No Justice for Bert

Extrajudicial killings happen so often in Venezuela that nobody bats an eye at the figures, and all you need to be part of the statistic is one dose of bad luck.

Original art by Mario Dávila

I became friends with Bert (not his real name) back in elementary school. We grew up together until his parents took him out of our school at the end of the eighth grade; he had failed six courses and had to make up for them in the summer – the dreaded reparación.

Maybe you’re thinking “this dude must be dumb,” but Bert taught himself two languages, and how to play the guitar. He was an avid reader, a poet and a music connoisseur.

A few weeks ago I received a message on Facebook asking me if I knew him. It was written by his girlfriend several days before, but when I answered, she immediately wrote back. And she had very bad news.

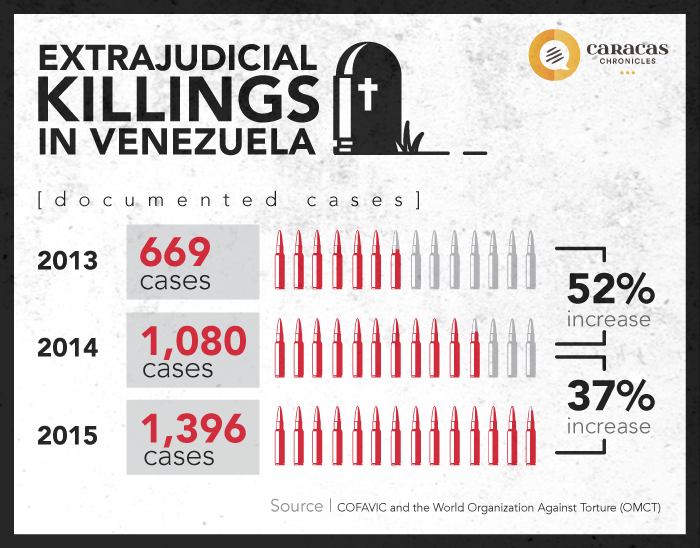

According to the 2016 Report for the Universal and Periodic Exam of Venezuela, by COFAVIC and the World Organization Against Torture (OMCT), a total of 669 cases of extrajudicial killings were documented in 2013; there were 1,018 cases during 2014 (a 52% increase compared to the previous year) and 1,396 cases for 2015 (a further 37% increase).

30% of all these cases were attributed to the Criminal Investigations Police, known as CICPC.

Bert, a proud guy who hated pity and condescension, was a foreigner to that statistic until he inexplicably wasn’t. A warrior from the start, he had to care for one or both of his parents far too early in life (one struggled with substance abuse, the other with mental illness), yet no matter how dark it got, we would always find strength in each other. We were a team and our friendship made me feel young, carefree, even reckless. He was like you and me, and we were alive.

The last time we spoke was about a month and a half before that horrid Facebook message. We chatted about life, about music and about how tough it was getting for him and his mother. She was sick, she had cancer. His dad had died five years earlier, also of cancer, and now Bert was in charge of the bills, barely making it to the end of each month.

Desperate, he became a gold miner, hoping to get dollars for the chemo his mom needed. He never thought he’d find himself in such a situation because, even without a college degree, he’d had all kinds of jobs. But by 2017, having a regular job wasn’t enough for food, let alone medicines at black market prices.

Barely twelve hours passed after his detention when he was murdered under police supervision.

Now he’s dead. That’s what his girlfriend told me, and it still echoes in my heart.

On September 11, 2017, El Nacional reported on two extrajudicial killings. Committed by CICPC officers, they happened in plain sight of bystanders, including the victim’s families, who remarked that nothing was done that could conceivably justify the bloodshed.

The COFAVIC/OMCT Report says most of the victims were less than 25 years old (81%), and 99% were male, most of them from slums. Other Human Rights violations reported include torture, rape, arbitrary detentions, violence against women and forced disappearances.

Truth is, nobody actually knows how my friend died – and what his girlfriend knew, she knew from rumors. There was never an official report and authorities are indifferent to questioning. This is all we know:

Bert went to the hospital to see his mom. She wasn’t doing well, and they ran out of money for the hospital bill. He called his friend Edmund, because he needed cash for a cab, but nothing was arranged. Somehow, Bert got home with his mom; witnesses say she was in very bad shape and versions differ: some say neighbors called the CICPC because of the ruckus, others say it was Bert who called, after his mother died.

The CICPC arrived around midnight, and Bert was accused of manslaughter (allegedly, his negligence caused her death). When Bert’s family showed up the next morning at the CICPC jail, they were informed that he was dead. Just like that.

Bert and his mom were victims of what life in Venezuela has become.

Bert and his mom were victims of what life in Venezuela has become.

If the past foretells the future, there will be no justice for him. He didn’t get a trial or an investigation before he became an inmate, and barely twelve hours passed after his detention when he was murdered under police supervision.

It’s not only that the system isn’t built for these cases, it’s plain hostile to them. Standard operating procedure is to ignore these kinds of deaths, or rewrite them so they don’t look like the Human Rights violations they are. The sickest part? This is just one case in a country where murders in jails happen so often that they’re expected.

But victims are not just a number on a report. Just look at Bert; step on the wrong toes, and you might be next.

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 22 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate