Buried by Hyperinflation, Metro de Caracas Employees Can’t Afford to Work

A Metro employee was fired because he complained on social media his salary wasn’t enough to buy detergent so he could wash his uniform. Others don’t show up for work, others quit to hawk coffee out of a thermos. Are we nearing the end of the Metro?

Over 40% of subway employees aren’t showing up for work due to low wages and the Metro’s dwindling service conditions.

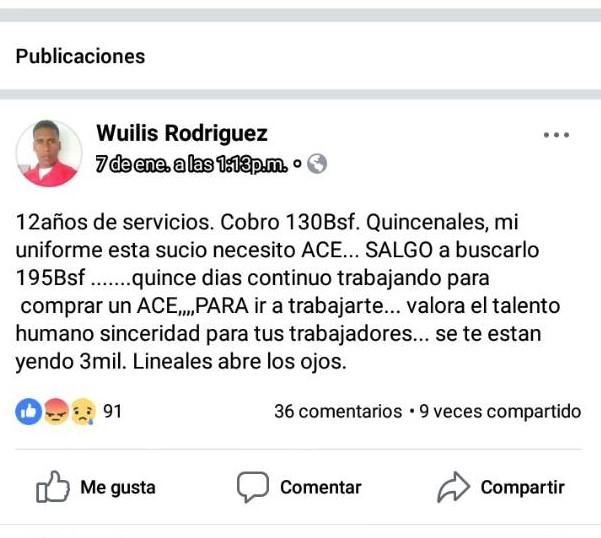

“12 years of service. I earn Bs. 130,000 each quincena ($0.72), my uniform is dirty, I need soap. I go out looking for it and find it at Bs. 195,000, fifteen continuous days of work to buy ACE, to go work for you. Learn to appreciate human talent, sincerity towards your employees, 3,000 of them are leaving. Open your eyes.”

That’s what Wuilis Rodríguez wrote on January 7 at 1:13 pm, both on his Facebook wall and on his Twitter account.

He needed to buy soap to wash his uniform. On the way, his daughter asked him for candy and he wanted to buy some for her. “I though the soap would cost Bs. 70,000 and the remainder of the quincena would be to please my daughter. It was Bs. 195,000 per kilo ($1.09, more than he earns) and I couldn’t buy her anything. I was so depressed by that, and that’s why I wrote on my social media.”

It was the first time Rodríguez used social media to protest. 15 days of work vanished on soap.

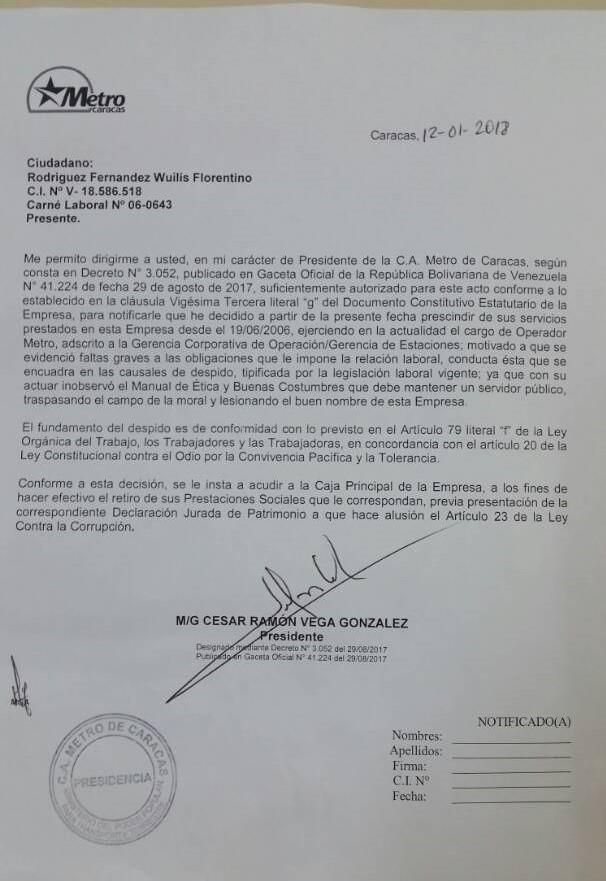

“I didn’t even mention the company in my tweet. But that was enough for them to fire me.”

Since the day he posted, the coworkers he met at Teatros station asked him whether he’d gotten the termination notice. Everyone in the Metro de Caracas is careful not to criticize the company (especially in public) for fear of reprisal. On Friday 12, a company lawyer visited him, putting and end to his days as Security Operator.

Rodríguez’ post resonated with the voice of many others who are still employed but are not protesting with their absence. Over 40% of employees aren’t checking in, discouraged by low wages, poor management and lack of investment in the system. The figure comes from the estimates of the company’s recently created Front of Employees, Retirees and Pensioners, an office that monitors daily job attendance in subway stations and compares it with the company’s internal records without anyone knowing, since those responsible for feeding the office its confidential data are full-time employees who could find themselves in Rodríguez’ situation any day.

A general collapse

The collapse is most evident in Line 1, which connects the city from west to east through 22 stations. 42 trains should do the route during rush hours, but they’ve only been able to use 18 for the past three months, due to staffing and technical issues.

“The trains are driven by my milicianos and operators who have been doing administrative work for years,” says Luis Bravo, who’s been working in the subway for fifteen years. “That’s why the problem is still not that obvious. We’re so discouraged, precisely because many of our coworkers aren’t reporting for work.”

Bravo (not his real name) is on an inter-daily watch. In order to arrive to his station, he pays a bus fair that’s almost 30% off his monthly salary.

42 trains should do the route during rush hours, but they’ve only been able to use 18 for the past three months.

“It’s barely enough. I don’t have money to go to the station sometimes.”

Others, Bravo said, are filing for medical leave or saying that they have academic engagements, or that they couldn’t make it work because they were queuing to buy food.

“They’re taking their leaves in compliance with the collective bargaining agreement and that’s why you see the empty booths,” he said.

On average, there should be between six and eight operators in a booth, two of them working on security like Rodríguez. If you see a sign on the booth’s window saying that there are no tickets available, that’s because there are no operators. The government owes them their wage hikes along with night-time and holiday bonuses.

No longer the great solution

The Metro was inaugurated 35 years ago with the firm goal of being “the great solution for Caracas” and it was, for decades. The debacle started in Chávez’ time, when qualified career employees were laid off in the aftermath of the oil strike. The payroll was filled with co-op companies and soon several pro-government operators filled the vacant posts.

300 operators have resigned in the last three months. 17 more did it last week, while many others haven’t returned to work from December holidays. On January 8, a system strike was announced and later denied by the company’s board.

The employees say that there’s no need to call for a strike because there’s been a technical strike for the past four or five months: the system has no maintenance, 90% of escalators and access tourniquets are out of order, the trains don’t have air conditioning, some stations have no lightbulbs or even security personnel.

300 operators have resigned in the last three months. 17 more did it last week, while many others haven’t returned to work from December holidays.

That’s why most employees chose to quit after their years of service, give away the severance pack, leave the country “or simply sell coffee in the street.”

“They make more money that way,” says Wuilis Rodríguez, who started working in the Metro in 2006 and used to support Chávez. “But this Maduro, who worked in the Metro, is destroying all of the country’s companies.”

A sad end for Metro de Caracas technicians, who trained operators in Medillín, the Dominican Republic, Panama and other countries in the region and now, they don’t even want to report for work, squeezed by poor salaries.

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 22 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate