Airport, Unplugged

I was supposed to go back to Ecuador. But instead of going to the airport and saying goodbye—for now—to Venezuela, I ended up in the midst of the consequences of the second national blackout in 17 days.

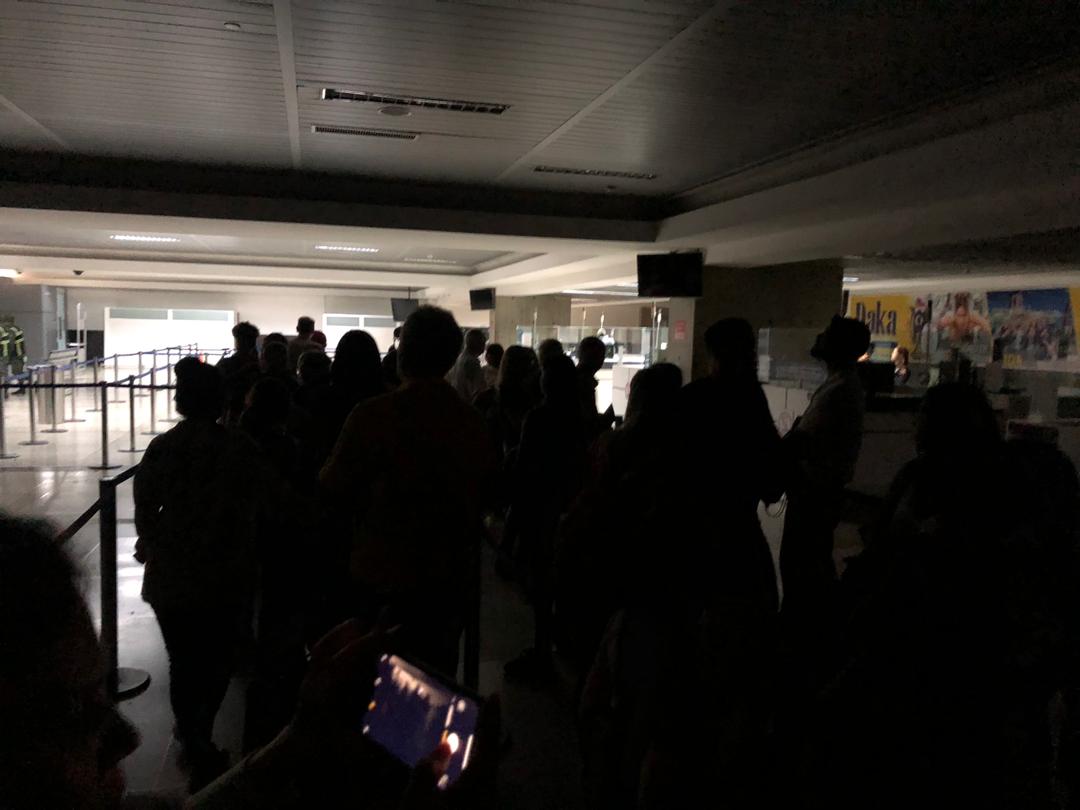

Photo by the author.

The moment we entered into the Boqueron II tunnel, the gateway to La Guaira, we knew.

Pitch. Black.

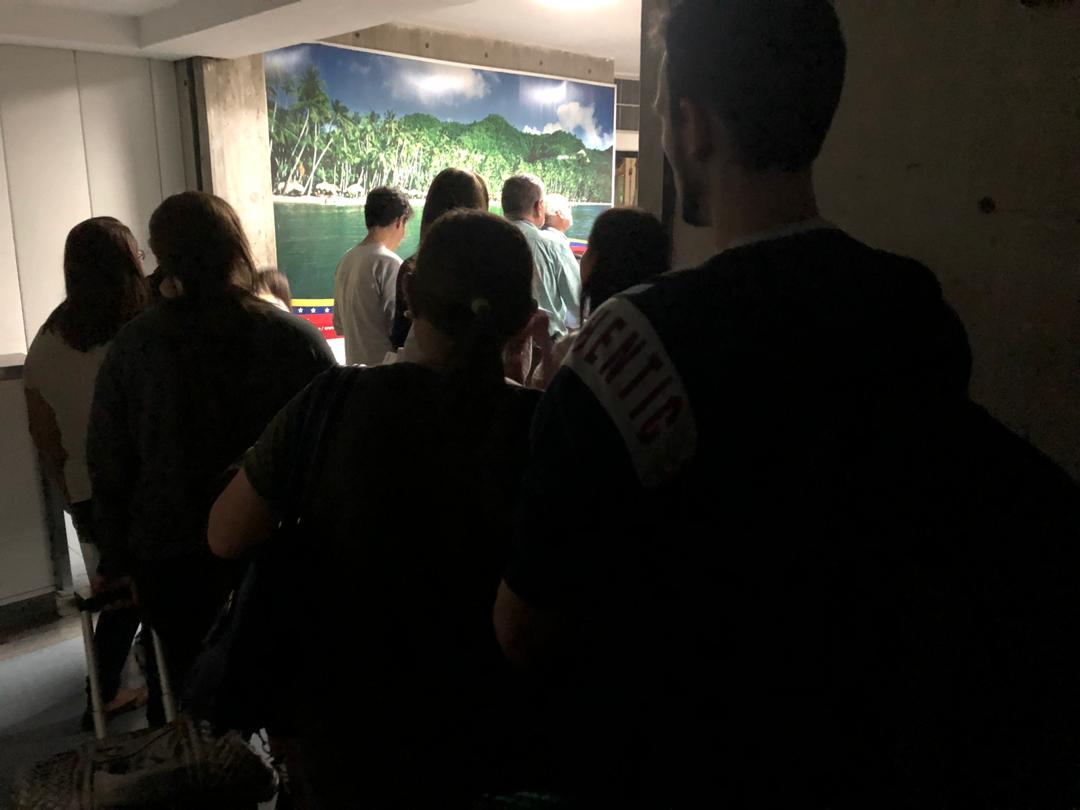

The social media-dependent Venezuelan diaspora developed a rite of passage: if you’re leaving the country, you take a photo of your feet stepping on the tiles of Carlos Cruz-Diez’s “Cromointerferencia de color aditivo,” the kinetic-art piece that illuminates the departures wing of the Simón Bolívar airport at Maiquetia. But no selfies were taken today, March 26th, because we’re experiencing the second nationwide blackout in less than a month.

Instead, the Caribbean heat and humidity took over the half-powered building. Lights were randomly on: some counters (with passengers waiting) had no electricity, neither did the restrooms, but Burger King and Papa John’s were open for business. You gotta keep those pizzas rolling!

The lines for checking in were three to four gates long. Iberia cancelled a flight to Madrid, and Estelar did the same with the New York route. People got to the airport at 5:00 a.m. for flights leaving at 7:00 p.m.; computer systems went on and off again. Half a dozen airlines decided to do the entire process manually, with pens and paper, leaving some passengers scrambling for their tickets saved on their phones.

“I have it, but there’s no cell reception here,” said a young lady at a counter.

“Well, go outside, look for it and come back.”

Last night, people were checking in with their cellphones’ flashlights. Today, a “contingency plan” was put in place. An X-ray machine and a baggage carousel were working. The WiFi was working (as well as Maiquetia WiFi can work). “The airlines were aware that this (a blackout) may happen again, so they were more prepared,” a source connected to the airline industry told Caracas Chronicles.

Among the shadows, lies the decay of what was a very active airport ten years ago. Since 2013, the majority of the international airlines flying to Venezuela stopped operating in the country, and recently, American Airlines also suspended their Miami-Caracas flights, with all the instability and the closing of the American embassy. Now, the Simón Bolívar airport is a place where a sicario can kill a passenger and leave on foot, the restrooms almost never have running water, and working A/C and luggage carousels are luxuries.

In the long line, a mother is dealing with her two kids. They were restless, and nowhere near the end. National Police officers were roaming the entire airport while wheelchairs were rolling to help the elderly after they’d been standing for hours. Others were trying to wrap their luggage in plastic, even with the machines not working. It was chaotic, something you’d find at the banana-republic parody video games Tropico.

At the domestic flights terminal, the scene was from Silent Hill. Only a few passengers were at Venezolana counter, while others asked at Estelar if they were gonna fly today. “Come back in 45 minutes to check if the system is up,” was the answer. People fell asleep under the blue or brown light of the stained glass on either side of the building. In the middle, workers were repairing the floors, the smell of fresh cement in the air.

In both sides, desperation was sinking in. Water was a valued commodity on the vending machines: Bs. 3,000 a bottle (or two bucks if you were out of Venezuelan cash, like 95% of the people there). Nobody knew if their flight was going to take off on time, or tomorrow. “All bullshit,” screamed out loud a gentleman in the Laser line, while talking about propaganda minister Jorge Rodríguez ’s intervention on national TV. “This is gonna keep happening, again and again. It’ll be the new normal.”

One mile away, at La Zorra beach in Catia La Mar, locals enjoyed the warm beach and blazing sun. “What else are we gonna do?” said a father of four, who even took the dog for a walk on the beach. The beach. The one place in my list I didn’t visit in my time in Caracas. As I dipped my feet and sunk my head in the warm water, the people weren’t worried if power came soon enough. “Now, we have el Caribe. We’ll worry if the light doesn’t come tonight,” one man told me, and then ran towards the sea.

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 22 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate