The City That Won’t Die

This is a celebration of the spirit of a place where people insist on going out at night, amid many real dangers. This is a celebration of Caracas.

Photo: Agente Extraño live, by the author.

I first noticed it about a year ago, when we were due to play at Suka’s new space, Íntima, a spot for live shows of all kinds. We had to go on stage at 9:00 and, at 8:45, there were like eight people waiting for us. It looked like a dud for a show that both the band and the venue promoted like hell, and we all decided we’d go live at 9:30, with whatever crowd we had by then. With low attendance, your payment goes down, but so do pressures. I figured I’d take this for what it was and enjoy my time playing in such a nice place.

Between 8:45 and 9:15, some 30 people showed up and they kept coming. You could hear it from the backstage, a growing hum of voices and laughs, the classic soundtrack of nightlife. Minutes decided to move at snail pace and what the experts call “performance anxiety” went through the roof. I went for Carlitos, our manager and rhythm guitar.

“Let’s step outside for a bit,” I say, sorta freaking out.

He nodded and out I went, unprepared for what we were about to face.

If you’re a real outsider to Caracas’ urban culture, Suka is one of the most famous nightclubs at a pretty popular mall, Centro San Ignacio, which goes from a corner to the next full of clubs for you to drink and dance, not quite like Miami Beach, but that’s its general principle. And there we were, the only two guys over 30 in a never-ending stream of kids in clubbing outfits. I’ve never been one to go out at night very much (my version of a night party involves more Dungeons & Dragons than reggaeton) and given how all of our previous shows were played with daylight, I lived under the impression that nighttime Caracas was an outland ruled by crime, shadows and silence.

Reality destroyed the myth. Shouldn’t all these kids be home, safe from what goes bump in the night?

Apparently not. They own the night.

Underground clubbing

“I wouldn’t say Caracas’ nightlife is dead,” Carlitos told me last Saturday, when we were about to play at the still alive-and-kicking Moulin Rouge club, a living fossil of the 1960s’ Sabana Grande bohemian scene. “I’d say it’s embarrassed to survive.”

And he should know: Carlos Ramírez has been a fixture of our musical scene since 2011, when he decided to stray away from his daytime job at engineering. A concertgoer, promoter and musician, the guy has gone in some (or all) of these capacities at Doors, Espacio, Discovery Bar and the Moulin Rouge, iconic clubs of the Venezuelan capital. Tonight, most of those places have shut down.

Curetaje at the Moulin Rouge. Caracas, 2019. Photo: Jonathan Sujú.

“Going out at night today has the risks that you’d expect,” he tells me, “but there’s a need both to make art, and to go clubbing. Of course there’s a huge difference in attendance; four years ago you’d have 300 people a night at the Moulin, today 150 would be good.”

That Saturday, the crowd for us wasn’t huge, consisting mostly of loyalists and friends. Going out to the avenue of what used to be one of the hottest spots of the city, there’s a contrast with Suka a year ago. The street isn’t packed with night wildlife. There’s people looking for a party and the salsa clubs around us have open doors blasting with cymbals and piano, but let’s just say that if you arrive at midnight, you’re still going to find a parking spot.

“This has to do with money and the zone,” Carlitos explains. “First, we’re away from payday; the best time for a gig is immediately after folks get paid. Second, we’re in the border between Sabana Grande and Plaza Venezuela, which has a reputation for getting ugly in the wee hours. Even with money in their pockets, people respect that a lot. Of course they’ll still go clubbing, but they retire early and areas considered ‘safe’ have more crowds than places closer to downtown Caracas.”

Other dynamics apply: “If someone who left Venezuela comes back today looking to see a show, the first thing he’s gonna find is a lot of tribute bands. The big, famous artists aren’t coming anymore, and people with a thirst for the music they like go out looking for that familiarity. You can have two shows, and the one playing originals will have a smaller crowd than the tribute band. There are even tributes to Venezuelan bands, those who made it big and left, and this is regardless of genres and styles. There are tributes to Chino and Nacho, for example.”

“Someone who left five years ago wouldn’t recognize any of the names (or the clubs) of tonight’s Caracas,” agrees Ana Luisa Ces.

A comedian with a zillion of shows under her belt, it’s pretty hard to not like Ces when you talk one-on-one with her, something that undoubtedly helps her with crowds. Better known under the moniker of “La Señora Ana,” she replicates Carlitos’ opinion on her field.

“What I’ve noticed is that ‘Caracas by night’ has peaks and depressions,” she tells me over coffee. “In the old days, you had a show at La Quinta Bar (a pretty big night club at Eastern Caracas) and the place was packing, a night-long affair. Now, only one floor gets full and you must go on early, because people wanna go home early, there’s less of a will for all-nighters.”

“However…” she raises her index, “there are many comedians out there, lots of people putting up a show.”

Variety is the name of the game. While many of the local big comedians like Nanutria, La Nadia and Led Varela aren’t in Venezuela anymore, those spaces are occupied by others who quickly build up a following—like herself, or well-known comedian José Rafael “El Profesor” Briceño.

“The night scene has transformed and, in some aspects, diminished,” says Ces. “But it’s far from dead.”

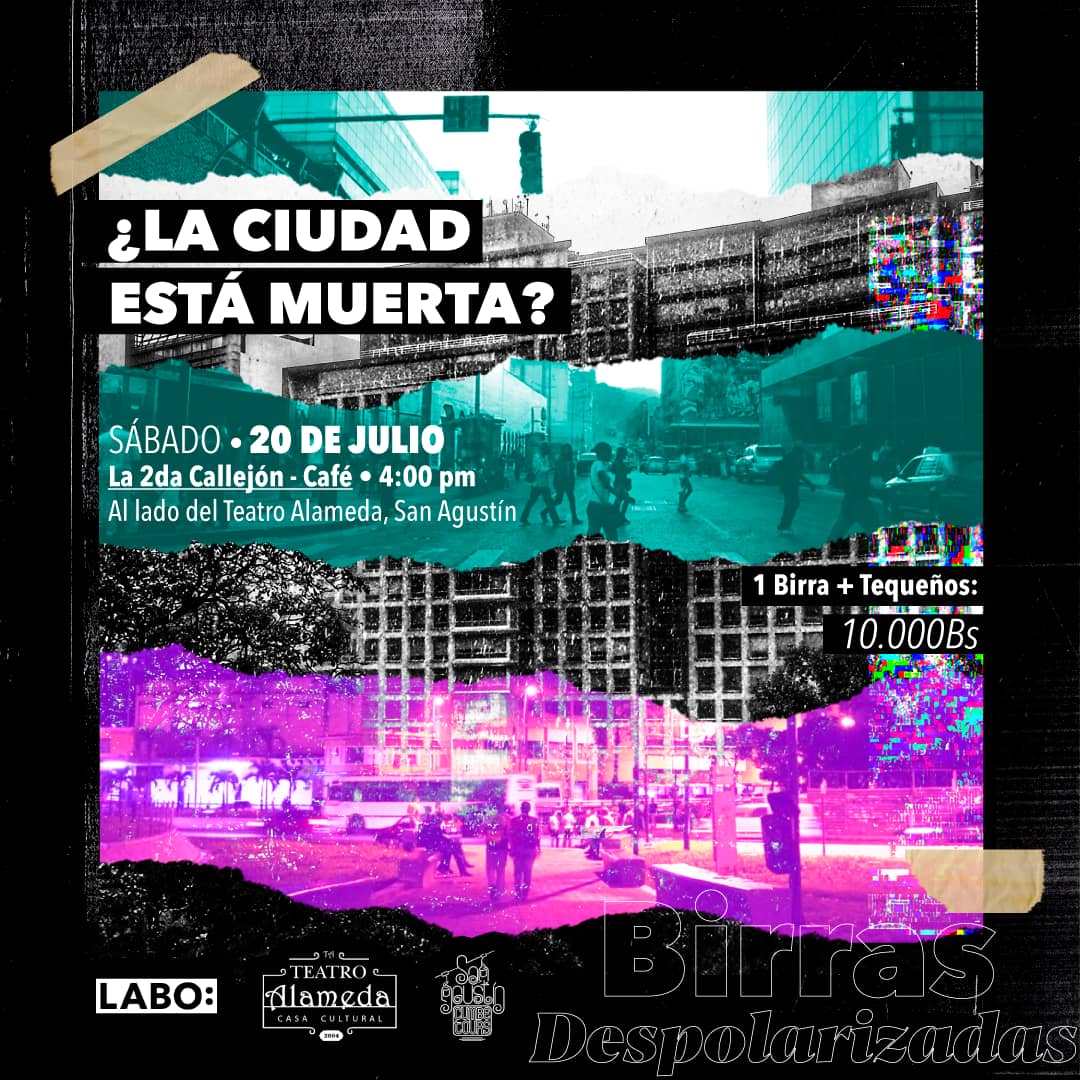

Flyer from music event “Is the city dead?”. Caracas, 2019.

The cogs in the machine

“People want to be part of the city’s transformation, they just need a helping hand.”

Ana Cecilia Pereira belongs to Ciudad Laboratorio, a group of activists bent on retaking the night. Just in the last couple of months, they’ve set up festivals of sorts in Chacao and Bello Monte, two corners that, okay, are in Eastern Caracas, but they also get vibrant in a city that’s supposed to be deadly afraid.

Bello Monte in particular feels today like the city that could be: I went a couple of weeks ago for an afternoon talk on the European architecture of the area—it was right on the street and there were, like, 20 people. But as the day turned into night, new nightspots like Java’s Café, El Farolito and La Castela bloomed with music and light, bands of all sorts playing live for actual crowds, with backgrounds of dance or film projections right on the buildings’ walls.

I bought a beer and sat on the sidewalk with my friends, feeling like I traveled back in time to those days in 2008 when things weren’t as messed up and people dared to go out. A town owned by its citizens, not by fear.

This was exactly the effect that Ciudad Laboratorio was looking for.

“We started a ‘Caracas by Night’ observatory last year,” Ana Cecilia says with her contagious energy. “We decided to carry out actual research and a method as scientific as possible to get a clear view of what was happening in our city when the sun went down, and how we could improve our quality of life. We wanted to be active observers.”

“On the first stage of that observatory, we considered illumination, transport, security and the natural flow of people in 31 public spaces of the capital. The first three elements turned out to be key. If a spot had access to public transportation, for example, turnout was bound to be high. The second stage had us at 8:30 pm in subway stations of areas with a well-known nightlife: Petare, Chacao, Chacaito, Bellas Artes and Plaza Sucre. We wanted to measure the flow of people, but we also needed to talk to folks and know where they were coming from, and what was their destination.”

Spontaneous crowd at a live show in Bello Monte. Caracas, 2019. Photo: Ingrid Ruiz

Judging by their results, Caraqueños get together in each other’s places and they do pull all-nighters, but in this context where they feel safe.

“That’s why we did a live event in Colinas de Bello Monte, ‘Ilumina.’ It was a bet to see if people would join in the reactivation of Caracas, provided they had a safe space. It was a total success, bigger than we expected.”

And it’s one thing to read it and quite another to live it. This weekend, Bello Monte will have Nocturneando, another festival summoning our will to defy our survivor’s guilt. If it is anything like the previous editions, you can expect many clubs with live music, food trucks, art galleries open with live performances, and artists of a Caracas’ scene that’s more underground than ever. In the 80s and 90s there was at least an artistic infrastructure with big-name promoters celebrating shows; now, it’s all a bunch of do-it-yourself activists and artists that get no mass publicity, but they create magic bubbles inside the tragedy.

I once read that “living means more than surviving,” and if that’s true anywhere, it’s in the night of a city refusing to die.

My toast to you, Caracas.

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 22 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate