had no real news, Colombia’s Radio Caracol and CNN en Español had coverage of the crisis. Since Caracol comes through the satellite dish system in Caracas, once again the city was split between the dish-owners, who had access to information, and everyone else. By 11:00, Radio Caracol had made it clear that the coup had comprehensibly unravelled and Chávez was on his way back to Miraflores. The Venezuelan stations only announced as much after midnight. In an interview I’ll never forget, a terrified Pedro Penzini Fleury interviewed hardcore pro-Chávez National Assemblymember Cilia Flores on UnionRadio, and I swear at one point he half-apologized to her for having overthrown her government. Surreal.

By 3:00 a.m. the following morning, the chavistas had retaken Miraflores and symbolically swore-in Chávez’s vice-president, Diosdado Cabello, as head of state. A few hours later, Chávez returned to Miraflores to an ecstatic reception from his followers. Even the most recalcitrant anti-chavista journalists I know who were at Miraflores for the event own up that it was a moving, exciting experience. “That day,” one of them told me, “it doesn’t matter how escualido you thought you were, when you saw the faces on the people outside Miraflores as Chávez got out of that helicopter, you could not help but be a chavista.”

A chastised Chávez gave an early morning speech, thanking his supporters and pledging to change, to really change after this experience. He promised to govern inclusively, to bring critics on board. The good intentions did not last long, but the promises fanned speculation that certain conditions had been imposed on Chávez before he had returned to office, including chiefly a change in tone. Consonant with the conditioned-return theory is the fact that the president has never again been seen illegally wearing his military uniform – a key source of friction within the army.

Taking stock

This is as much as I know about what happened that weekend. Clearly, many questions remain unaswered mostly because – have I mentioned this yet? – no proper investigation has ever been held.

It’s worth dwelling on this a bit longer, because more than anything that happened on April 11th-15th, it’s the government’s subsequent unwillingness to investigate that seems most damning to me. Certainly, they were urged to investigate credibly from the very first day after Chávez’s return. On April 15th, Teodoro Petkoff wrote this in his Simon Boccanegra column:

“The killings on April 11th around Miraflores Palace must not remain a mystery. Those responsible must be taken before the courts. But to find them, an investigation has to be headed by a sort of ‘truth commission,’ an absolutely impartial body trusted by all. In this war of accusations and counter-accusations, it’s the government that stands to gain the most from a Truth Commission because suspicion today falls most strongly on some of its backers. The Prosecutors’ Office must, of course, carry out its duties, but just like in some Central American countries and Argentina and Chile, the official institutions should act in parallel with a Truth Commission in order to clear up any doubt about what happened. No investigation carried out only by official institution, regardless of the evidence they put forward, will be credible. National reconciliation can only be achieved through justice, not revenge. The basis for justice is truth.”

Two days later, he added:

“Everyone understands that only an impartial investigation will be credible to everyone. Turning this page, not allowing this despicable episode to turn into a tumor that attacks the entire future political life of this deeply divided country, will only be possible establishing the truth and prosecuting those responsible for what happened.”

And on April 18th, he wrote:

“What we had feared has started to happen. The sad events of April 11th have already been turned into projectiles tossed back and forth between the various political parties, who accuse each other of responsibility for the deaths. Instead of waiting for the result of an investigation from a Truth Commission, in Parliament each side went straight for “its” videos and “its” photos to sustain “its” truth. This road is totally barren and, from the start, demonstrates an unwillingness to get to the truth. Each side seems to want to keep the affair in a cloud of uncertainty, seeking to keep the events confusing enough to use as a political argument in future debates. This would be a calamity for the country.”

It was only one week after this piece that prosecutors finally moved in to “secure” the crime scene. By then, most of the evidence was gone, obviously.

Writing just a week after the massacre, Teodoro showed why he is the only political analyst in Venezuela today whose judgment one can trust unreservedly. Today, almost two years later, the country has seen neither a Truth Commission nor an impartial investigation. Just as Teodoro predicted, the deaths have turned into an inscrutable mystery, poisoning an already tense political atmosphere. Physical evidence of the crimes on Avenida Baralt was allowed to decay for two weeks before Fiscalia experts showed up to secure it. By then, much of the evidence – bullet cases, broken windows, etc. – had been cleared away.

Meanwhile, the Puente Llaguno gunmen have been repeatedly feted by the president as “heroes of the revolution.” The only people being actively investigated for murder for the events of April 11th are the Metropolitan Policemen who tried to keep the sides apart on Avenida Baralt.

Just as Teodoro predicted just a week after the events, the deaths from April 11th have become a political molotov cocktail, a weapon used by each side to blame the other. In the hands of openly chavista prosecutors like Danilo Anderson, the investigation into the affair is a mockery, a slap in the face for those who were killed and wounded that day. Barely bothering to hide his partiality, Anderson first motioned to move the Llaguno Gunmen trial to Aragua State – a hotbed of judicial chavismo – and, not surprisingly, did not manage to convict any of them of anything. While Richard Pe?alver walks the streets as a revolutionary hero and vows to the press to continue to defend the revolution “with my hands, or whatever I may have in my hands”, Henrique Capriles dodges an arrest warrant for trying to stop a riot outside the Cuban embassy the following day.

By now, it’s doubtful whether the crimes of April 2002 can ever be solved. Barring a spectacular revelation by an insider, it’s hard to imagine how even the best investigator could get to the bottom of this. It’s what the government wanted.

As new cases of political violence are registered in Caracas, the government remains committed to its April Crisis game-plan when facing opposition accusations of violence: first, appoint a politically motivated prosecutor (preferably Anderson), second, wait, third, carry out a flawed investigation, fourth, convict no one. The result has been systematic impunity for anyone who acts in the name of the revolution.

The other purpose of this essay was to clear up what we know about the role of the US in this mess. I believe that US influence was decidedly marginal. The political forces tearing Venezuela’s society (and its military) apart were strong enough to account for what took place. The assertions of US involvement in the coup that I’ve seen are mostly matters of speculation or dogma, and they never seem to be based on a specific hypothesis about what the US did, when, and how. Proving that, several months before, some US-funded organizations had given money to some of the people who were eventually involved in the coup is simply not good enough. And Chavista allegations that US Navy ships operated inside Venezuelan territorial waters hardly clear matters up: if it’s so, what was their role? What were they doing? What, specifically, did the CIA do to aid the coupsters? (or the coupsters-within-a-coup?) What are the mechanics of US involvement?

I’ve never read a plausible answer to those questions. This is not to say the US was not involved, merely that I’ve never seen a good reason to think the gringoes were involved. As a rule, those who allege US involvement seem far more interested in bashing American foreign policy than in understanding the complex events of that weekend. Plan Avila, for instance, is never mentioned, and the cadena-during-a-massacre is always glossed over. In fact, only evidence that tends to suggest US involvement is trotted out, everything else is suppressed. As I noted, the words “Plan Avila” are uniformly suppressed from chavista retellings of the story. This kind of selective forgetting is, to my mind, a distinguishing feature of political propaganda.

Those who want to argue that the US was a key player in the story have a duty to explain to us precisely what it is the US did, when, where and how, and how those actions fit in with the rest of the story as we understand it on the basis of the available evidence. Otherwise, the “Bush-did-it” hypothesis comes to sound entirely contrived – a propaganda slogan based on faith devoid of documentary underpinnings.

To my mind, the bulk of the evidence suggests that the decision to remove Chávez was made by the Venezuelan Army under quite unprecedented circumstances, and the decision to bring Chávez back was also made by the Venezuelan Army under quite unprecedented circumstances. Others are entitled to interpret events differently, but they must do so on the basis of evidence rather than ideological assertion.

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 22 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate