Elections: A Short-term Risk for Dictators That Can Have Long-term Rewards

One study shows that elections often create short-term stability problems for dictatorial regimes, but those that ride out the electoral wave end up even more entrenched than before.

Photo: RTVES, retrieved.

It’s the question that’s kept the Venezuelan opposition at one another’s throats for years: exactly what is the effect of elections held in authoritarian regimes? Do they destabilize them, or entrench them, or do they somehow do both?

Well, Norwegian scholar Carl Knutsen thinks he has some answers. After studying 259 autocratic regimes from 115 countries, Knutsen and his team argue that, although elections often destabilize dictatorships in the short term, those that weather the electoral storm usually end up stronger.

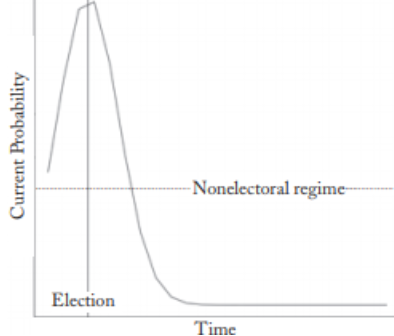

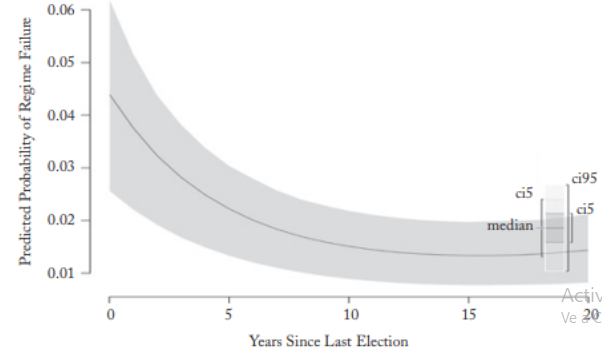

In a paper published in the journal World Politics in 2017, the team shows the probability of achieving regime change reaches a top in the months before and after the election, just to reduce quickly thereafter, ending at a lower level than it was in previous years.

Probabilities of regime breakdown before, during and after an election. Predictive probability of regime failure depending on the years after the election, based on a generalized additive model (GAM). Taken from Knutsen, C., Nygård, H., & Wig, T. (2017). Autocratic Elections: Stabilizing Tool or Force for Change? World Politics, 69(1), 98-143.

The team offers some informed speculation about why this could be: perhaps election years allow opposition groups to coordinate collective action against the government, increasing the chance of a breakdown, which increases the chances of short-term democratization. But the window of opportunity is limited.

Elections create an occasion to call for rallies and public events, which can be used to show a group’s strength to the country. Furthermore, a poor result or low turnouts in an election, specially if it’s rigged, can send signals of government weakness to key figures of national and international groups, lowering the cost of defying the regime and creating a focal point for change. Actually, 35% of all regime breakdowns studied occurred during election years, even though these represented only 10% of the total 4,000 autocracy-years collectively studied.

Elections are the hallmark of the free world, where bad governments are peacefully removed and good ones rewarded. You certainly can’t have a democracy without elections. But increasingly, practice show you can’t have a dictatorship without them, either. As Venezuelans know, autocratic regimes like to hold elections from time to time (and brag about it), even though they may pose a threat to their immediate stability. Their long-term benefits surpass the short-term risks.

In Venezuela, even though elections have generally taken place without major incidents, most protest cycles in the last 20 years have been related to them: the student movement against the Constitutional amendment of 2007, the 2014 protest cycle following Nicolás Maduro’s disputed election; the 2017 protests were ignited because of disrespect to the 2015 legislative election, and the regime’s refusal to hold a recall referendum.

You certainly can’t have a democracy without elections. But increasingly, practice show you can’t have a dictatorship without them, either.

The statistical models used by Knutsen, suggest that the risk of regime breakdown is five to seven times higher during an election year than five years after it, although it’s clear that an electoral defeat of the autocratic regime is, by definition, unlikely. This is of little relevance, since the election doesn’t produce the breakdown by itself, but rather creates favorable conditions for power groups in or outside the country to make it happen. The election, then, is not an end, but a means.

The Venezuelan opposition seemed to at least grasp this idea in 2017, when, after the sham National Constituent Assembly election, many opposition figures started selling elections as an end rather than a means. The objective was no longer to protest the government, but to put an irrelevant politician in an irrelevant post, claiming that a victory would be a critical hit for the government, without explaining why.

Now, regimes whose income comes directly from natural resources usually find it easier to monopolize state money. This, along with large, committed military forces, can help them ride the initial storm and overcome the turmoil caused by an election’s aftermath, as effectively happened in Venezuela. In this scenario, regimes are likely to consolidate power, since elections favor its long-term capacity to control threats.

Elections provide information about opposition strongholds, allowing the regime to use targeted repression and redirect the distribution of scarce goods and services to areas electorally favorable, enhancing political segregation. The regime gets to test its organizational capacity, giving it a chance to improve communication and action strategies with its allies, something that can be later used to repress dissidence. A minimally credible electoral process can also reduce international pressure on the regime, a trick that served chavismo for years, until fraud became impossible to hide.

It’s evident that the Venezuelan government has successfully exploited most of these long-term benefits—one of the keys to Chávez’s ascension was his manipulation of democracy to gain absolute power. But the government knows elections can be dangerous, too. They only hold them when they know they have the upper hand. Only after four months of protests failed to break its command line, the government dared to hold elections in 2017. Elections are a bet for autocrats but, as Knutsen’s study suggests, many times they miscalculate, and the election does create a wave of public outrest too big to surf.

Several opposition figures have been trying to sell January 10 (when Maduro will take office after an election universally seen as fraudulent) as the new focal point to put new pressure on chavismo, but we all must start seeing elections as what they are in this context: neither key, nor useless. Voting or not voting may be utterly irrelevant, but organizing and mobilizing around these events may be our only chance to put some domestic pressure on this autocracy, and tip the scales.

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 21 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate