Caught in a Perfect Storm

Disinformation, a complex humanitarian emergency, and a government with no credibility: this is the context when COVID-19 reaches Venezuela.

Photo: Ivan Reyes.

“We’re ready, we’ll get through this.”

Out of everything Nicolás Maduro said on Thursday, March 12th, during his national address, that’s the phrase that lingered the most, raising questions on the presence of coronavirus in Venezuela. A few hours later, Vice-President Delcy Rodríguez spoke of two patients who tested positive for COVID-19. No one dares to talk about the cases we don’t know of.

In the last 72 hours, the pandemic (declared as such by the WHO, on March 11th) was discussed in hush-hush on the street. There’s a suspicious case in the Vargas Hospital, and another in the Clínico Universitario—where there’s no running water. There’s another case in El Algodonal (a national reference hospital for respiratory diseases), a woman who almost turned in DOA. There are over 30 suspicious cases, Maduro said.

The population in Caracas wasn’t surprised. This is the capital of a country submerged in a complex humanitarian crisis, where over 80% of its 306 public hospitals have no supplies, medical equipment or staff, according to the most recent data provided by NGO Médicos Unidos por Venezuela.

“There’s a suspicious case in the Vargas Hospital, and another in the Clínico Universitario—where there’s no running water.” Photo: Ivan Reyes.

By the end of January 2020, when numbers were already exploding in China, expert epidemiologists stated that, with no direct flights China-Venezuela, the odds of the disease reaching us were very slim. And while the number of affected people was on the rise and the virus reached Colombia and Brazil, the streets in Caracas looked the other way. “It won’t come here, because it can’t survive in warm weather,” a woman said while waiting in line for the bus.

“We’re set for a perfect storm of huge health problems,” Dr. José Félix Oletta, a former Health Minister, said a couple of days ago. In public hospitals, 35% of ICUs don’t work; in 46.6% the X-ray units are busted; in 94.2% the MRI and tomography equipment are broken, and in 51% there are no supplies like gloves, facemasks, soap, security goggles or disposable scrubs.

In 43.2% the water service is faulty, and in 31.8% there’s no running water at all. To top it all off, power generators don’t work properly in 31.4% of hospitals, say the surveys by Médicos Unidos de Venezuela.

Most caraqueños already know this and the scene is agonizingly recreated in other cities of the country, where operating rooms are cleaned just with water because there’s no bleach or disinfectant.

Something else that stood out from Maduro’s address is the 45 “sentinel” hospitals; citizens know, from experience, that if you seek attention for pain or fever, you have to bring in the meds yourself.

“Just imagine, we’re all gonna die,” said Rosa Aponte to her husband after hearing about the two confirmed cases. “God have mercy on our souls, you think we’re prepared? If it was already scary to get in the subway!”

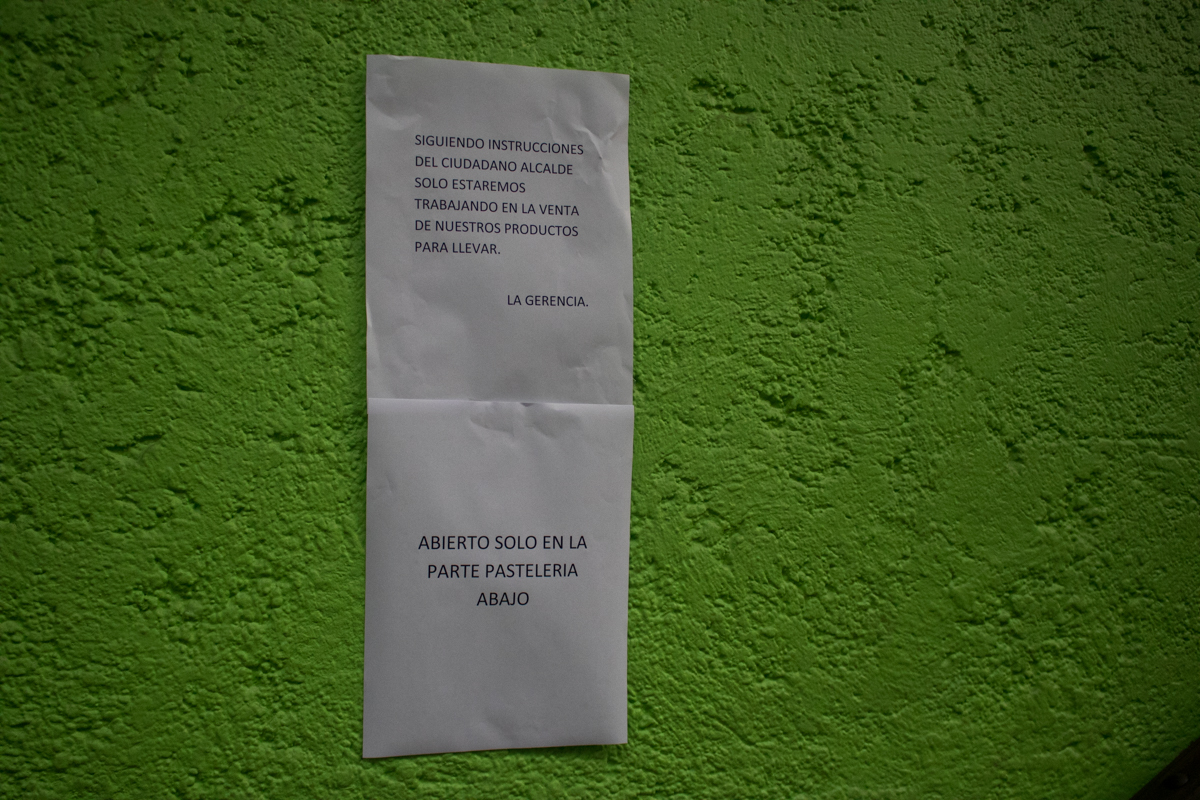

“Following instructions from the mayor, we’re only selling our products on takeaway; Management. Only open through the bakery downstaris.” Photo: Ivan Reyes.

The Caracas Metro, a mass transportation system opened 35 years ago, is a ticking time bomb. Passengers ride with tuberculosis, HIV-AIDS patients beg for money, and it’s always back to back, face to face, belly to belly. “In a train car, there’s no room to breathe and if someone sneezes, it’s game over,” Aponte added.

The WHO says that masks should only be used by those presenting flu symptoms and patients with chronic diseases (besides health staff), but Delcy Rodríguez recommended, in a countrywide broadcast, that everyone should wear masks, without explaining why or their availability. Lines formed at drugstores; masks were $5 at the larger pharmacy chains and, by Friday, with the confirmed cases, there was already a shortage.

The same happened with hand sanitizers and rubbing alcohol. People on the streets go about with rag-covered faces, street hawkers wear their own protection and fare collectors at buses avoid contact with passengers. Mass hysteria was reined in mostly because of how soon all gatherings, forums, workshops, concerts, graduations and classes were suspended.

By the way, there wasn’t enough time for schools to talk about coronavirus. There’s still no plan on how to guarantee the full school year, with Maduro only saying that homework will be sent over the internet, in the country with the slowest and worst connectivity in the region, where urban areas may spend over a year without internet.

Yet that suspension of gatherings from the regime probably explains the silence on the streets, on a payday Friday.

Despite addresses to the nation by two major regime figures, confusion and disinformation is widespread in Caracas. Photo: Ivan Reyes.

Healthcare providers still voice their concerns; Mauro Zambrano, a union leader, demanded gloves and masks for his staff. “They’re afraid to go to hospitals if their safety isn’t guaranteed,” he repeated in a press conference a few minutes after the confirmed cases were announced.

“Washing your hands” is the most publicized advice by regime officials at the moment, reminding citizens of how Caracas (the most privileged Venezuelan city regarding public services) gets an average of 44 hours of water a week, according to NGO Monitor Ciudad.

Flights to and from Europe and Colombia are suspended for a month and, at the time of writing, measures are being studied for the borders. Colombia has already closed its Venezuelan border and Maduro says he’s asking China for experts, completely disregarding the local scientific community.

There’s a lot to clear up in public opinion while the events develop and a national health emergency is declared by a regime that’s always had a problem with using the word “emergency”. Regime figures ask time and time again for a non-politicized approach to the crisis, but use their next breath to demand the end of U.S. sanctions. Citizens, meanwhile, trade rumors on social media and quite a bit of jokes, their only defense against the utter uncertainty of an already stressful future.

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 22 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate