El Furrial: The Spectacular Decline of a Giant Oil Field

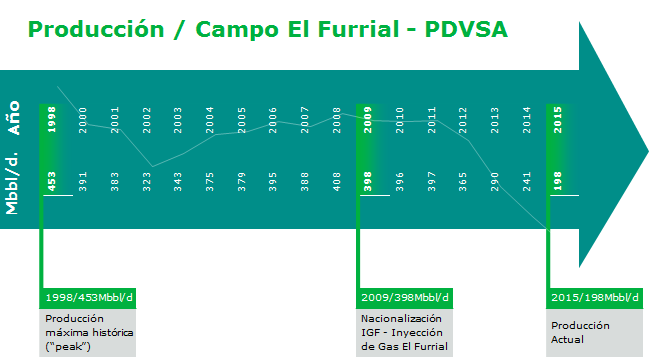

El Furrial, once the jewel in PDVSA’s Crown, has seen production collapse from 408,000 b/d in 2008 to 198,000 in 2015: a catastrophe that is costing the country untold millions of dollars each and every day. What happened?

“I wanted the whole world or nothing.”

Charles Bukowski

Drive half an hour along the flat, sweaty lands west of Maturín and you come to the little town of El Furrial. Known as the birthplace of Diosdado Cabello, El Furrial is more properly famous as the site of one of the richest, but also most challenging oil fields in Venezuela. It’s not the only big field in Monagas, of course —there’s also the rest of the Norte of Monagas’s mighty fields, including Santa Bárbara, Jusepin, Carito, Pedernales and Quiriquire. They’re some of the most valuable and productive oil fields in Venezuela, with the added bonus that they produce light and medium grade crude, not the gunky extra-heavy oil you find further south in the Orinoco belt.

Even in an area of hugely rich oil fields, El Furrial stands out. It’s the newest and largest field around, and it’s the most recent onshore non-Faja giant field to be discovered in Venezuela. At the time of its discovery in 1985-6 its proven reserves were about 4 billion barrels. That’s enormous: at that time, that single field had oil reserves as big as Indonesia —an OPEC member, no less— and almost twice as much as all of Colombia. El Furrial has so much oil that PDVSA has an entire division dedicated to keeping this monster as the top producing field in Venezuela. It reached its peak in 1998 when it produced 453,000 b/d —a little less than Ecuador produces now. You get the picture: El Furrial is a monster.

But it’s not just about the quantity of oil that comes out of El Furrial, it’s about quality, too. The field produces light and medium crude. That’s key. As you know if you’ve read “The Shocking Potential of Natural Gas and Condensate” by a guy who goes by the nom-de-blogue Guevara de la Vega, Venezuela has been increasing its extra-heavy oil production and suffering acute shortages of lighter oil to mix it with.

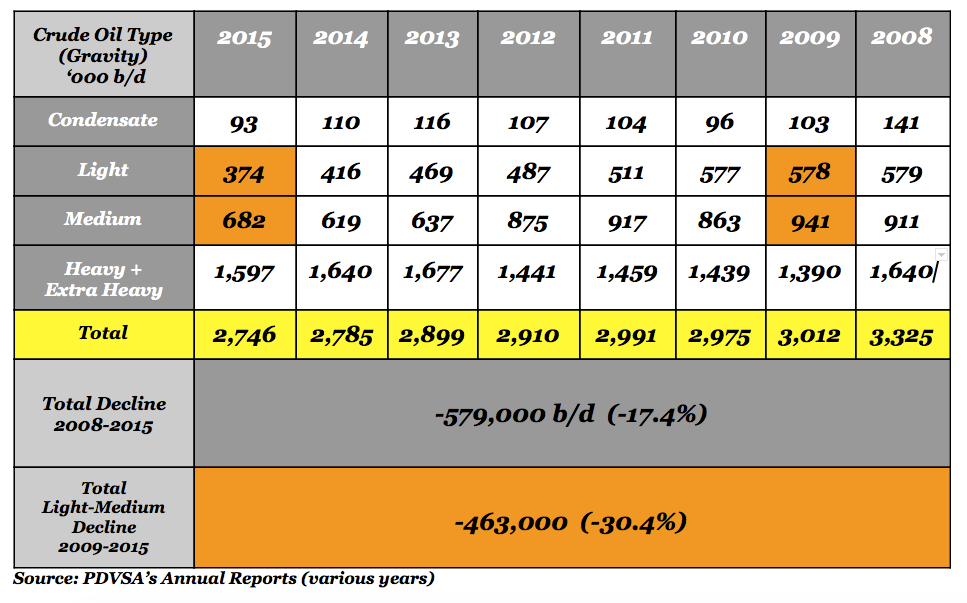

PDVSA Production 2008-2015

In the same period, Iraq, increased its total production in 1,58 million b/d (+54%).

A Challenging Giant

Although prolific and large, El Furrial’s geology is notoriously challenging. It’s very deep and asphaltene is a big problem. Asphaltene is something you don’t want with your oil because it plugs into the wellbore tubing and valves and makes a mess of your operation (a lawyer talking about reservoir engineering and well management, fin de mundo).

The asphaltene problems at El Furrial are notorious. So much so that every reservoir engineer in the world knows about them. El Furrial is in every oil field management textbook, the Society of Petroleum Engineers (SPE) has published a number of papers on it. Go to an oil field management/engineering reservoir conference and chances are you’ll run into someone presenting a paper on this topic.

The details get technical very fast, but the for-dummies version is that to keep oil flowing out of El Furrial, you need some sophisticated techniques collectively known as enhanced oil recovery (EOR) —you gotta keep the pressure up, you have to handle the asphaltenes, the associated water, the sand, a whole mess of details. First a water injection project was introduced in 1992. Later, a gas injection program called Planta de Inyección de Gas a Alta Presión El Furrial (IGF) came online in 1998. That last project was built, owned and operated by Wilpro El Furrial, a consortium of two American companies (Williams and Exterran).

Wilpro El Furrial managed to accommodate the revolution relatively effectively for a decade. Although PDVSA had owed it money (la mala costumbre of not honouring its debts is nothing new) relations were relatively stable until early 2009. That’s when the wheels came off, when the government decided it wanted to nationalise the oil services industry in one go, including of course, the gas injection projects.

The risks were clear. According to two Wikileaks cables from March and April of 2009, the US Embassy, after a meeting with consortium representatives, said that,

PDVSA’s ability to assume operation of the water and gas injection services of the Wood Group and Williams respectively is doubtful. The technology involved in the Wilpro projects, however, is markedly more complex than that used by the Wood Group [a water injection project on the Maracaibo Lake, also nationalized] and that would, we assume, enter into any calculation to nationalize the plants. A take-over of these facilities would undoubtedly affect future oil production [US Embassy in Caracas – Cable 09CARACAS362 – 23 March 2009 – Wikileaks.]

PDVSA did nationalise the project and the predictions in the Embassy’s cables turned out to be accurate. It was a mistake.

By losing Williams’ expertise in operating and maintaining these high technology facilities, PDVSA stands to see a significant hit on production in the short-medium term.” [US Embassy in Caracas – 09CARACAS545_a – 30 April 2009 – Wikileaks]

PDVSA and Williams couldn’t reach an agreement on compensation for the nationalisation-turned-expropriation. The consortium partners filed an ICSID arbitration against Venezuela. Eventually they settled for $420 million. Apparently, though, compensation has not yet been paid in full, because the arbitration appear as “pending” on the ICSID web page. (Or is there another explanation for that?)

From 2009, PDVSA took over the water and the gas injection operations…and production began to fall fast almost immediately.

The High Tech Bit of the Oil Industry

El Furrial’s troubles are the troubles of a whole industry. As Venezuela’s production operations have become more complex, the country’s been forced to rely more and more on high tech oil field service contractors like Halliburton, Schlumberger, Williams and Wood Group.

The problem is that these companies have long been owed huge sums in unpaid invoices, so some have scaled down operations or left the country for good. The companies used to complain to PDVSA discretely, but more recently they’ve learned it pays to go public early. This sets off alarm bells in La Campiña. PDVSA puts on a charm offensive: offering token payments and repeatedly make promises that they will pay up. Recently, the company seems to have settled on a solution: paying off old bills with bonds or promisory notes. Haliburton recently agreed a deal along these lines, others are under discussion. Comida pa’ hoy, hambre pa’ mañana.

Schlumberger plays a special role in all this. The company has been in Venezuela forever: it made the first electrical well log in the Americas in Cabimas in 1929. The company seems to have been brought back in to patch up the mess PDVSA made in El Furrial. It listed a well intervention there as one of the highlights on its 2015 4Q Results.

That PDVSA is still relying on the likes of Schlumberger to keep El Furrial in production is an especially bitter irony. The government has long accused the service companies of a “silent sabotage”. From 2006 on, in order to lessen this dependence and to shield itself from an improbable second paro petrolero, PDVSA started to acquire drilling rigs, well completion equipment, gas and water injection facilities, etc. This was just a piece of the “total sovereignty over oil” puzzle. As then President of PDVSA-cum-Minister, Rafael Ramirez, put it, they wanted to create “Our own Halliburton, the Bolivarian one”.

But plans didn’t go as planned.

A Botched Nationalization

In May 2009, as part of this buying and expropriation spree, the PDVSA roja-rojita made what I personally consider the worst tactical mistake in 17 years full of mistakes: nationalising the oil service sector.

Oddly, I’m not the only one who thinks so. Just yesterday, PDVSA’s President and Minister of Petroleum, Eulogio Del Pino went in front of Venezuela’s Petroleum Chamber, where all oil service providers are reunited, that what PDVSA did in 2009 was a mistake, especially for the Maracaibo Lake oil service providers and operations. Too bad his little flash of insight didn’t extend to El Furrial, though.

Let’s look at the facts. The 2009 nationalizations took aim at three specific activities: gas compression in Oriente (including the PIGAP and El Furrial gas projects), water injection projects (including the Wood Group-lead SIMCO project) and the Maracaibo Lake maritime support companies.

The result? Starting in 2009, production began to decline much faster. The Maracaibo Lake and Norte de Monagas fields were the worst hit. PDVSA’s own data show that.

The Maracaibo-Falcon basin went from producing 1,084 million b/d in 2008, just a year before the nationalisation of the oil service companies, down to 706,000 b/d in 2015 or a whooping 35% less in less than a decade.

As for El Furrial, brace yourselves. Working from PDVSA’s Annual Reports, I charted the historical production and reserves of El Furrial and guess what? The production decline was massive. From 408,000 b/d in 2008, production declined to just 198,000 b/d in 2015. That’s a 51% fall in just seven years. This could only suggest that things haven’t been done properly. It’s normal that the production decline rate of a mature field increases as years pass. But not on this scale.

El Furrial – Production

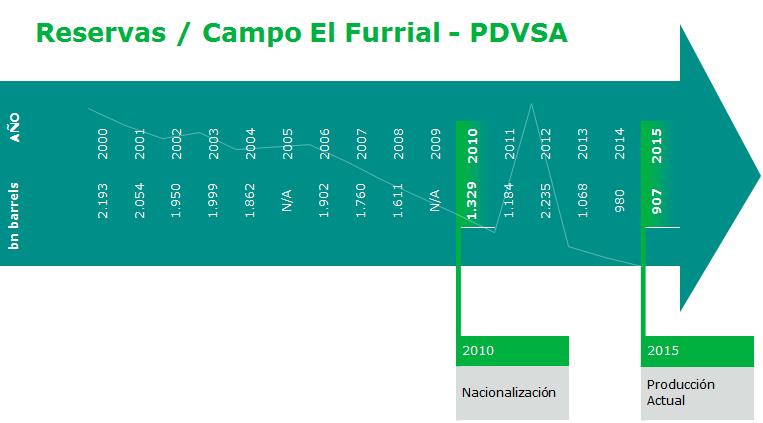

The fall in reserves is even harder to make sense of. El Furrial’s reserves have gone down 58% from 2.19 billion barrels in 2000 to 907 million barrels in 2015. In the seven years after the nationalisation of the gas injection project, reserves fell a shocking 43% from 1.61 billion barrels in 2008 to 907 million barrels in 2015. PDVSA’s data on this are hard to make sense of: in 2012 reserves were put at 2.24 billion barrels, only to then collapse again.

Why? They don’t tell us.

El Furrial – Reserves

You can check PDVSA’s Annual Reports yourself: the trend is repeated everywhere the service companies were nationalized.

The chickens are coming home to roost

PDVSA is paying the price for bad management and disastrous strategy choices at a time when every single barrel counts. The company cannot hope to build its “own Halliburton” if it won’t maintain high standards of professionalism, won’t pay specialised oil field workers properly and won’t get serious about Research and Development (R&D).

Between 2013-2015 PDVSA only invested $388 million in R&D (and a measly $74 million in 2015!). That’s nothing. For reference, Petrobras invested $2.8 billion and Halliburton, the company PDVSA wanted to emulate, $1.67 billion in R&D over the same period.

PDVSA could have gotten serious about crafting an efficient oil service subsidiary —why not? But it didn’t. There’s too much money to be made, virtually no oversight and no shame.

But it’s not the end of the world.

Thank God (literally) Venezuela has plenty of oil and gas, and its industry has everything it takes to remain competitive for quite some time —though not forever.

Sorting this out isn’t rocket science, but it will take time. PDVSA has to get rid of both non-core and complex operations. It has to pay decent wages, invest in its people and invest a lot more on R&D. When it comes to recovering INTEVEP, PDVSA’s R&D arm, pa’yer es tarde. The reform agenda is long. We need a more accountable and transparent industry. This is what I spend my days thinking about, so I’m going to be dealing with it in future posts.

Right now, the A.N. is discussing a bill to “de-nationalize” some of the oil service companies. The bill gives PDVSA more leeway to bring in subcontractors to take on tasks that were nationalized in 2009. I hope PDVSA is on board with this. There is nothing wrong with back-pedaling on a catastrophe.

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 22 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate