The Petrostate that never went away: Part I

With vague hopes that some curious, open-minded World Social Forum participants might stumble on Caracas Chronicles over the next few weeks, I’m re-posting again this background piece from early 2003 on the history and evolution of the Venezuelan petrostate. It’s a longie but a goodie, this one, a reaction to the context-free way Chavez’s leadership is typically discussed in the first world. I’ve just finished editing it to bring it up to date.

The Petrostate that was and the Petrostate that is:

I: The Accion Democratica Model

Back in 1996, I did some field work for a thesis on the Venezuelan labor movement in Cabimas, a dusty little oil city in on the eastern shore of Lake Maracaibo. One day, I met a bunch of guys playing basketball at a municipal court and thought I’d hang out with them for a while – not that I’m any good at basketball, but I thought they might offer a different perspective on things.

Later, when I told my labor movement buddies what I’d been up to, they were horrified. “What!? You were hanging out with those adeco basketball players? Oh Jesus, did you give them any information?!”

I was shocked. Adeco basketball players? I’d often heard about how deeply political parties had penetrated Venezuelan society, but the notion that even the guys shooting hoops down the street had a party affiliation struck me as deeply weird.

I was shocked. Adeco basketball players? I’d often heard about how deeply political parties had penetrated Venezuelan society, but the notion that even the guys shooting hoops down the street had a party affiliation struck me as deeply weird.

Undaunted, I went back and asked the guys about it.

“So, you guys are from AD?”

They kind of smiled awkwardly and one of them said, “well, we needed a court and…”

He went on to tell me the story about how they’d always wanted a proper court to play on, and they’d never had enough money for shoes, balls and uniforms and such. The mayor of Cabimas at that point was an Accion Democratica politician, and one of their uncles was a party member, so they asked him for help.

The uncle pointed them to their neighborhood AD party official. They went asked him if he’d press their case with the mayor. The organizer said he would, but told them the mayor would be, cough-cough, much more likely to sympathize with their request if they’d sign up to become party members.

The bargain was pretty simple – a chunk of the municipal recreation budget in return for joining AD and helping out with election campaigns and get-out-the-vote drives. This didn’t strike the guys as such a bad deal, so they signed up, pressed their case, and after a year or so they’d gotten their court built, and a few balls to play with…with the slight inconvenience that the whole town started to think of them as “those adeco basketball players.”

I love this little anecdote because it encapsulates so neatly the entire structure of the Venezuelan petrostate, the old-system Chavez built his image denouncing.

The petrostate trick is turning oil money into power – or, more precisely, turning control of the state’s oil money into control of the state – in a self-perpetuating cycle.

The way you do that is by building a huge patronage network. Tammany Hall politics on a national basis.

The party organizer in Cabimas was able to use his influence over a small share of the state’s oil money – just enough to build a basketball court – to fund a miniature local patronage network. His clients – the basketball players – would return the favor on election day, not due to any sort of ideological affinity, but simply to keep their access to his influence over funds. And he would use his influence over them, his ability to mobilize them for political purposes, to bolster his position in his role as client to the next patron up the line, the mayor.

This basic pyramidal system was replicated all throughout the country, in every imaginable sphere of life, from multi-billion dollar infrastructure projects to things as petty as a neighborhood basketball court.

The mayor of Cabimas – who played the role of patron in his relationship with the neighborhood organizer – was in turn client to the next patron up the line, probably the governor of Zulia state. And the Zulia governor played client to his higher up, perhaps a politician or a faction in AD’s all powerful National Executive Committee. And that patron in turn played client to the party secretary general, or to the President of the Republic…one neat string of patron-client relationships running from the dusty backstreets of Cabimas all the way up to the presidential palace in Caracas.

Copei, the second party, ran a parallel (if somewhat smaller) patronage pyramid, and MAS, the nominal left-wing party, ran a much smaller and weaker one.

This, basically, was the system Chavez was elected to dismantle. By the time the 1998 elections came around people resented it acutely. But before launching into a (by now redundant) critique of the system, it bears stopping to notice a few of its features.

For one thing, it’s important to realize that the system was not totally paralyzed – the basketball court did get built. No doubt the funds that built it were mercilessly stripped at every step of the ladder from presidential palace to dusty backstreet as successive layers of patrons took their cut, but the court did eventually get built.

So while it was inefficient, bloated, antidemocratic, and everything else, the system was not totally useless – and in its own amoral way, the corruption served as a rough-and-ready way to spread the oil money around, to make sure its benefits reached many hands, not just a few. The recipients of the final product – the basketball players – were the end-point of a sprawling corruption scheme: it’s just that they got paid off for their services in courts and basketball gear rather than cash.

The Petrostate is a State of Mind

It’s important to note that the Petrostate is not simply a system of social relations – a huge pyramid linking everone who’s on the take – it’s also a cultural system, an interlocking set of beliefs, a state of mind.

The guys in Cabimas had no doubt that if they wanted a basketball court, it was the state’s job to build them one – after all, wasn’t the country awash in oil money? Insofar as the petrostate has a culture, that’s its central conceit – the idea that the government has so much oil money that it can, and should, bankroll the needs and desires of the entire society.

Within the petrostate mental model that’s what the state is for, and governments are to be judged by how well they deliver on that promise.

That’s not just me saying it – polls consistently find that over 90% of Venezuelans think this is a rich country, with over 80% calling it – incongruously – “the richest country on earth.”

Those beliefs didn’t just appear in the popular imagination by accident. The petrostate’s founding myth was at the center of the AD political program from the 1950s onward. AD’s founding father, Romulo Betancourt, wrote a number of books on the subject.

Those beliefs didn’t just appear in the popular imagination by accident. The petrostate’s founding myth was at the center of the AD political program from the 1950s onward. AD’s founding father, Romulo Betancourt, wrote a number of books on the subject.

For a while, it worked. So long as the population was relatively small, the state relatively efficient, and the oil revenue stream relatively steady, a simple redistributive strategy went a long ways.

Throughout the 50s, 60s and into the mid 70s, the petrostate model yielded a huge improvement in Venezuelans’ standards of living. Infrastructure got built, people got jobs, and each generation could reasonably expect to live better than the one before. The country got universal schooling, free universities, hospitals, public housing, sewers, phones, roads, highways, ports, airports, and all kinds of markers of modernity decades before other Latin American countries had them.

Less tangibly, but just as importantly, the petrostate bankrolled institutions ranging from paid maternity leave and severance pay, to old age pensions and statutory vacation pay, all the way back in the 1960s.

By creating sprawling patron-client networks, the political parties became strong enough to make a limited form of democracy viable. The web of social relationships were arguably quite useful in the early decades of democratization. Patronage webs ensured that enough people were socially and economically attached to democratic institutions to feel they had a personal stake in the political system. This loyalty was a key to keeping the country stable and democratic at a time when most of Latin America was not.

And it worked, the system actually worked. There were elections every five years, parties routinely and peacefully alternated in power, Venezuela was an island of democracy and stability in a continent torn apart by Marxist insurgents and coup-plotting generals.

Breakdown

But it didn’t last. There are many reasons why the relatively benign clientelism of the 50s and 60s atrophied into the kleptocratic lunacy of the 80s and 90s. Corruption is the typical reason cited, but the truth is both more complex and less morally satisfying than that. The underlying reason for the system’s breakdown, in my view, has everything to do with the increasing volatility of the world oil market, together with appalling mismanagement and good old demographics.

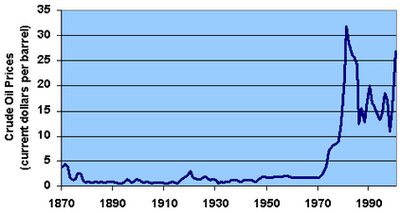

Until 1973, oil had traded in a relatively narrow price range, making Venezuela’s revenues more or less predictable from one year to the next. The petrostate model worked rather nicely under such conditions.

But starting with the oil embargo in 73 – remembered as the “oil crisis” in importing countries but as the “oil bonanza” here – the world market started to gyrate wildly, making it impossible to forecast state revenues with any degree of certainty. With each new boom, huge torrents of petrodollars would pour into the Venezuelan economy, only to be followed by busts that were just as marked and unexpected.

This boom and bust cycle was destructive on a number of counts. From a merely macroeconomic point of view, it’s clear that economies don’t do well under that sort of instability.

More destructive than the market cycle itself, though, was the chronic government mismanagement of the cycle. The politicos seemed to believe that high prices would last forever, and so they would take out huge new debts even as money poured in at record rates. When prices fell, the boom-time excess would only fuel increasingly acute recessions, made all the worse by the new debt burden that had to be financed. This is the famous debt-overhand hypothesis that many careful observers blame for the onset of Venezuela’s economic decline in the 1980s.

But I would argue that the most destructive effects of the petrostate were cultural rather than economic. The massive influx of oil dollars in the 70s shifted public morals in this country. Amidst the abundance of oil dollars, graft became accepted in a way it had never been before. The perception was that only a pendejo, a simpleton, would miss out on the opportunities for easy riches that proliferated in those days for the well-connected. This culture of easy-going racketeering, of matter-of-fact robbery, penetrated deep into the Venezuelan psyche. We’ve never managed to shake it.

At the same time, population growth gradually diluted the oil wealth among a bigger and bigger pool of recipients, making the principle of petrodollar-funded prosperity for all ever less feasible. Even if the state redistributed all its oil rents in cash equally to everyone, most Venezuelans would not stop being poor.

By the late 1980s, the petrostate model had broken down irretrievably. Even if the politicians of the day had been a gaggle of angels gifted with Prussian administrative efficiency, there just wasn’t enough oil money to go around.

Alas, the politicians we had then were the polar opposite of Prussians and anything but angels.

Patrons’ reliance on their patronage networks to sustain their positions made the entire system exceedingly difficult to reform, and particularly deaf to calls for change from the outside. Never particularly suited to ideological debate, the petrostate model became ossified completely: power itself became its only ideology. The drive to amass more of it, to climb higher in the pyramid, to gain access to ever more lucrative sources of patronage, came to dominate the political system entirely. As the system became more and more dysfunctional, people’s resentment of the corruption at the heart of the system grew ever stronger, though very few within the state seemed to recognize it at the time.

So the late 1980s were a critical moment in the country’s history. Venezuela needed massive reform. It needed to reinvent itself, to leave behind a model of governance that was well past its sell-by date and find a way to integrate itself into the world economy, shedding its reliance on oil, not just as a source of money, but as lynchpin of its socio-political and cultural systems. Venezuela needed to ditch clientelism, reinvent social relations at every level, pry apart the patronage networks that had defined its social relations for so long. We needed to ditch the notion that the state could bankroll everyone’s way of life just by distributing the oil money. We needed to invent a whole new idea of the state, a new model where the state helps us create wealth instead of distributing wealth to us. What Venezuela needed was nothing short of a total rethink of society, the state, and the relationship between the two.

And we failed.

That failure is the reason Hugo Chavez is in power today. His political success is the inevitable outcome of our inability to cast off the petrostate model.

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 22 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate