That Bitter Scribble

Like a mocking gift from the past, I just found an old medical book with El Comandante’s signature in it, a bitter reminder of how things were when he signed it, and how hopeless the scene is now.

The Maternity Hospital where I was doing part of my Obstetrics internship last week is located in Ejido, a small bedroom city 9 km west of Mérida. It’s a small place, with capacity for eight patients only, a tiny Delivery Room, and an even smaller Operation Room where only carefully planned c-sections are performed. It’s not designed to deal with emergencies, so you usually have time to spare during the night. During one of those calmed shifts, I found something I wasn’t expecting at all: a souvenir from El Difunto himself.

Standing on the Evaluation Room desk there was a big, old book. The thin layer of protective plastic wrapping it was falling apart and what had once been a blue cover had lost much of its flair. Still, the title was clearly visible: Guía Spilva de las especialidades farmacéuticas, 1999. The Guía Spilva is a classic in any Venezuelan doctor’s bookshelf. First printed in 1954, this book has a list of all drugs commercialized in Venezuela, along with its presentations, doses, commercial names and a list of pharmaceutical companies producing them. It’s published every two years, to keep it updated with changes in a once dynamic market.

Hugo Chávez, the man responsible of the worst economic crisis this country has ever witnessed, had signed a book listing all the medicines available in 1999’s Venezuela.

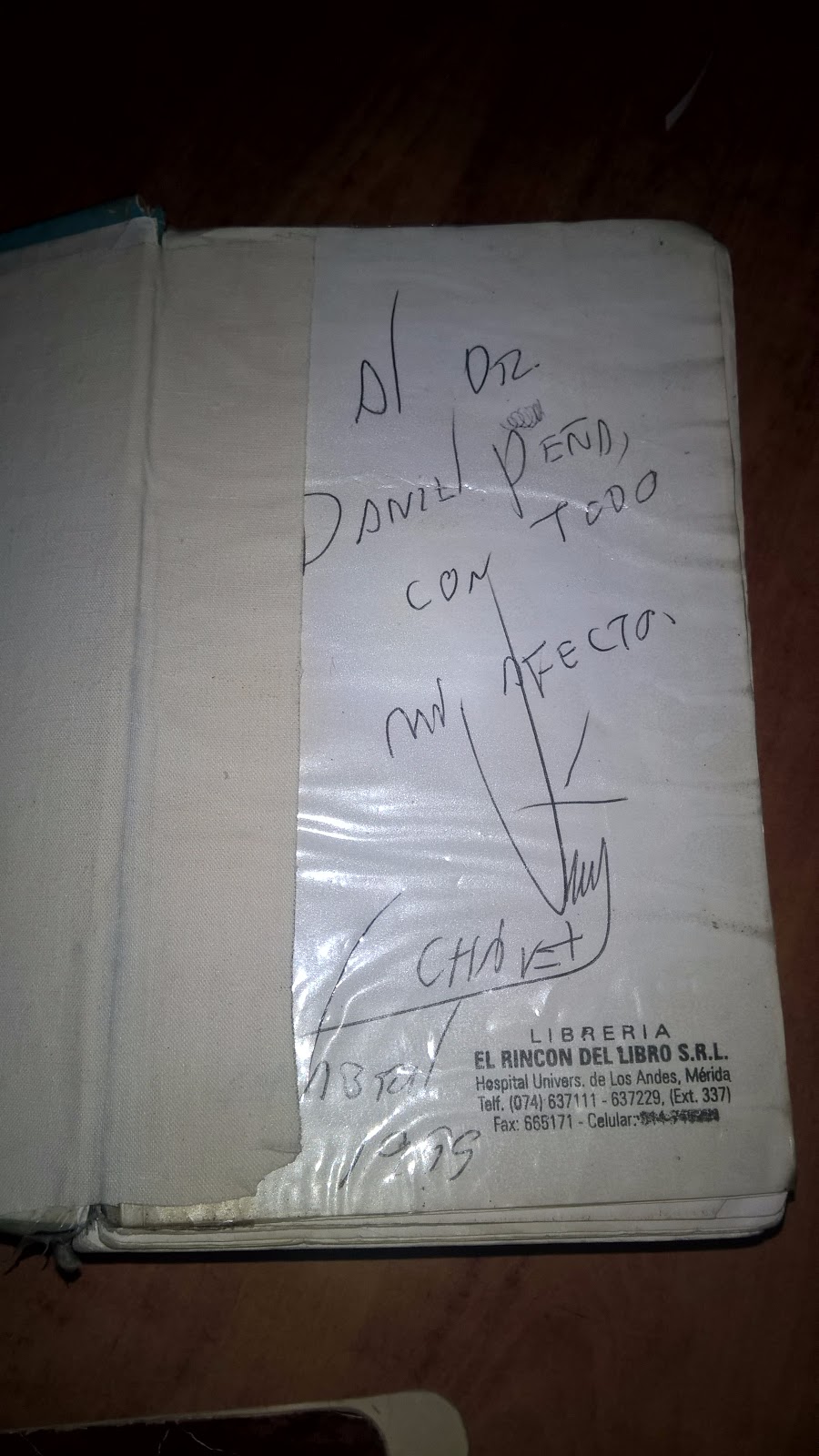

I didn’t get why someone would keep an old, outdated pharmacological guide out of the trash, until I saw the first page. Covered with a foil of the same transparent plastic protecting the cover, there was a big scribble in black ink. Hugo Chávez’ unmistakable signature was written in the middle of the page, dedicating the book to its former owner, some random doctor who I guess worked here once.

It was weird to touch something the man responsible of my many years of piled up anger held in his own hands two decades ago. I was Harry Potter facing Tom Riddle’s diary, it felt almost like touching a book that could spark some dark magic that’d bring El Comandante back. I then realised how appropriate the scene was: Hugo Chávez, the man responsible of the worst economic crisis this country has ever witnessed, had signed a book listing all the medicines available in 1999’s Venezuela, medicines impossible to find 18 years later due to the corrupt, nonsensical model he unleashed upon us.

Irony is a magnificently sad thing.

Take, for example, Buscapina, page 431: an antispasmodic commonly used for stomachache and as part of the protocol to prevent preterm labor, a condition where babies are born too early. You’d expect this drug to be easily available in a hospital that only treats pregnant women, right? Well, it’s nowhere to be seen. Buscapina simply disappeared from the country after Boehringer-Ingelheim, the company producing it, ceased its activities in Venezuela, two years ago.

You won’t find antibiotics like Cefazolin, Cefalotin or Cefadroxil anywhere at Ejido’s Hospital but in pages 15, 20 and 17 of that old Guía Spilva, even though every single woman giving birth at the place should receive them to prevent postpartum infections.

Other drugs didn’t appear in the guide, since the Health Ministry never considered them necessary enough to be imported. That’s the case with Atosiban or Hydralazine, first choices to treat preterm labor and gestational hypertension, respectively. We were taught in med school that in case you can’t stop preterm labor, at least you should be able to speed up the maturation of the fetus’ lungs by using steroids. Betametasone, the intramuscular steroid used in these cases is listed three hundred and nineteen pages after Chávez’ rabo e’ cochino, yet the Maternity Hospital stock ran out of it last weekend.

Chávez’ signature isn’t only present in that eighteen year-old book. I can see it printed in the brand-new Chinese ambulance parked in front of the building, whose brakes broke a couple weeks ago, or in the face of that skinny 17 year-old girl who came in a few days ago, whose father was killed before she met him, currently pregnant with her second son; it’s indelibly written in the tearful eyes of the old nurse whose salary can’t buy her enough food for three daily meals and in the young, recently graduated doctor supervising us, who plans to leave the country as soon as possible… Chávez’ signature is present all over the place, all over the country and all over our lives.

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 22 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate