Children Play and Resist in La Cota 905

Through quite an inventive experiment, NGO Caracas Mi Convive discovered how kids perceive their lives at one of the most violent places in Venezuela’s capital.

Photo: Caracas Mi Convive

Often, when la Cota 905 is mentioned in public, the discussion is about armed gangs or the police, a constant conflict for as long as residents can remember. The families caught in the middle are rarely spoken about in the media, and they’re who we talk to the most at Caracas Mi Convive.

In our visits to la Cota, we discovered two very inspiring things about the children that eat lunch every day in the community kitchen run by our sister organization, Alimenta la Solidaridad (a nationwide network of community kitchens for children in impoverished areas). First, they still played, even in this complex and harsh environment. Second, they’re very sensitive to the violence they constantly witness in the neighborhood.

When we enter la Cota to visit the community kitchen, it’s not like other working-class communities in Caracas where we work; their streets are very narrow, and people don’t spend too much time outside. They’re either going to work or coming back, as in a perpetual state of fear.

Yet the kids always welcome us with open arms.

Usually, two or three kids walk us to the community kitchen. Outside, there’s a somewhat wide space with a privileged view of western Caracas, where kids of la Cota have invited us to the “Chuli Baby,” a sort of summer camp activity with catchy phrases that invite a simple dance. This is how it goes: a small group of kids start, we follow, and sooner than you know we have a small crowd around dancing as well. Their families get out of their houses to watch.

Through this bit of joy, these children break fear. This inspired us —following psychoanalytic theory— to explore the way they perceive their community through drawings (an experiment we also did at El Cementerio and 23 de Enero, all low-income areas of western Caracas).

They made colorful presentations of their school, their homes, and their families. Some even with kind messages (like “I love you”) and, at first glance, these drawings weren’t different from the ones any other kid would do—a real expression of resilience in itself. This could mean they see the positive side of a community punished by violence.

The folks of Caracas Mi Convive working with the kids of Cota 905.

Photo: Gabriel Osorio / Caracas Mi Convive

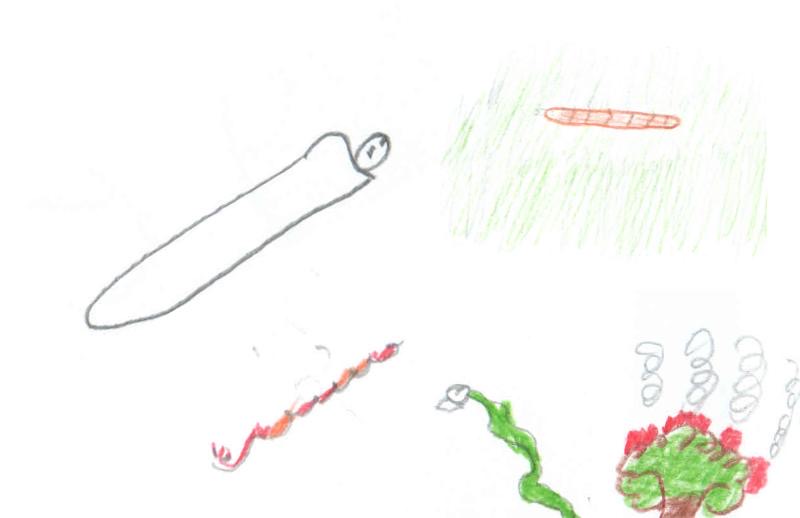

But when we asked them to draw the things they didn’t like about their community, what they came up with was drastically different: they could portray different types of guns with concerning accuracy, distinguishing between handguns and long firearms (such as AR-15 rifles). They also drew grenades, brass knuckles, joints, and the walkie talkies gangsters often display in front of them. They also drew violent events such as killings and shootings between gangs and the police.

One of the most noticeable things many of them drew were snakes. When asked, one of them said: “This is one of the snakes that spit poison, bites, and kills people. I’m very afraid of them.” Other children described similar things, saying that (despite never actually seeing them) the animals lived in their community.

‘This is one of the snakes that spits poison, bites and kills people. I’m very afraid of them.’

In Caracas, when you have a problem with someone, you say you have “a snake” (una culebra) with that person. These “culebras” between young men from poor neighborhoods are known for creating feuds in which someone is killed, the victim’s family must avenge the death, and the family of the newly murdered follows suit. It’s all paid with blood and carried out for generations.

So these kids often hear things like, “a snake killed him,” or “he died because of a snake.” They believe it’s actual feral animals in their barrios, which makes them afraid of the next victims.

Nobody explains to them what’s going on. No one listens to them. Instead, it’s like there’s a veil of secrecy on the subject; before drawing the guns and drugs, a group was unsure about talking about these topics, and some commented that they’d run into trouble if they did.

The active role of infants in their communities is often undermined, in part because we tend to see them as passive individuals unaffected by their surroundings—and it’s terrifying to accept the hard reality they live in. But what the Chuli Baby dance and the first drawings tell us, is that these kids have the potential to overcome the most terrible of circumstances and transform the places where they live.

Inside la Cota 905, there are real children with hopes and zest to explore the world, and we want to open a space in which their voices can be heard. Maybe this is the first step to end these cycles of violence and substitute fear with a true understanding of what these poisonous snakes really mean.

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 22 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate