Open Data and the Case for a Ni-Ni-Ni 6D

Even today, a plurality of Venezuelans identifies neither as chavistas, nor as maduristas, nor as opposition supporters. They hold the keys to the kingdom.

Llorens and Ron

Last Friday, in Lugar Común bookstore, Altamira, was a chance to ponder on what will happen a week from now, on 6D National Assembly Elections. But it wasn’t about Datanalisis or Hinterlaces predictions, we have enough of those in the newspapers and the internet. The speakers – psychologists Manuel Llorens and Miguel Ron – presented Encuestas Libres, their their open data research project on public opinion, with their own estimations for the elections to come.

Llorens and Ron agree that opposition candidates will win the national popular vote. How large the margin will be depends on how many non-chavista-non-opposition voters will turn out next Sunday.

Normally, public opinion surveys are conducted by private enterprises whose business relies on providing information to paying customers. Sometimes, their partial results are featured on newspapers or websites, but most of their analyses are not meant to be shared with the general public. This group decided to undertake an alternative path, promoting public discussion through open access. The resulting product is encuestaslibres.org.

The main difference between this initiative and traditional political opinion data is their approach: they want to learn something about people’s political identity and opinions from their own points of view. So in addition to two rounds of traditional public opinion polls (national sample of 1000 subjects) they also conducted in-depth interviews following political opinion changes during a period of two years for the same sample.

Innovative, to say the least.

The orange chairs set up inside Lugar Común weren’t enough for the crowd that showed up that evening. You could make out the standing room only crowd from the shop windows on the street. They were all looking at the coffee bar, transformed into a podium where the speakers were talking about their research results. Behind them was an Italian coffee maker and above it, white shelves held anything from white cups with their plates to piles of books. On the top shelf, a video monitor showed the statistical data to the public.

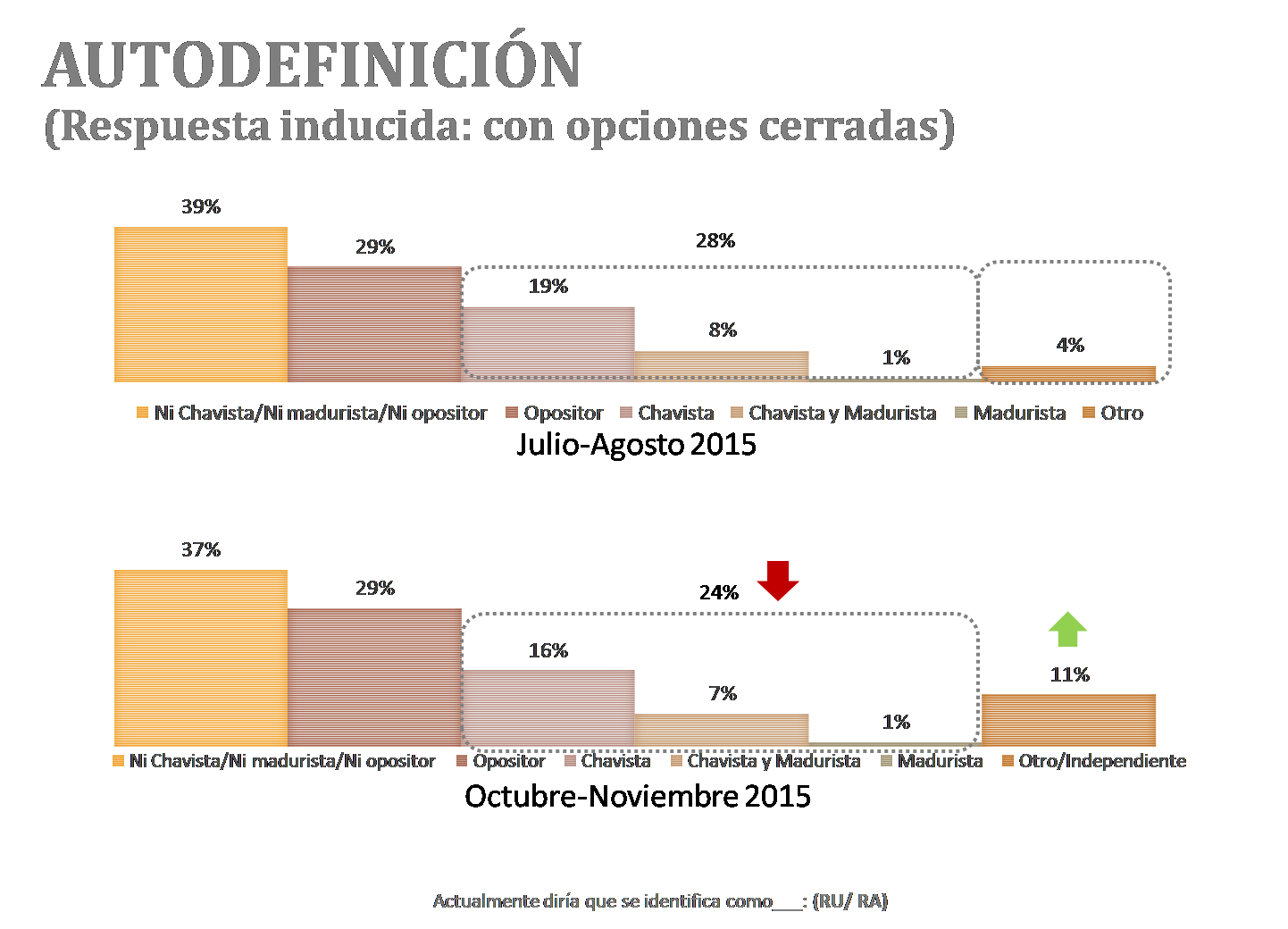

First of all, they showed how the people in the sample who identify themselves and the majority as non-opposition, non-chavista, non madurista (they call them “ni-ni-ni”): 39%. People identified with opposition or chavismo are almost equal, 29% the former and 28% the latter.

They also asked about their past political affiliation and found that most of the chavistas were adecos before and most of the ni-ni-ni were chavistas before. The issue here is how to explain why disillusioned chavistas changed into ni-ni-ni’s or into opposition. When people were asked about their motives, disappointed chavistas became ni-ni-ni because of our difficult economic situation, specifically, food shortages. But once they became aware of existing corruption among their political leaders, they were more likely to identify as opposition.- So hey, MUD: why isn’t corruption a big campaign issue??

Those with a political identification with one of the poles of our polarized election, are the most likely to vote on 6D, more than 80% of chavistas and opposition say they will. But people identified as ni-ni-ni are less determined to vote, and their vote intention diminished between August and November. The majority of this group would vote for opposition candidates because of the economic situation, but government strategy to promote fear and demobilization appears to be successful so far.

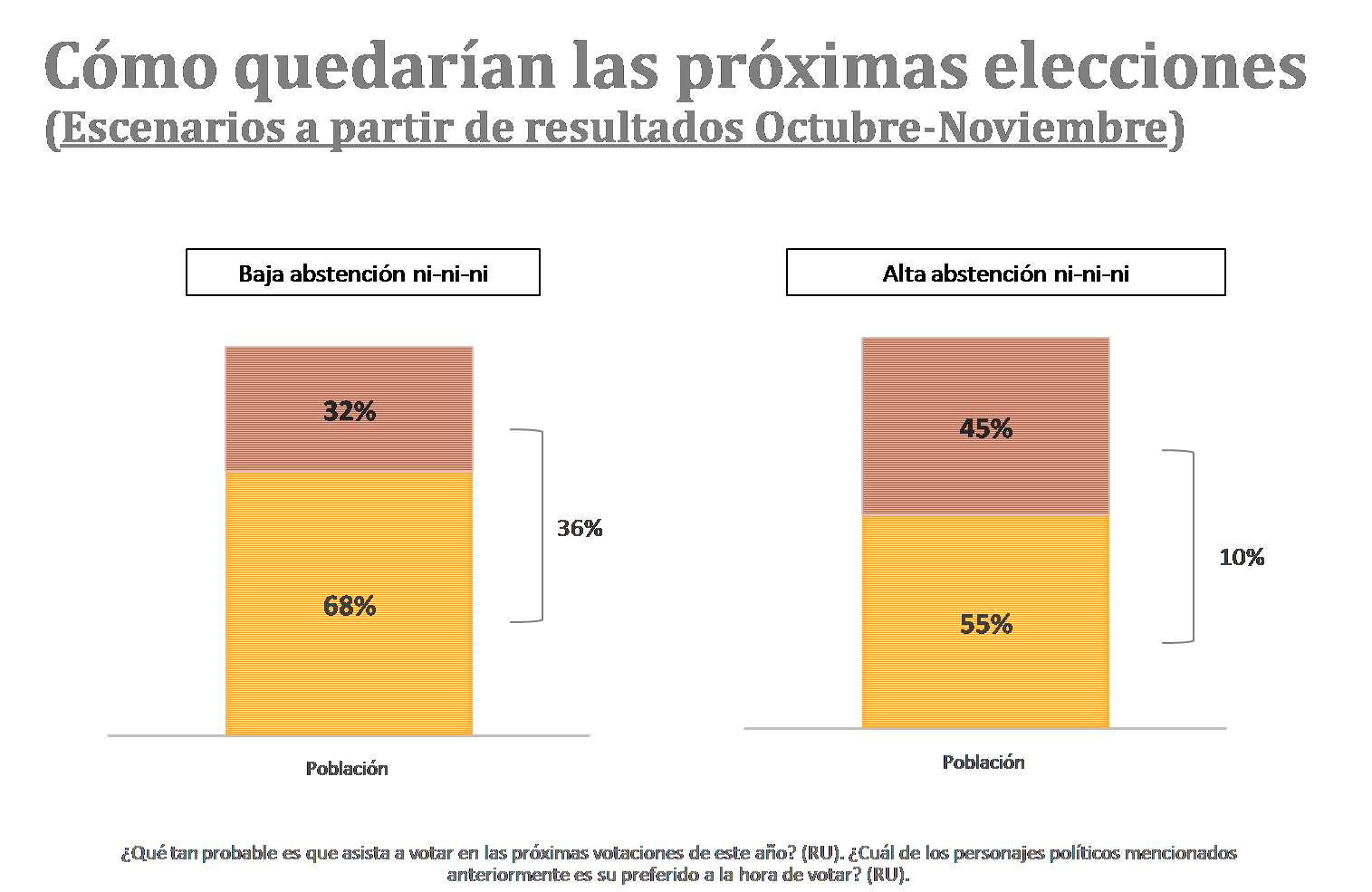

Finally, the result scenarios for 6D: they designed 2 hypothetic possible results, depending on turnout level. In both scenarios opposition will win in national vote: the gap will be more than 30% in case of high turnout, but could diminish to a difference of 10% if ni-ni-ni turnout is low.

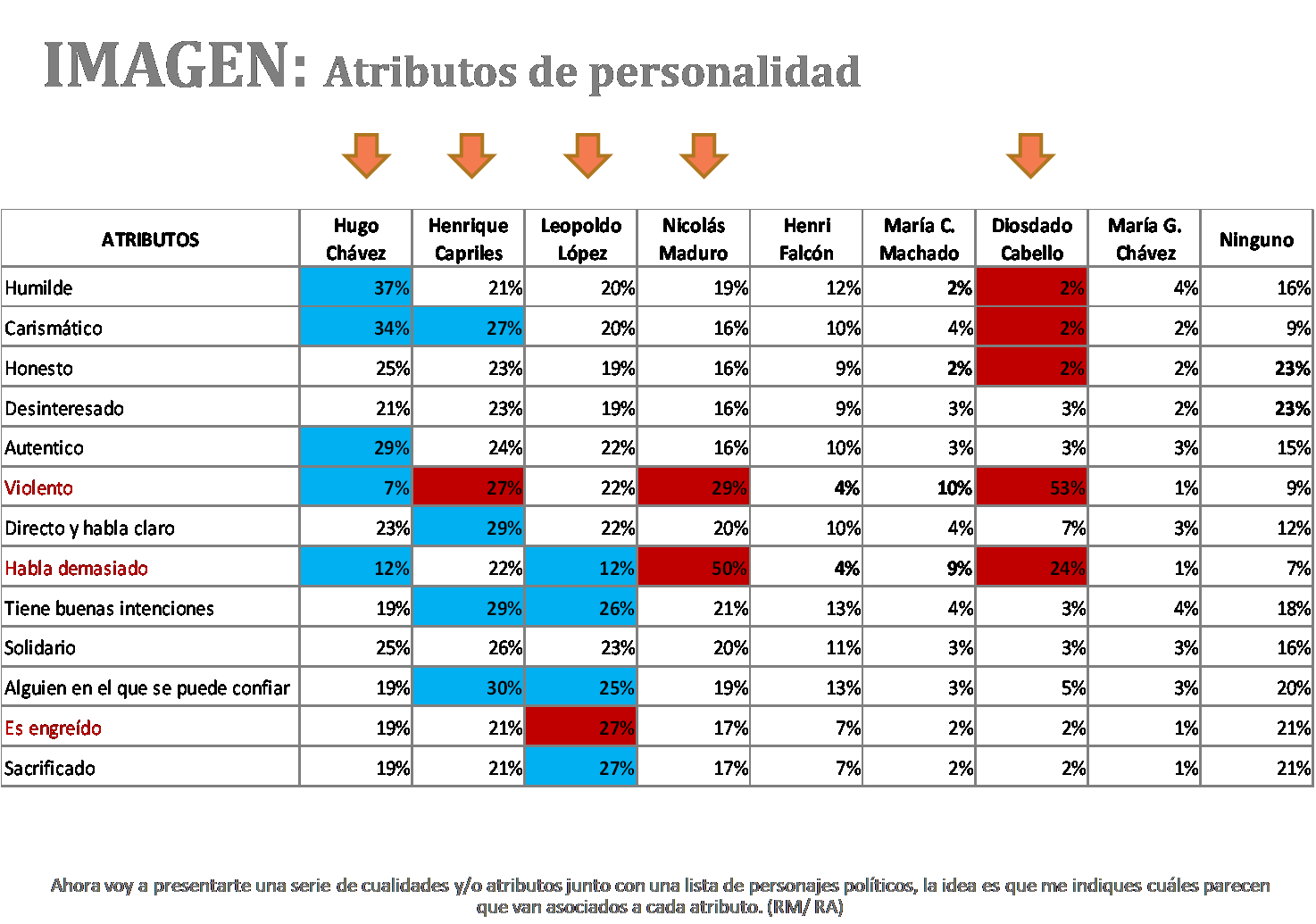

An interesting additional finding was how chavismo and opposition leaders are perceived by Venezuelans, which personal characteristics are attributed to them and what people think is needed to be a good president. Nicolás Maduro and Diosdado Cabello are both very badly evaluated in all measures. Interestingly, people apparently don’t see clear differences between Henrique Capriles and Leopoldo López. We all were amazed watching how people still have such a positive image of Hugo Chavez, so dissonant with what he actually did as a political leader. But understanding people’s views is urgent in order to achieve political changes in Venezuela.

No one left, despite the two hours talk, the multiple questions made by the public, and the not so optimistic results. The talk lasted until Lugar Común closing time and there was a toast for Encuestas Libres launching. Until now, this research has been supported by the team working on it, but now they have started to publish their results (you can read them in their website) and they intend to begin a crowdfunding campaign to make this effort sustainable. Information is power, and I think this open access initiatives are central for democracies in the 21st century. For me this is another evidence of how Venezuelan society is moving, innovating and shaping its future; one more reason to be hopeful.

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 22 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate