Jail and Comedy In El Paso, Texas

We already know that the Venezuelan comedian just spent two months in jail. What we don’t know is the story of what happened in there. Here it is.

Photos: Raul Stolk

He was in the middle of nowhere, not knowing where to go. No phone, no money, no shoelaces. A police officer gave him a ride from the ICE processing center to a nearby gas station. Upon arriving, the owner, a Mexican woman, gave him a slice of pizza and allowed him to use her phone.

José Rafael Guzmán spent two months jailed in Hudspeth, Texas. Sooner than later, he says, the reasons why this happened won’t be reasons anymore. He talks without pause, a thousand stories pounding inside his chest, his neck too thin to let everything out at once. But right now he is at a point where he must abide by something that goes far beyond common sense: he must do as his lawyer says. There are a couple of funny moments during the conversation, but he’s generally introspective, serious, narrating in quick sentences. Not what you’d expect from this particular comedian.

José Rafael Guzmán spent two months jailed in Hudspeth, Texas. Sooner than later, he says, the reasons won’t be reasons anymore.

The story begins a couple of months ago when José Rafael was making a life-long dream come true: a road trip across America. He stopped in cities and towns, shooting content for Comida, Calle y Comedia, his YouTube channel. Earlier this year he shot Caminantes, a web series that featured him joining a group of migrants in Colombia, alongside Silvia Baquero, his producer, to document with humor the Venezuelan migration crisis. This time, the pair was taping José Rafael’s encounter with American culture, the deep, real America. In Philadelphia, he climbed the Rocky steps, crying after reaching the top. In Los Angeles, he visited Schwarzenegger’s star in the Walk of Fame. Rocky and Arnold are an inspiration for everything he does: “I was raised in a home without cable.”

They successfully finished the tour and ended on a high note by visiting a cannabis farm in California, where they shot some footage. José Rafael advocates for the legalization of marijuana and, it’s no secret, he’s an avid enthusiast of its recreational use.

Me no English

On August 12th, the day of his last Instagram post, Border Patrol officers stopped him at a checkpoint in El Paso, Texas. At first, he thought it wouldn’t be that big of an issue. Then the officers cuffed him and took him under custody.

Silvia was instructed to call Oswaldo Graziani, one of the founders of Plop! (the agency behind El Chigüire Bipolar) and José Rafael’s close friend, and ask him for help to get a lawyer. Between Silvia and Oswaldo, they came up with a strategy to infiltrate certain El Paso socialite circles to find the best lawyer possible for Jose’s case —this is a whole story in itself. And they found the man: Jeep Darnell, a young lawyer, built like a quarterback, with a hat and cowboy boots and a shiny belt buckle. Texan, very Texan, and truly pragmatic and open-minded. “What’s happening to you is something that has happened to every rockstar,” he told José Rafael in their first meeting.

He could pay 10 % bail, which in this case was $300 and be released immediately. But if he chose that option, since he was a tourist, they’d probably hand him over to ICE and he would be deported. And not to Mexico, where he had been living for the last few years, but to Venezuela. And that’s not an option for him: Venezuelan authorities didn’t only censor his radio and TV shows, but there’s also an arrest warrant against him for “inciting hate.” In a nutshell, the Venezuelan regime is after him for doing comedy.

The lawyer’s recommendation was that he remained in prison for the entire process. Jeep was optimistic, he was sure he’d walk free of charges, but he was also very clear: best case scenario was a month, the worst-case scenario was six. José Rafael almost had a heart attack: “Don’t worry about the legal part, we’ll take care of that. Leave it to Oswaldo. You worry about being OK in here, because you’re going to have a bad time.” Double heart attack.

After the process of admission, he was taken to Hudspeth County Jail. A forsaken town two hours away from El Paso, where everything revolves around the prison. This prison wasn’t like what he had seen in Nat Geo documentaries. It was a small prison, for a temporary stay, where inmates don’t spend more than a year. There was, however, a varied representation of criminals, covering a broad range of crimes, races, and affiliations.

“I have to clarify something here,” says José Rafael, “I didn’t speak a word of English. It’s not something I am proud of, obviously, but it is what it is. It’s like they were speaking German. So, after they searched me, the guard, who was an old man whom I couldn’t understand, starts saying ‘foot up, foot up’, and I didn’t get what he meant. And since I was naked and I’d been searched everywhere, I assumed there was only one thing missing. So I bent over and opened my buttcheeks. The old man started yelling like crazy ‘feet! feet!’ and then I got it. What he wanted was to check the soles of my feet.”

The shoes he wore in El Paso, free and with shoelaces. Photo: José Rafael Guzmán, 2019.

He was given a uniform with black and white stripes and they took his shoelaces—part of the protocol so prisoners don’t hang themselves. And from there, he was taken to a cell with seven people. Four bunk beds, one WC, all of it in 3×7 square meters.

Prima Nocta

The first test of character took place on the day of his arrival, when one of his cellmates grabbed him from behind with the shower curtain. He embraced him tightly, measuring how strong he was. José Rafael wrestled himself out and pushed him how he could. The guy laughed mockingly and told him he was kidding. “Being in jail is a constant negotiation to not get fucked, and I’m not joking about this. In the beginning, everything revolves around it,” he says.

That same night, despite the nerves, he was so tired he was able to fall asleep. But not for long. “Suddenly, I feel something weird, and when I opened my eyes, the same guy from the shower was resting his penis on my hand. I jumped and the guy laughed again and said that it was a game,” Imagine José Rafael Guzmán, the comedian, saying this with a straight face. But something happened in that moment that he wasn’t expecting. Another one of his cellmates, El Cholo, an old man who came from federal prison, interceded on his behalf.

Coño

For black people, he was white, for white people he was Latino, for Latinos he was Venezuelan and he was the only one. He didn’t belong to any group. “The most important thing is who you ‘walk with’ in jail. Do you understand, Coño?” said El Cholo. “Coño,” which literally means vagina but is used as “fuck” in Venezuela, was the name they gave him when he got to jail. Why? Well, because José Rafael says “coño” every three words.

“I’d like to say I was a man’s man, but no. I knew that the physical way wasn’t gonna be my way, I had to use my head. You have no strength to overpower a man who lifts 180 kilos, who’s working out all day, who’s ripped, and wants to fuck you. I’m really proud of the fact that I didn’t have to fight anyone, not even once, and I got out unfucked.”

The first few days, he suffered some extreme bullying, there was always someone looking for a fight. But José Rafael fought back with comedy. He told stories and sang songs like a human jukebox. “‘What song do you like? Back in Black?’ And then I’d give a concert, imitating every instrument, which was something I did in school, and they’d laugh their asses off.”

Asking someone who’s been in jail if he’s been fucked is an indiscretion.

Eventually, he stopped being Coño and became “Venezuela.” And his peers, who had already grown fond of him and didn’t understand anything about what was going on in his country, from time to time cheered “Venezuela libre!”, which of course had a double meaning for him.

And there he was, mingling with rapists, thieves, narcos, and even murderers. Negotiating every day and making allies. Allies that then became friends. They taught him how to fight and he learned how to speak English. In exchange, José Rafael, who had become this tiny world’s culture minister, not only entertained them but provided moral support.

The prison system breaks you, they take the sun away so you can’t fight, they give you a uniform so you lose your identity. “We had one hour of sunlight per week, and even so, some inmates didn’t even want to look outside and covered the windows with toilet paper.” They told him that daydreaming about what’s outside was harmful, that hope was a disease and he had to focus on the present. They also taught him that in jail you’re not a lesser man if you cry or a better man for fighting.

Something to hold on to

Meanwhile, his friends had assembled a team to help pull him out of jail. In the closest circle he had Valerie Lollett, Oswaldo Graziani, and Silvia. Oswaldo handled the lawyers and Valerie was in charge of managing José Rafael’s anguish. In the second circle, Ximena Otero and Led Varela coordinated resources and helped compile a file good enough to explain to an American who is José Rafael Guzmán: a Venezuelan Seth Rogen with social awareness.

Guzmán in a Texan jail, talking to his people. Photo: Silvia Baquero, 2019.

After a couple of weeks in jail, he was obviously accumulating ideas and he bought a legal pad and a pencil (which he tied to his hand at night, in case any of his neighbors got happy and creative) to get to work. Thinking he’d be out quickly, in the beginning, he limited himself to writing a couple of ideas, but when he realized his case wasn’t making any progress, he ended up writing the entire script for his next stand-up.

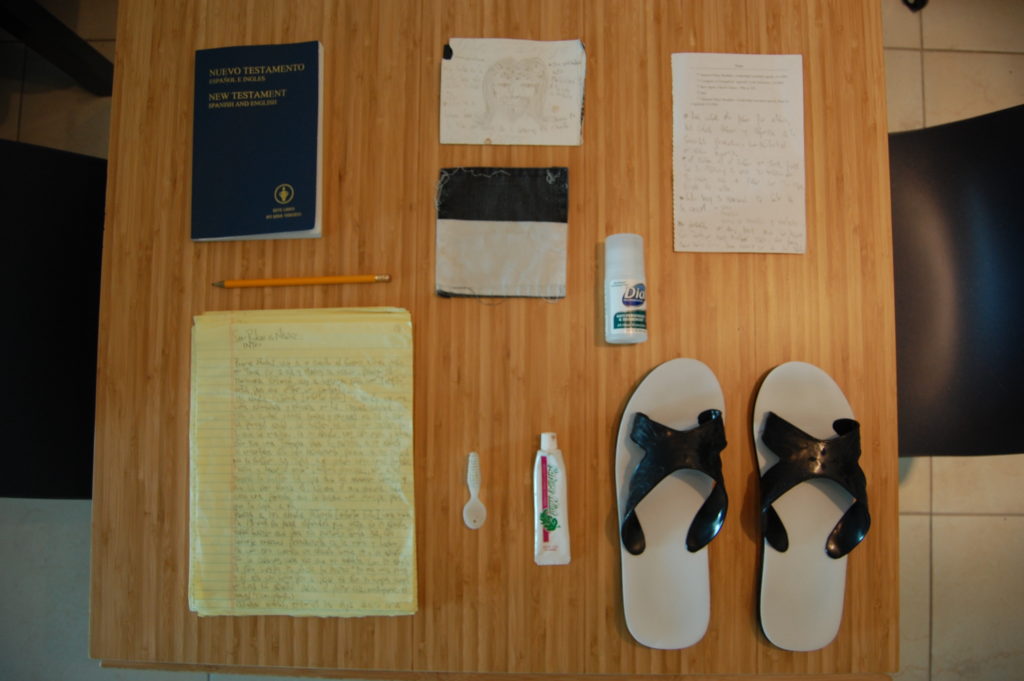

The comedian’s belongings while he’s in jail in Texas. On the left, a legal pad with new ideas and bits for his stand-up. Photo: Raúl Stolk, 2019.

The name was right there: “Sin robar a nadie” (Without Stealing from Anyone). A sort of mantra that he’s been using for a while. José Rafael holds on to certain phrases in an almost compulsive way. “Sin robar a nadie,” “until it’s amazing,” “inspiration: Arnold Schwarzenegger,” and “God, give me peace but don’t take the war”. He usually says the last one every time he’s going on stage and it became a prayer that he repeated every night, in jail, often skipping the second part.

Because José Rafael did pray. “You need something to hold on to.” He read the Bible a couple of times and connected with a Muslim man who prayed five times a day. Sometimes he joined him “praying his own shit.” He was a Jordanian journalist who had traveled to California to treat his wife’s advanced breast cancer. They were hoping to relieve some of the pain with cannabis-based patches. When they crossed the state border to Texas he was taken into custody by Border Patrol and he landed in the same prison as José Rafael.

There’s a lot of confusion in several states after hemp was legalized by the federal government. According to the statute, in order for cannabis to be considered hemp, it should have less than 0,3 % THC. So, states with strict regulations tend to make mistakes between what’s legal and what’s illegal, and to figure it out, they need to run expensive tests that simply aren’t justified when it’s a minor infraction.

José Rafael doesn’t get people who demonize cannabis.

Sin robar a nadie

Eventually, his lawyer and the prosecutor saw eye to eye and both asked the judge to dismiss the charges. And even though this was a big breakthrough, they still had to wait for the judge to review the file and confirm the motion to dismiss. This process took several weeks. During those days José Rafael came very close to giving up and paying bail, no matter the consequences, but Jeep kept him on track: “You’re thinking like an animal now, because you are in a cage and you’re scared and not thinking straight.”

His friends coordinated resources and helped compile a file good enough to explain to an American who is José Rafael Guzmán: a Venezuelan Seth Rogen with social awareness.

Finally, the judge dismissed the charges and granted him freedom. The announcement came as a surprise, but it wasn’t like in the movies: instead of happiness, he was riddled with anguish. The day he was released, October 18th, ICE agents picked him up in jail and took him to one of the initial centers where he had been processed. He didn’t have time to think that the nightmare was over. The new threat was that he was being taken to a holding center for immigrants and then he’d be deported. They played with him, just like Venezuelan cops do. But after several hours, and after José Rafael asked to speak with his lawyers (yes, in plural), they let him go.

They let him go, just like that, in the middle of nowhere. Walk away, leave. And that’s how he made it to the gas station and called Valerie: “Come get me.”

He’s in Miami now. Wearing the same black shoes he was wearing when he went to jail, but with shoelaces. He has tons of plans and he’s completely free, and he’s filing for an extraordinary ability visa. His eyes sparkle when he talks about the ideas for his new show and future documentary projects, but you can tell he’s still shaken.

José Rafael knows that what he went through is not even close to being in jail in Venezuela, but at the same time, jail is jail. “My time in jail is the exact amount of time to say it wasn’t a big deal, but long enough to know how it is on the inside and being terrified by it, especially because I’m just like you, like anyone else. Just a guy who stole from no one.”

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 21 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate