Of Kings and Tyrants

One perk associated with my (otherwise embarrassing) fascination with ancient history is that I get to go on riffs like this:

One perk associated with my (otherwise embarrassing) fascination with ancient history is that I get to go on riffs like this:

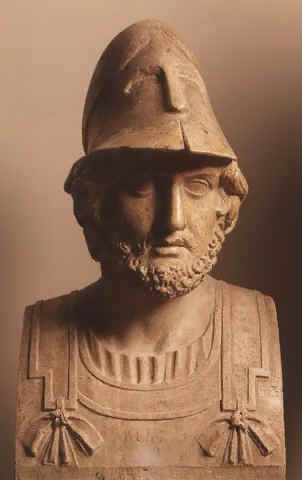

The ancient Greeks made a sharp conceptual distinction between two types of one-man rule: the first, kingship, was legitimate. The second, tyranny, was not. The difference between them didn’t necessarily have that much to do with what political scientists today would call “legitimacy of origin”. In fact, though the more usual route to tyranny was via a coup, some tyrants actually started out their political careers as kings. (Aristotle dixit: “Pheidon at Argos and several others were originally kings, and ended by becoming tyrants”, in Politics, Book 5, Part 10.)

So if a king (a basileus) could become a tyrant, how could you tell the two apart? How could you tell if your legitimate king had crossed the line into tyranny?

The key, it seems, had to do with a single word: responsibility.

Starting out as tribal chiefs, Greek kings were basically “first among equals”. A basileus led the state, but he had an obligation to respond to his peers for his actions. Citizens were entitled to question the king, to be consulted, and to demand reasoned explanations for his conduct of state affairs from him. The king was legally obligated to answer them. They were, in the original, literal sense of the word, responsible: bound to respond, to answers for their decisions.

This, for the greeks, was the key. A king became a tyrant when he stopped observing his duty to answer to his citizens.

And, as Aristotle put it,

Tyrants are always fond of bad men, because they love to be flattered, but no man who has the spirit of a freeman in him will lower himself by flattery; good men love others, or at any rate do not flatter them. Moreover, the bad are useful for bad purposes; ‘nail knocks out nail,’ as the proverb says. It is characteristic of a tyrant to dislike every one who has dignity or independence; he wants to be alone in his glory, but any one who claims a like dignity or asserts his independence encroaches upon his prerogative, and is hated by him as an enemy to his power. Another mark of a tyrant is that he likes foreigners better than citizens, and lives with them and invites them to his table; for the one are enemies, but the Others enter into no rivalry with him.

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 22 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate