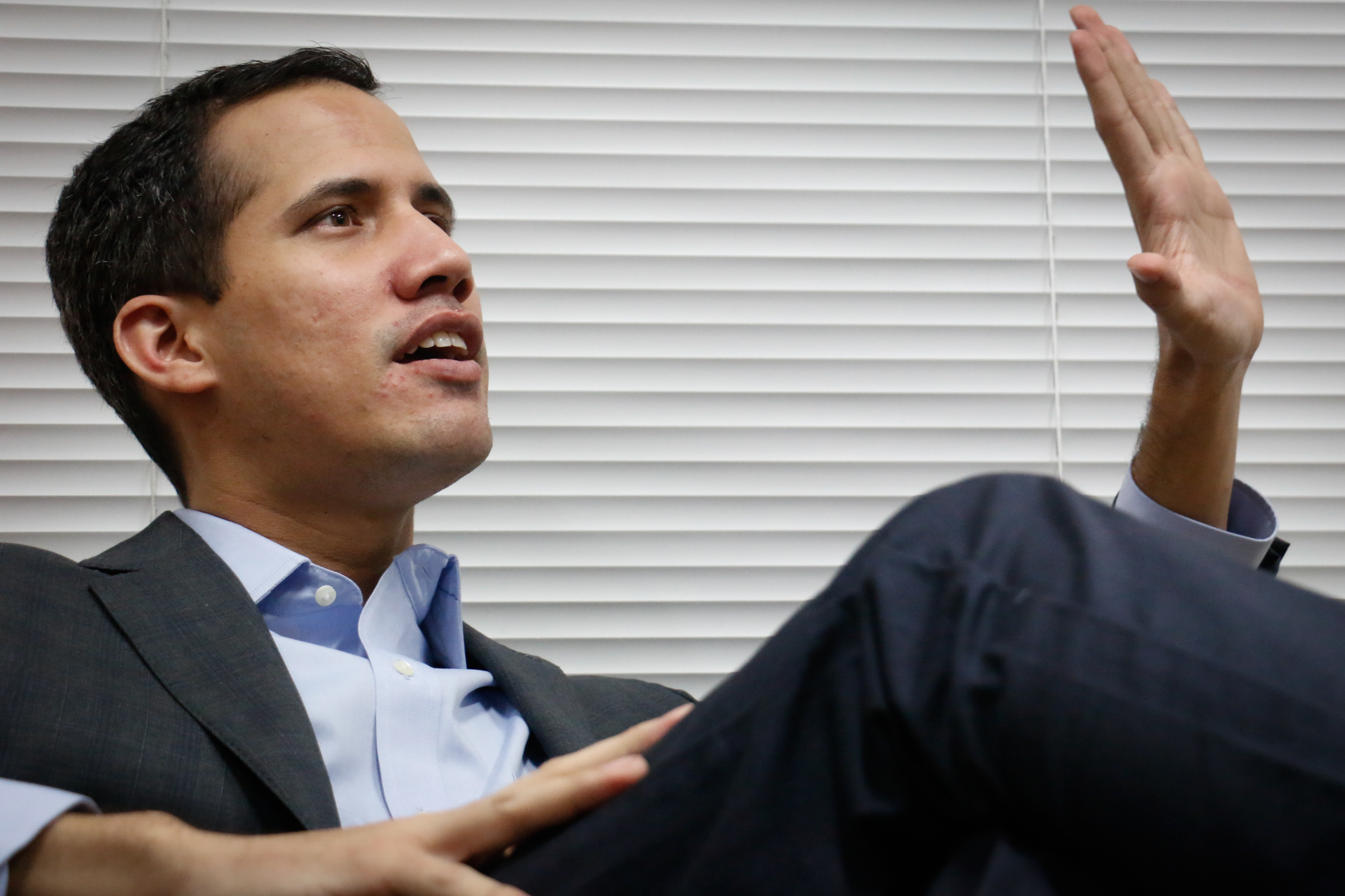

Guaidó Talks About The Thorny Challenge He Faces

History placed Juan Guaidó on the forefront of the Venezuelan opposition. He wasn’t looking for that, and we couldn’t have foreseen it. I talked to him about the challenge of fulfilling sky-high expectations while making sure others don’t sneak ahead of him in the final lap.

Photos: Daniel Hernández

Juan Guaidó admits to carrying a historic burden on his shoulders. He says so when carefully answering each question, quickly looking at his colleagues in the National Assembly Board. The AN Speaker is in the spotlight. A part of the country sees him as the white hope of transition, the liberator that can break the chains of chavismo, the impetuous young man who, up until a few days ago, was a second rank in his party’s leadership—at best—and now heads the only state power recognized as legitimate by the international community, business sectors and other actors of society not controlled by PSUV.

His challenge is huge. Not only must he navigate murky waters of opposition grinding, which devours any leader who fails to fill the expectations of a very active society—Henrique Capriles and even Miguel Pizarro suffer from this nowadays—but also handles the pressures of various groups that fancy themselves “on the right side of history.”

And Guaidó knows it, every time his phone rings, at least before SEBIN officers took it away when they detained him on Sunday, January 13. “He gets a ceaseless stream of messages telling him to do this or to say that. It’s nonstop,” says a lawmaker who’s witnessed the endless ringing of the 35-year-old Vargas politician’s mobile.

Guaidó sticks to one plan: we must end the usurpation of Miraflores, achieve a transition government and give way to free elections.

Guaidó sticks to one plan: we must end the usurpation of Miraflores, achieve a transition government and give way to free elections.

“I suggested he should uninstall Twitter,” another deputy adds. “For one, he has to deal with the most radical lot, those who say he has to claim the presidency.” Meanwhile, there are those who insist that he must take a more measured and strategic approach. That’s the one he’s chosen, for now.

Guaidó sticks to one plan: we must end the usurpation of Miraflores, achieve a transition government and give way to free elections. “The most important element is to gather the necessary strength to put an end to the usurpation. Our role, our challenge, is to rally all sectors of society, including the Armed Forces, to accomplish that.”

He announced that plan on January 5, and it’s been gaining traction as the hours pass. That’s why he spoke of “taking charge” six days later, and the idea that he’s “the president of all Venezuela” came two days after. Step by step, he’s drawing nearer. Of course, he knows he has to reach different audiences. “We live in a dictatorship, and for the transition we need everyone, including chavismo, those who have deserted and those who remain, in fear of speaking openly because they have nowhere to go.“

He says he wants to give them a way out. That’s the goal of the amnesty approved by Parliament. Article 3 of that text says: “All constitutional guarantees will be granted in favor of any civilian and military officer who, acting in compliance with articles 333 and 350 of the Constitution of the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela, cooperate in the restoration of democracy and constitutional order in Venezuela, violated by the de facto regime who is now usurping the Presidency of the Republic.” The amnesty would also erase any stain since 1999. A new beginning.

It’s part of the incentives for those who want to split from the ruling clique headed by Maduro. But those are still messages to the wind, for now. Who in chavismo could we negotiate with right now? “I’m not sure, to be honest,” says Guaidó, who also admits that he still doesn’t have any direct contacts in the barracks.

Guaidó, however, isn’t alone. In the black swan roulette, everyone seeks his niche. Rafael Ramírez, for example, tells Tal Cual that “Maduro knows chavistas are going to oust him from power and I’m going to lead that chavista option, it will be a civilian-military option.” He goes even further: “I think I’m one of the few in the Venezuelan political sphere who has the capacity to rally military support.”

The AN Speaker is in the spotlight. A part of the country sees him as the white hope of transition, the liberator that can break the chains of chavismo, the impetuous young man who, up until a few days ago, was a second rank in his party’s leadership.

The AN Speaker is in the spotlight. A part of the country sees him as the white hope of transition, the liberator that can break the chains of chavismo, the impetuous young man who, up until a few days ago, was a second rank in his party’s leadership.

The man who was once called “the Tsar” of PDVSA in Hugo Chávez’s times, says that he’s the right person to recover the country and even outlines a plan that includes releasing political prisoners, restoring political rights and renewing powers.

Of course, Ramírez bears the mark of chavismo and a bunch of corruption accusations, including having allowed his cousin to get rich with PDVSA contracts. On the other hand, Juan Guaidó looks clean. He has an advantage in his freshness: he’s so new, so unprecedented, that nobody has really dug out a story about him.

Polling agency Delphos confirms that his impact on public opinion was minimal at the start of 2019: he didn’t even appear among the spontaneous mentions of leadership. After January 5, things changed, although not immediately. His public impact is growing, like a snowball effect. After all, Venezuela is a country under the regime’s communicational hegemony, without mass news outlets or TV stations ready to broadcast his swearing-in ceremony in Parliament, with blocked digital news pages (El Pitazo, La Patilla, Caraota Digital, El Nacional, just two mention four censored by CANTV) and an important decline in social media users.

That last refuge is actually more and more vacant. According to official data by the National Telecommunications Commission, the country lost 8.8 million mobile subscribers since 2014. After having a mobile penetration of 102.6% during the last quarter of 2013, it now stands at 69.8% in the first quarter of 2018. The country went from having more mobile lines than people, to the point where at least 30% of the population doesn’t own any. Additionally, internet penetration went from 62.43% to 60.76%, although Conatel’s report doesn’t consider migration, but the population estimates of the National Institute of Statistics (INE). ADSL internet subscribers went from 19,453,242 to 18,108,335, a drop of over 1,300,000 contracts. The causes: the economic precariousness to supply users and providers with equipment, as well as a diminished capacity to replace stolen or broken equipment.

And in the barracks? Do soldiers read his messages, his speeches, his phrases?

In his public speeches, Guaidó has asked everyone to spread the word, to replicate the message. One of his aspirations is that this might allow him to reach a critical mass and build momentum for January 23, when popular mobilization might flood the streets again. That will be the start of the second chapter.

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 22 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate