American Airlines Left Us Pretty Much Alone in the Dark

At first, it was temporary, but on March 28th American Airlines announced the decision to suspend all flights to and from Venezuela for good. Just how trapped Venezuelans really are?

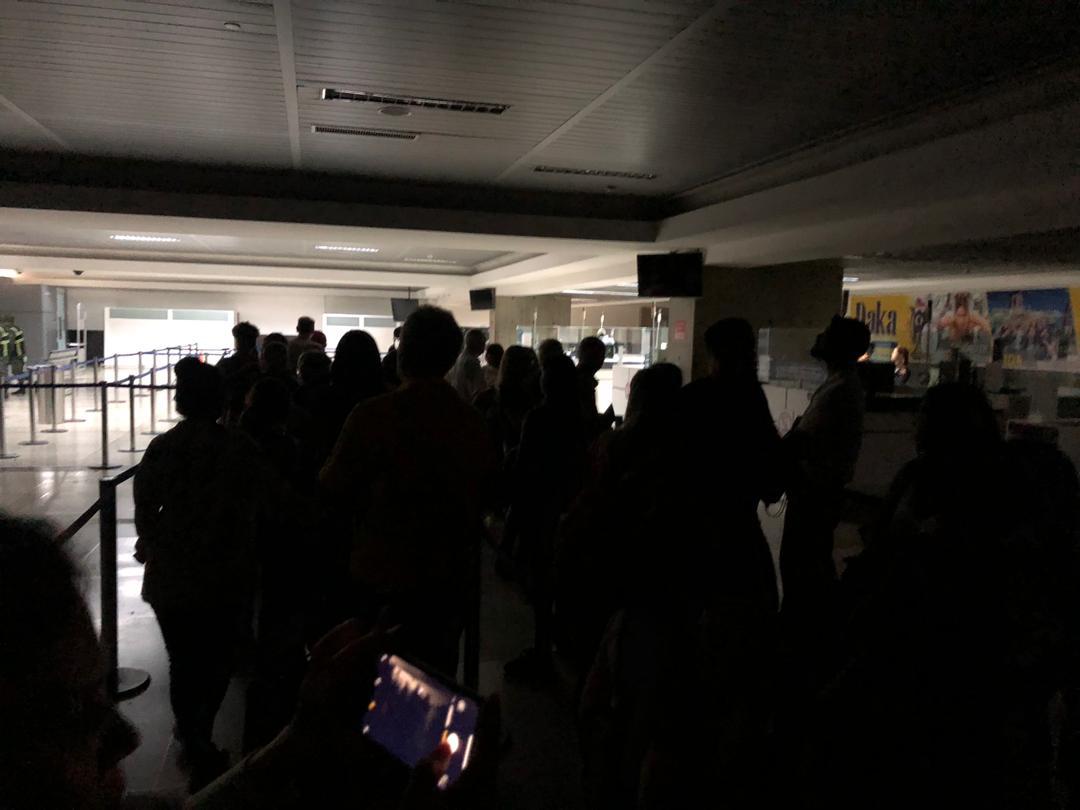

Photos: Toto Aguerrevere

American Airlines, the largest airline connecting Venezuela to the U.S., indefinitely suspended all flights to and from Venezuela last week.

“We never saw this as a possibility,” says Reinaldo Pulido, head of the Tourism Committee at the Venezuelan-American Chamber, and host of the radio show “Turismo en línea” on Fedecámaras Radio. “Airline activity is a sensitive area that depends on many factors. European airlines always have this option (to leave) because unions don’t want their crews spending the night in Venezuela. Now airlines make stops in the Dominican Republic and this is inconvenient in every way for the passengers and the airlines. Copa Airlines is also under attack, with a case that we hope the authorities don’t pursue, because the largest airline serving Venezuela with daily flights would have another reason to leave. Determining if American Airlines leaving will cause a domino effect, is really complicated.”

Reinaldo Pulido considers the nationwide blackout as the final blow for airlines, something that certainly was considered in AA’s decision-making process.

Reinaldo Pulido considers the nationwide blackout as the final blow for airlines, something that certainly was considered in AA’s decision-making process.

ast March, 11th, the U.S. State Department announced its withdrawal of all American diplomats from Venezuelan territory and, three days later, it also issued a travel alert, advising American citizens to refrain from traveling to Venezuela because of “crime, civil unrest, poor health infrastructure and arbitrary arrest and detention of U.S. citizens.”

Following suit, American Airlines’ pilot union pushed to suspend flights for security reasons, and the company complied, temporarily, on March 15th. Now all AA flights are suspended indefinitely.

Venezuelan airlines flying to Miami, like Avior and Laser, hire American charters to cover the route. These companies are solely focused on making money, so Pulido deems it unlikely that they cease operating, at least for now: “American Airlines had three daily flights from Venezuela to Miami, two from Caracas and one from Maracaibo. That’s around 450 seats a day, 15,000 a month.”

But American Airlines connected Venezuelans for 33 years to many other cities in North and Central America, certain parts of the Caribbean and even Europe, far beyond the coverage of national companies. All Venezuelans who still can afford to travel (and the Venezuelan diaspora) will be affected: to someone living in the U.S. or Canada, these changes are the difference between being on time for an ill mother and not being able to provide a life-saving assistance or saying goodbye.

Even though American Airlines didn’t transport cargo or those care packages sent puerta a puerta from the diaspora to their relatives here, everyone had at least one person they knew that was coming to Venezuela soon and could bring urgent medicine or medical supplies, diapers or baby formula. Pulido considers the nationwide blackout as the final blow, something that certainly was considered in AA’s decision-making process. In an airport where restrooms are always closed because there’s no water and every process has to be done manually, from check-in to immigration, it’s only natural that serious corporations ponder if it’s really worth it, going through all that trouble.

Jorge Álvarez, head of Ceveta, the Venezuelan Air Transport Chamber, said that 13 planes out of 115 were still flying, since the government wouldn’t provide dollars for the industry to buy the parts required, keep up with maintenance standards, and kept regulating tickets prices, making airlines lose money every time a flight takes off.

Jorge Álvarez, head of Ceveta, the Venezuelan Air Transport Chamber, said that 13 planes out of 115 were still flying, since the government wouldn’t provide dollars for the industry to buy the parts required, keep up with maintenance standards, and kept regulating tickets prices, making airlines lose money every time a flight takes off.

14 other airlines have also stopped operating in Venezuela during the past three years: Avianca, Delta Airlines, United Airlines, Dynamic Airways and Aerolíneas Argentinas, Air Canada, Alitalia, GOL, Tiara Air, Lufthansa, Aeroméxico, Insel Air, LAN and TAM (as Latam Airlines), almost all of them because the government owed them 3.7 billion dollars from the CADIVI era. To this day, international airlines haven’t received most of what the Venezuelan government owes them, two years after most of them left.

In February 2018, Jorge Álvarez, head of Ceveta, the Venezuelan Air Transport Chamber, said that 13 planes out of 115 were still flying, since the government wouldn’t provide dollars for the industry to buy the parts required, keep up with maintenance standards, and kept regulating tickets prices, making airlines lose money every time a flight takes off. A taxi from Caracas to Maiquetia airport, a 20-minute ride, can be more expensive than a domestic flight.

Now only nine international airlines continue to operate commercial flights to and from the country: Air Europa, Air France, Copa Airlines, Cubana de Aviación, Iberia, Wingo, Plus Ultra, Turkish Airlines and TAP. Other companies that Venezuelans had never heard of started popping up out of nowhere: Estelar, Eastern, Dynamic (active for a few months a couple of years ago) and Swift Air, covering Miami – Caracas, NYC – Caracas. The Simón Bolívar International Airport website is a mess, but it states that 15 international flights were scheduled to leave Maiquetia airport on March 29th, meaning there are more airlines and international flights departing from José Martí airport in Havana today than from Maiquetia the entire weekend.

Is it too late or too soon to feel claustrophobic?

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 22 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate