Ciudad Bolívar One Month On

As Ciudad Bolívar slowly recovers from the spasm of violence that shook it a month ago in the wake of Billetegeddon, the malandros and the army guys are once more solidly in charge.

I’ve been studying civil engineering in Ciudad Bolívar for the past 6 years, and I finally had my thesis defense there last week. It was one last hurrah for me: I know that after this, I won’t have much of a reason to go back, so I tried to take one good look at it before I left.

I was part of the team covering the Sack of Ciudad Bolívar for Caracas Chronicles, so I was expecting a city in total ruins. Sure enough, just a bus ride into town was enough to see the numerous ripped-up santamarías (metal roll-down gates) throughout the city.

But it was soon clear the city is starting to come back to life. To my surprise, many of the locations I recognized from looting videos are open again. My sense is that the ones that haven’t reopened are largely the Chinese-owned stores in residential areas.

The Cámara de Comercio e Industria de Bolívar (Chamber of Commerce and Industry of Bolívar) says that 75% of the food outlets in town were looted, but signs of looting were obvious in many other stores not linked to food, including tire shops and hardware stores.

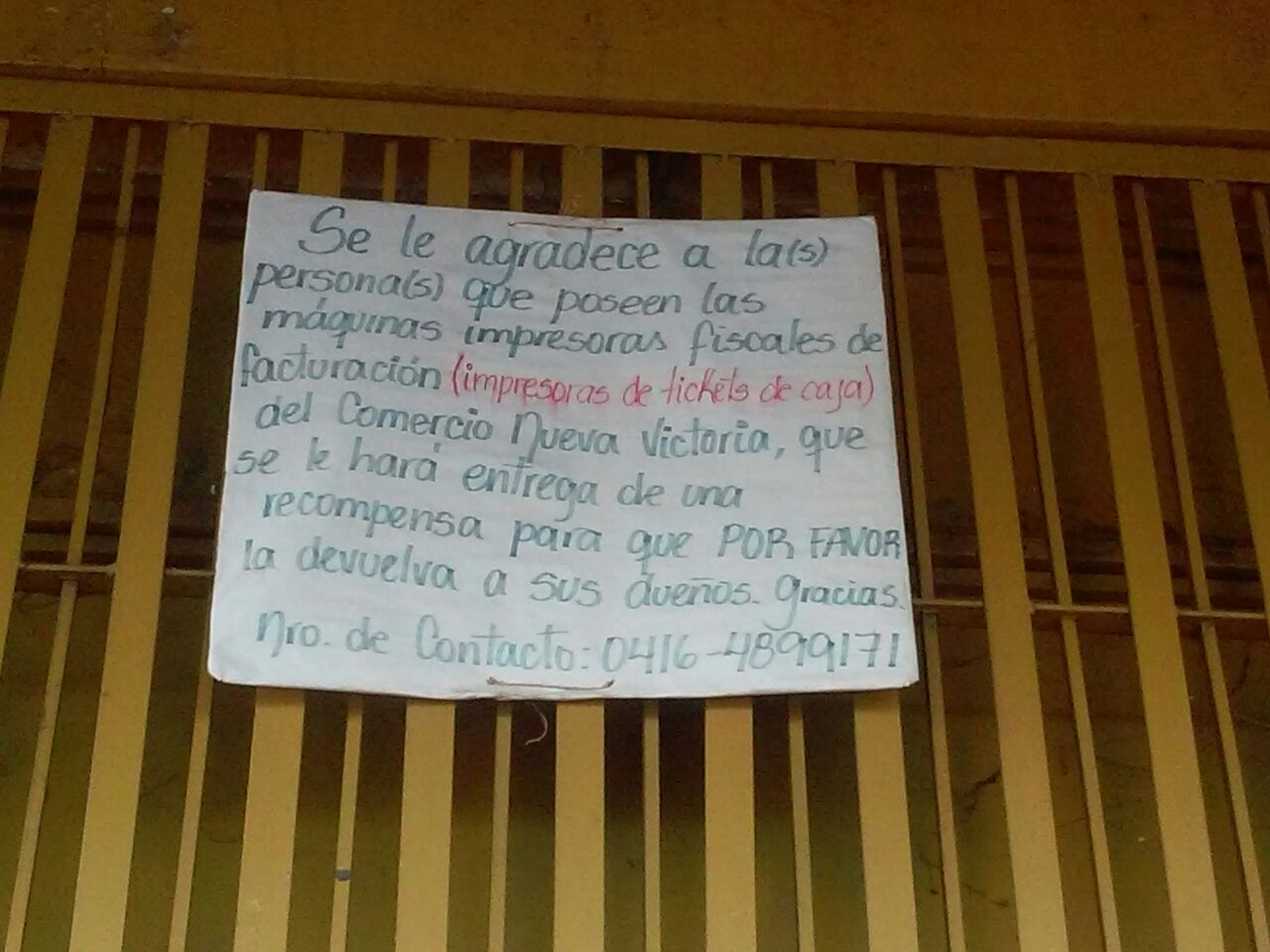

Some shops have signs up offering ‘rewards’ for people who return their looted equipment.

Some places like the Mercado Periférico and Traki enjoyed a permanent military presence throughout the crisis. Those were untouched by the madness.

Some places like the Mercado Periférico and Traki enjoyed a permanent military presence throughout the crisis. Those were untouched by the madness.

The state of the Super Baratón supermarket was the most shocking. As a student, I used to do most of my shopping there. This time I was greeted with reinforced closed gates. It looks like a quarantine zone now.

The new normal

The new normal

But the city is stubborn, and it’s slowly working to recover. The usual vegetable street vendors still set up their tarantines, helping conceal the looted shops. Many business are reopening.

It’s scary how easily Ciudad Bolívar assumed the increasing power of malandros, and the highly visible military presence, as normal.

Conversation is going back to normal too. One girl on the bus talks about some businesses paying Bs.800,000 to the local pran for protection. Rates are going up. Someone else tells me about someone getting help with his damaged car from malandros. Apparently, after helping, the malandros invited the guy to a party and he had to pay them Bs. 50,000 to pass on the invitation.

The looting is just a layer of the many problems the bolivarenses are facing. In one weekend alone I heard about a man whothat got shot for resisting a robbery — the wound didn’t seem that dangerous, but he still died later in hospital for lack of antibiotics. Another friend told me how the car she was in got shot at by thugs, wounding 3 out of the 5 people inside.

Those are the usual stories. “Normal.” It’s scary how easily Ciudad Bolívar assumed the increasing power of malandros, and the highly visible military presence, as normal. It’s just the way things are now.

Scapegoats

On January 12th, the government rounded up its scapegoats for the riots. Roniel Farías, a municipal councilman, and Irwing Roca, a local activist — both from Voluntad Popular — were detained by SEBIN, the secret police. Two weeks later, Roniel Farías is being sent to El Dorado jail, charged with looting, devastation, instigation and aggravation. The only evidence against him was a notebook with handwritten notes that are plainly forged.

In the meantime, the malandros keep increasing their power, just like the government.

If you ask me, the Sack of Ciudad Bolívar went down perfectly for the government. This could’ve potentially turned into a government-toppling crisis on the scale of El Caracazo. Instead, it became just another excuse to hand more power to the military (now in control of local businesses), and the Nth pretext to keep persecuting Voluntad Popular. They even got the owners of the destroyed Super Baratón to thank Maduro for his help.

In the meantime, the malandros keep increasing their power, just like the government. No wonder they are always partying. In Vista Hermosa, where I was staying, you can hear the loud music coming from the jail every night.

Normal.

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 21 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate