Pandering to the Imperial Left: The New CEPR Report

The new report by the CEPR, “Economic Sanctions as Collective Punishment: The Case of Venezuela” written by Dr. Jeffrey Sachs and Mark Weisbrot, is generating sympathy for the chavista cause in the liberal media at a critical moment, but it’s already being challenged by the heavyweights.

Photo: Global Citizen retrieved

Jeffrey Sachs can be criticized for many things. Although he has a long history working in international development and partnering with respected international organizations, his record is far from spotless: he managed the disaster of the post-Soviet transition to capitalism, and his Millennium Villages in Africa were a resounding failure, inspiring Nina Munk’s exposé, “The Idealist: Jeffrey Sachs and the Quest to End Poverty.”

And although his recent opinion piece for The New York Times, co-authored by Venezuelan economist Francisco Rodríguez, is intelligent and compelling, his report from the Center for Economic and Policy Research (CEPR) “Economic Sanctions as Collective Punishment: The Case of Venezuela” will piss you off.

First, a disclaimer: the report is published by the CEPR, co-founded by Mark Weisbrot, a guy that’s difficult for me to write about, given what I know about him (he’s also president of NGO Just Foreign Policy). For years, he denied there was any crisis in Venezuela. Now, with this study, Weisbrot teams with Sachs to unload much of the responsibility for the present Venezuelan crisis onto the shoulders of “U.S. imperialism”, specifically, on the Trump administration.

It is, obviously, very wrong and Harvard economist Ricardo Hausmann, and fellow economist Frank Muci, are here to demolish the foundations of the report.

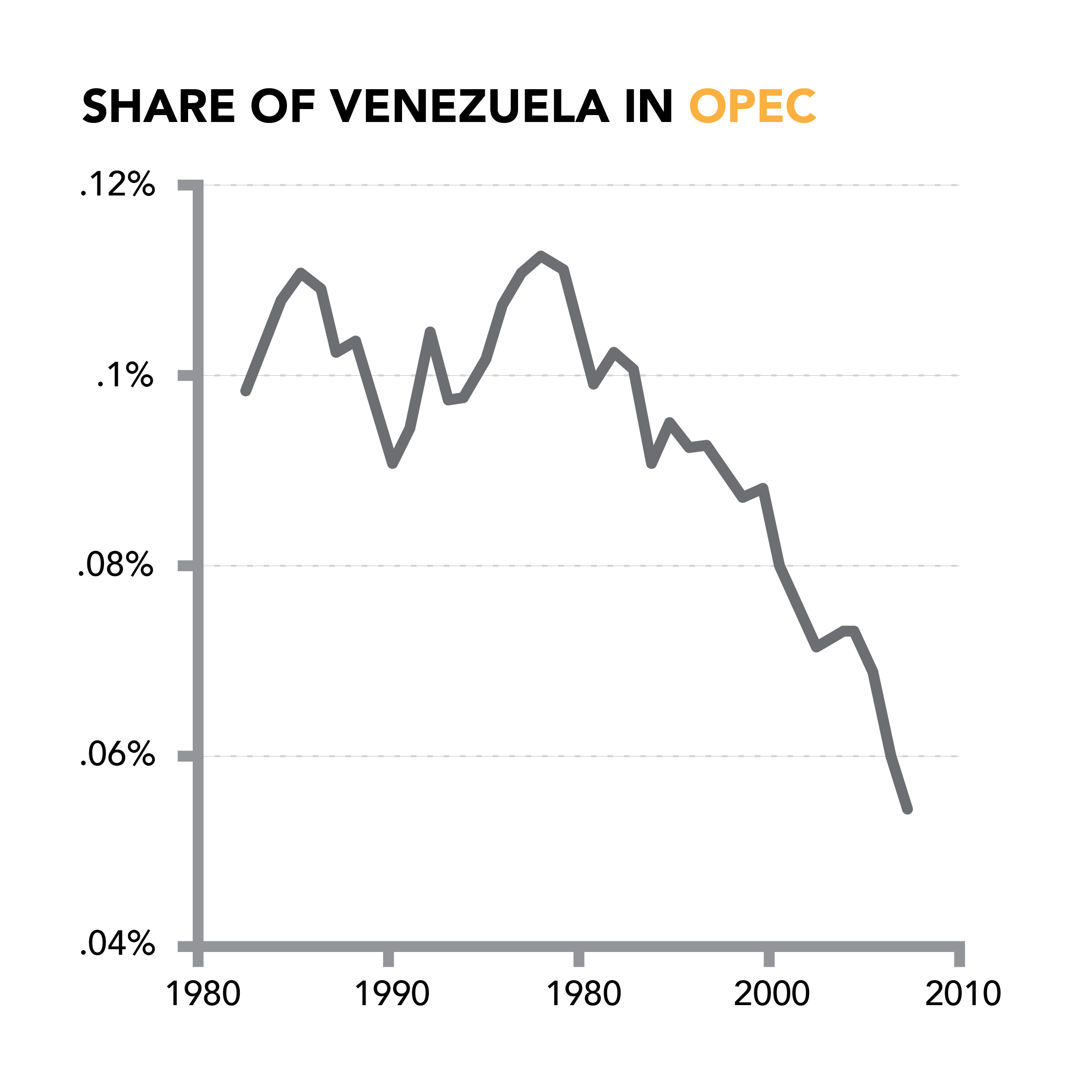

The Venezuelan scholars begin by pointing out the obvious: using “Colombia as a counterfactual for Venezuela” in an attempt to demonstrate how “Venezuela’s oil production trends were similar [to Colombia’s] before sanctions were imposed” is entirely off-base. The comparison of Colombia with Venezuela can help indeed, but in a different field (Venezuela’s oil production in the context of OPEC). They use this graph:

Venezuela’s oil production in the context of OPEC.

Venezuela’s oil production in the context of OPEC.

With that out of the way, they address the claims the CEPR authors make that 40,000 Venezuelans had died in 2017-2018 as a result of Trump’s sanctions: “How do they rule out that mortality rates wouldn’t have continued rising without sanctions? How do they rule out that it wasn’t the collapse in the imports of food and medicine that pre-dated the sanctions that increased death rates? Or Venezuelan doctors leaving the country? Or government indolence and corruption? Weisbrot and Sachs don’t rule out or address any alternative explanations.”

“Give me more money, I am a new man”

Here I have my own questions as Weisbrot and Sachs made, over and over again in different contexts throughout the report, the same argument with a deeply flawed underlying assumption; to wit, that the Maduro mafia would have used the new debt to restructure the old debt, or would have used the new debt to repair and fortify the economy, or buy medicines or food or any number of urgent necessities, rather than just robbing the money, as they’ve done for 20 years.

Hausmann and Muci remind us who we’re dealing with here; it was the Maduro government, they write, that “opted to cut food and medicine imports, triggering the humanitarian crisis well in advance of the sanctions. Consequently, by the time sanctions were imposed, Venezuela had already slashed imports of food and medicine by more than 80%… triggering a humanitarian crisis.”

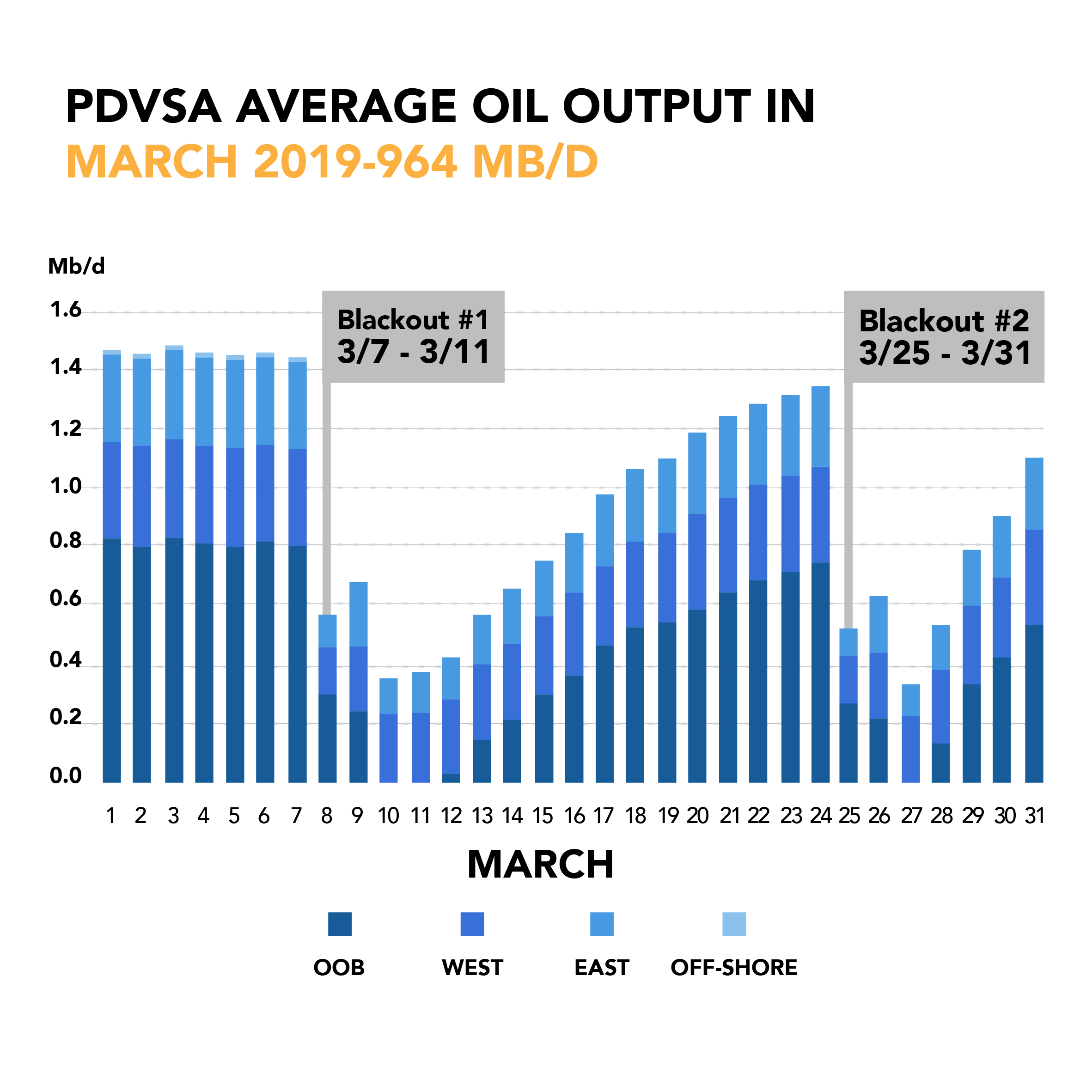

Well before U.S. sanctions, “Venezuela was already shut out of capital markets,” as a debtor who was “too risky to lend money at anything other than an eye-gouging rate.” The U.S. government sanctioned PDVSA in January of this year but, disagreeing with Weisbrot and Sachs (who directly attribute the decline of oil production to the sanctions,) Hausmann and Muci point out that oil production “declined precipitously” before the April 15th implementation of sanctions, and the decline is due to the nationwide blackouts:

The U.S. government sanctioned PDVSA in January of this year but, disagreeing with Weisbrot and Sachs (who directly attribute the decline of oil production to the sanctions,) Hausmann and Muci point out that oil production “declined precipitously” before the April 15th implementation of sanctions, and the decline is due to the nationwide blackouts.

The U.S. government sanctioned PDVSA in January of this year but, disagreeing with Weisbrot and Sachs (who directly attribute the decline of oil production to the sanctions,) Hausmann and Muci point out that oil production “declined precipitously” before the April 15th implementation of sanctions, and the decline is due to the nationwide blackouts.

Of course, Weisbrot and Sachs tell us that “the sanctions have also contributed substantially to the length and economic damage of power outages, including the severe electricity crisis in March,” without offering any evidence to back that statement up. Indeed, the lack of maintenance and investment in the Guri dam goes unmentioned in the CEPR report. Instead, it claims that “sanctions have limited Venezuela’s access to diesel fuel” for thermal electric plants without explaining why a petro-state would need to import diesel fuel.

Hausmann and Muci pick up on this and discuss the earlier (2007 and 2009) “corruption orgy” around the “electrical emergency,” when $50 billion disappeared without adding “a single gigawatt” to the electrical grid. Their conclusion is worth quoting in full: “Perverse policies and extreme mismanagement explain the bulk of Venezuela’s collapse. The financial sanctions have prevented the regime from further mortgaging the future of the country. They are means to put pressure on the regime to negotiate the return to democracy and constitutional rule. Oil sanctions are designed to restrict their access to the resources with which to continue its oppression. Nobody disputes that they will adversely affect PDVSA going forward, but they have brought Venezuela closer than ever to regime change. It’s understandable if the authors don’t agree with the use of sanctions to pressure Venezuela’s dictatorship. It is not understandable that they would misrepresent their effects with sloppy reasoning.”

The economic disaster that fell to Earth

There were a few other points about the CEPR report that Hausmann and Muci didn’t discuss. In the “Executive Summary,” we find this stand-alone statement: “The sanctions reduced the public’s caloric intake, increased disease and mortality (for both adults and infants) and displaced millions of Venezuelans who fled the country as a result of the worsening economic depression and hyperinflation.”

How is it possible that there’s no mention of the wild emissions of currency by the Maduro government, and the years of economic policies that caused the depression and hyperinflation?

Then they tell us that “the sanctions implemented in 2019, including the recognition of a parallel government, accelerated this deprivation and also cut off Venezuela from most of the international payments system, thus ending much of the country’s access to these essential imports including medicine and food.” In what way do the writers consider the “recognition of a parallel government” to have “accelerated this deprivation”? Is this a simple gratuitous piece of political propaganda wedged into their report?

There’s also that “international payments system,” which the Venezuelan government is notorious for not using. Suppliers often go for years not being paid, which is to say that when the Venezuelan government had access to the “international payments system,” it didn’t use it; certainly, at least, not to pay its debts.

W&S also say that “the unilateral sanctions imposed by the Trump administration are illegal under the Charter of the Organization of American States (OAS).” The fact is that the sanctions imposed by the United States were rather a response to ongoing calls from the opposition to put economic pressure on Maduro and to prevent him and his cronies from further pillaging of the national treasury, precisely through such debt restructuring. Intellectuals of the Venezuelan opposition began making calls for sanctions to Mercosur in September 2016, but those calls went out only after the Secretary General of the OAS, Luis Almagro, threatened the Maduro government with the “most drastic sanctions” to be taken by that and “other regional and sub-regional organizations” if the recall referendum wasn’t allowed to go through.

So Weisbrot and Sachs might have difficulty explaining how these sanctions violate the OAS charter when the Secretary General himself initiated the call for those very sanctions.

The following year, after the MUD opposition called for the U.S. to impose sanctions when it was clear the referendum wouldn’t be allowed, the EU came on board with its own call for sanctions. It urged the imposition of “selective instruments of pressure that wouldn’t affect the population so that the Venezuelan government would return to the negotiating table.”

By now, the reader should get the picture. Hausmann and Muci were kind in referring to the “sloppy reasoning” of the report. The work of Weisbrot-Sachs, in fact, turns out to be a crude piece of gringo-chavista whitewashing aimed at gaining sympathy for “the cause”. They even use the falsified reports of UN officials who are on the payroll of Putin. You can “miss” the CEPR report without any regrets, and if you want to know about the U.S. sanctions on Venezuela, you should read César Crespo’s excellent review. He’s not trying to cover for anyone. He’s just telling it like it is.

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 22 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate