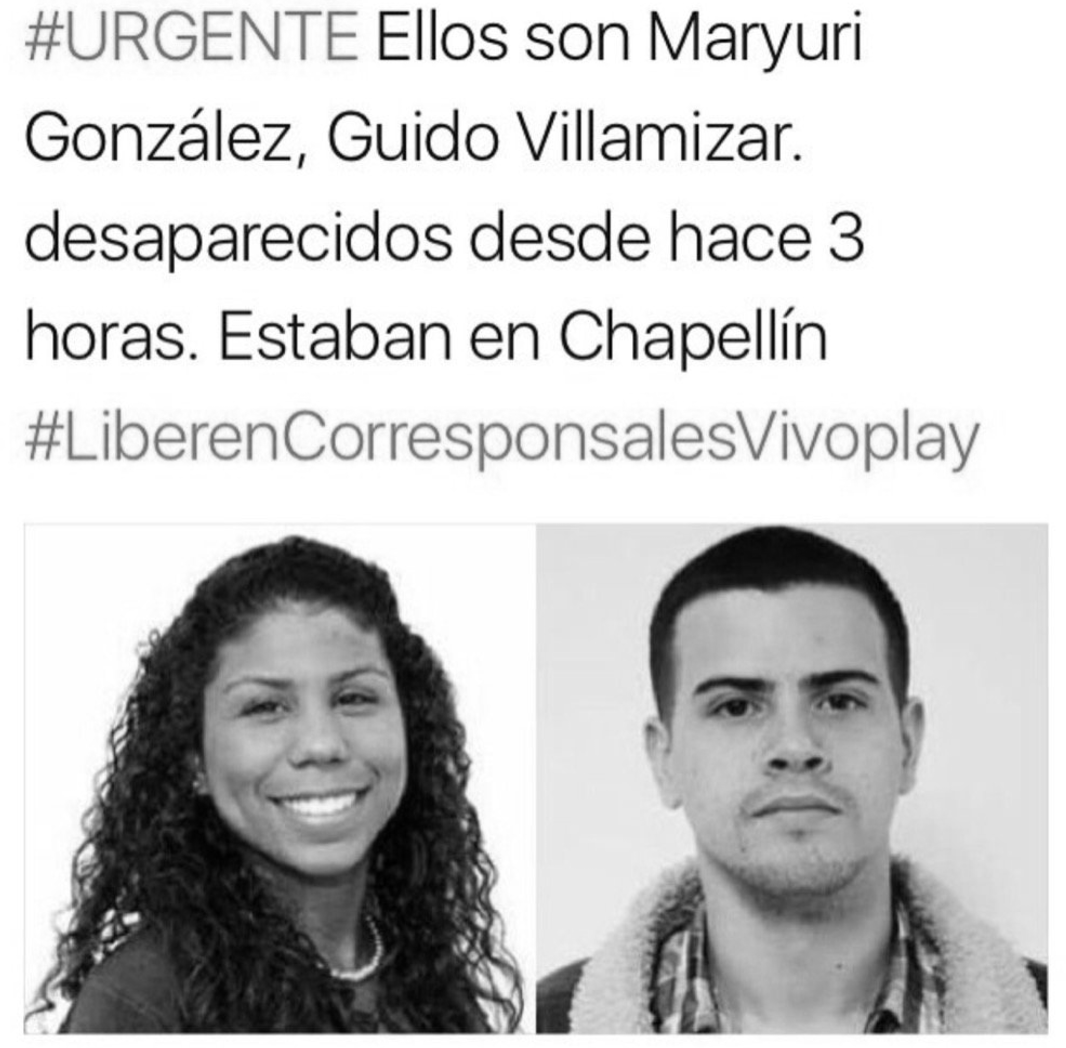

Maryuri’s Story: Arrested for Committing an Act of Journalism

When her online news channel sent Maryuri to cover a cacerolazo, she never dreamed her day would end with colectivos, the National Guard and Military Counterintelligence arguing over who would get to keep her and her team.

Maryuri Andreína González became a war correspondent this year. Not that that was her plan. Reality caught up with her, though. Camera in tow, she’s been learning to negotiate tear gas canisters, Molotov cocktails, National Guardsmen and “colectivos”, but one of the worst moments of her life came on May 1st, after she and her team went to Chapellín, a barrio just off La Florida in eastern Caracas, to report a “cacerolazo” after a day of protests in the area.

Maryuri, along with a producer and two motorizados, were kidnapped by civilians and then detained by officials of the National Guard.

“At first I was scared because I thought it was SEBIN” —she means the secret police— “but later I realized that they were ‘paramilitares’ —just civilians with guns and covered faces. At that point my fear grew. I didn’t know what they wanted,” she explains.

“At first I was scared because I thought it was SEBIN” —she means the secret police— “but later I realized that they were ‘paramilitares’ —just civilians with guns and covered faces. At that point my fear grew. I didn’t know what they wanted,” she explains.

They were screaming at us, telling us that we were ‘terrorists’ as they explained that this was a redada popular —a ‘people’s raid’— inside the barrio.

She was the only woman in the VIVOPlay reporters’ team. As it turns out, one of the colectivo members was also a woman. She’s the one who threatened her, but she says once they realized that “I was the person calling the shots, she became calmer.”

The colectivos who snatched her team were made up of chavistas angry about the protest early that day and the repression that took place hours before. The colectivos saw Chapellín as their territory —“su barrio”— and with the tear gas, they had not been able to get in for a few hours. Now, they were determined to “defend” their turf.

“When we were against the wall, a group of neighbors surrounded us. They were screaming at us, telling us that we were ‘terrorists’ and explaining to us that this was a redada popular —a ‘people’s raid’— inside the barrio,” González says.

They were interrogated, aggressively, out in a barrio alley off the main gas station. A half hour later, another man came asking the same questions all over again. Maryuri asked what authority he had to hold her captive — that’s when the man identified himself as Military Counterintelligence, and stripped them of all their equipment.

He told them what they were doing was a crime because it amounted to “war journalism,” and they were not accredited to do war journalism. It was an absurd charge, and one that only underlined the tight coollusion between the civilian colectivos and the military.

“After that, I felt indignant, later completely helpless. They took my camera and my phone, my ‘weapons’,” she remembered. She felt powerless — but she knew VivoPlay would be doing what they could to free them.

Maryuri takes all kinds of precautions in an attempt to go unnoticed. She knows that the colectivos remember her face.

The wait was long and tense. Chavista neighbors were shouting insults at them from nearby windows, their equipment was laid out on the ground — trophies confiscated after a drug-raid— as they tried to explain they hadn’t been doing anything illegal. At one point, an argument broke out between the colectivos, the National Guard officers and the self-described Military Intelligence guy about what to do with them.

An hour later, it was finally decided the National Guardsmen would take them them to Fuerte Tiuna military base. Weirdly, this was a relief: finally, they were out of the barrio and beyond the colectivos’ hostile grip. They were put on a truck with two other guys, probably also detained that evening. After they arrived to Fuerte Tiuna, they were handcuffed and a soldier explained to them that they were under arrest.

Eventually, the journalists were called to another room and set free. Nobody ever really explained why.

But for Maryuri, reporting work on the protests hasn’t stopped. She took a single day off after her detention and she was right back at it. A few days later she was trekking out to Ramo Verde military prison at night to broadcast Lilian Tintori as she demanded to know what had happened to her husband, Leopoldo López.

They took my camera and my phone — my ‘weapons,’ she remembered.

“The first time I put the equipment on again, the vest, the helmet, I had a panic attack. But I didn’t say anything. But when I hit the street again, the fear was over. I didn’t allow what happened to affect my job. Of course, I’m scared and my family said that it doesn’t make sense for me to risk my life for the money I earn, but this is my way to help bring about the change that I want in my country,” she recalls.

Now Maryuri tries to not use “flashy” clothes and she wears her hair in a braid. She takes a different route to the office each day. All kinds of precautions in an attempt to go unnoticed. She knows that the colectivos remember her face.

For her, fear is part of her job, not only the fear people feel on the streets when she approaches them with her camera, but the chills that she feels thinking through SEBIN arrest scenarios.

“For the police or the National Guard, when you go out on the street with your camera you become a threat to them, but we’re not the enemy, we are just trying to show what’s happening. Just a few hours ago, a National Guardsman pointed his gun at me and I put my hands in the air and said ‘I’m a journalist,” Maryuri says.

The first time I put the equipment on again, the vest, the helmet, I had a panic attack.

At just 27, she sounds confident and as faithful a defender of good journalism as you’re likely to find. But she doesn’t criticize journalists working for government media.

“The government is trying to stay in power by leveraging the absence of information, but in the end, we’re all trying to do our job,” she says.

Her hope for the Día del Periodista is that all media workers band together.

I’m scared and my family said that it doesn’t make sense for me to risk my life for the money I earn, but this is my way to help bring about the change that I want in my country.

“The other day I saw two journalists fighting on the street,” Maryuri tells me. “We all want the to grab a scoop or bring our editor the best photo, but we have to respect one another.”

She calls on all journalists in Venezuela to stay alert, to protect themselves, and to support and defend each other. Meanwhile, as she gets ready to mark the day, she knows she’ll probably spend it covering the protests, running, as usual, between Molotovs and tear gas cannisters.

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 22 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate