Three Diseases, One Truth

The International Council of AIDS Service Organizations and Acción Ciudadana Contra el Sida just released their report on three Venezuelan epidemics. The scenario is horrifying.

We’ve been talking for some time about how serious the Venezuelan health crisis is, but accurate data is hard to find. That’s why every report offering quantification on how bad things are deserves a full read.

Case in point: Here’s a joint investigation by the Canadian-based International Council of AIDS Service Organizations (ICASO) and Venezuelan NGO Acción Ciudadana Contra el SIDA (ACCSI). After interviewing over thirty people, including patients, doctors, activists and UN personnel, the project concluded three diseases (Malaria, Tuberculosis and HIV) are becoming critical threats to national and regional public health.

Malaria is growing at a rate never seen before, tuberculosis has found new breeding ground in overcrowded prisons and neglected indigenous populations, and HIV patients are dying 75% more than in 2011, as drugs meant to stop the virus have arrived irregularly for several years.

Three diseases (Malaria, Tuberculosis and HIV) are becoming critical threats to national and regional public health.

The report also points out how unprepared the world is for a humanitarian crisis regardless of the country where they happen, and the Venezuelan government’s negative to acknowledge the situation – with a shot taken at the Global Fund to Fight Malaria, AIDS and Tuberculosis, for denying humanitarian aid to HIV+ patients.

A broken country

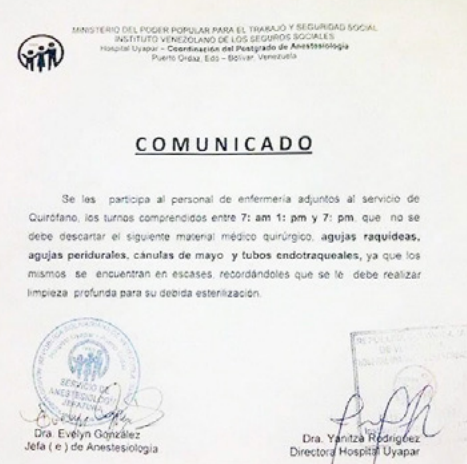

As imports decrease and inflation erodes Venezuelans, access to food has gotten difficult: a single 30 eggs package can take away up to 80% of a family’s monthly income. Malnutrition came back in early 2017, reaching 15,8% of kids under five by July. The already damaged hospital network is also affected, with 76% of surveyed hospitals facing extreme shortages and lack of medicine affecting almost 70% of the World Health Organization’s (WHO) list of essential medicines. The situation is so bad that in some institutions, like Uyapar Hospital in Puerto Ordaz, personnel is being instructed to reuse disposable syringes and endotracheal tubes. There’s a picture of the memo in the report.

Malaria

We’ve reported on malaria several times, but now it’s revealed that cases in 2016 increased 76% compared to 2015 (240,613 cases nation-wide).

The boost is so dire that it jeopardizes countries like Brazil or Colombia. 78% of cases in Brazil and over 80% of those in Colombia and Guyana came from Venezuela.

The report suggests that the lack of antimalarial drugs is forcing patients to get sub-therapeutic doses of those meds, increasing resistance against them. The situation might be harder for isolated indigenous villages: in May 2017, 25 Joti communities (an indigenous group from the selvatic Bolívar and Amazonas states) released a statement urging the Health Ministry for help, denouncing over 3,700 cases of malaria in a 900 people town (meaning, the same person gets infected multiple times through the year). Patients had been forced to split their limited drug supply to distribute it among all affected.

“In the second quarter of 2017, four indigenous Joti walked out (of their community in Caño Iguana) with a malarial child to seek help. After a 12-day march, they arrived in Puerto Ayacucho. The child died before receiving any medicine,” an anonymous Venezuelan doctor says in the report.

HIV/AIDS

The real number of HIV patients currently living in Venezuela is hard to tell. Official estimates indicate around 100,000 patients, but unofficial data varies from 200,000 to 1,200,000. In 2011 approximately 1,900 people died of AIDS-related infection and 3,300 did in 2015 (a 75% increase in 4 years). The report notes that data on HIV-testing or use of condoms is not available, making real numbers impossible to determine.

Almost 10% of the 25,000 Warao might be infected, and most of those infections could have occurred in less than a year.

An inefficient access to antiretrovirals (ARVs) is to blame for those deaths. Until a few years ago, the National Venezuelan HIV program guaranteed up to 12 different free ARV combinations to about 75,000 enrolled patients across the country. Since January 2016, recurrent scarcity of these drugs has been reported and, by September 8th, at least 11 drugs were reportedly stocked out nation-wide, leaving thousands of patients with different treatments than the ones they used to receive or without any at all.

Due to the pervasive scarcity of baby formula, infected mothers have no choice but to breastfeed their kids, risking transmission of the virus. This is a problem we’ve addressed before, and that threatens to increase the already alarming, and probably underestimated, number of over 1,200 children currently living with the disease.

Indigenous communities are hit particularly hard. A 2013 study suggests that almost 10% of the 25,000 Warao (an indigenous people living mostly in Delta Amacuro state) might be infected, and most of those infections could have occurred in less than a year. The number of Waraos infected is doubling every nine months, said Flor Pujol, from the Venezuelan Institute of Scientific Investigations (IVIC).

“I fear that if all of us, but in particular the Government, don’t do something urgently – and sustainable – the Warao ethnic group will disappear,” said Dr. Martín Carballo, an infectologist following this case closely.

We are talking about the second biggest indigenous group in Venezuela, facing extinction due to HIV.

Tuberculosis

Data about tuberculosis is controlled directly by the military, whose unwillingness to publish it made it hard for the authors of this report to reach accuracy. However, during a meeting with WHO officials, Venezuelan authorities confirmed that tuberculosis cases have multiplied. Five states (Distrito Capital, Delta Amacuro, Portuguesa, Amazonas and Cojedes) account for 52,% of all cases. Indigenous groups are, again, the most affected by the disease, followed by diabetics and prisoners. The situation in prisons is particularly dire. Just in the Preemptive Arrest Center of Lake Maracaibo’s East Shore, in Cabimas, Zulia, eleven inmates have died of tuberculosis this year. According to the report, failures in diagnosis and overseeing of patients are pervasive, with most required tests completely unavailable outside Caracas.

The international role

The Global Fund is sort of an international war chest to fight Malaria, Tuberculosis and HIV. To get financing, countries must meet eligibility criteria one, which is the income classification (the other is disease burden). In 2016 and 2017, Venezuela’s income met eligibility criteria but it’s disease burden didn’t.

Ever since 2016, Venezuelan AIDS activists have been consistently asking for international help. They wrote a letter to the Global Fund, asking that exceptions be made; after 7 months, the answer was negative.

“We need to denounce the [Venezuelan] government for their inaction, and many of the international community for their hypocrisy. Governments that had and have the possibility to help because they have the resources (or the influence) haven’t done it” said an activist who wished to remain anonymous.

Venezuela could be eligible if it meets the burden disease criteria, yet lack of epidemiological data makes this hard. The Fund doesn’t consider indigenous people to be a key population, so the horrid numbers among the Warao we discussed don’t meet the criteria.

The World Bank offered help, and PAHO and UNICEF have provided some help from their own funds, but larger actions are needed immediately. The Global Fund should simplify eligibility criteria, since the Venezuelan state won’t guarantee the right to health.

The report calls Venezuela “a case study” with the crisis being “the result of long process of political unrest and bad economic decisions.”

And this is without including diphtheria and measles, two growing headaches that could turn our triple threat into a quintuple.

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 21 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate