The Growing Americanization of the Venezuelan National Identity

Many Venezuelans have traditionally admired the U.S., but 2020 brought on something new: a deep identification with American symbols and politics, at home and abroad

A society rediscovering itself.

Photo: Centro Comercial San Ignacio

The last time I was in Caracas was during the 2017 protests. Between the tear gas, the violence, and the chaos that ruled the city during those days, there was one thing that I noticed and stayed with me for a long time: there were old posters along the Prados del Este highway, in middle-class eastern Caracas, advertising a Thanksgiving bazaar from the previous year. This astonished me not just because there were people hosting bazaars during times of food shortages, but because a sector of the Venezuelan society was commemorating a holiday about English pilgrims sharing a meal with North American natives.

What makes the bazaar thing stand out for me now is probably how this happened during a time where fanaticism for Donald Trump wasn’t in vogue yet, seeing people displaying American flags and bald eagles on social media was rare, and Venezuela wasn’t even close to American politics as it is today. These were genuine people who identified with American culture, and celebrated this holiday as if it was a folkloric tradition; all in a country where the only references we have of Thanksgiving are on American TV shows.

From Rockefeller to Trump

This isn’t a new phenomenon. Venezuelans expressed a certain admiration for the American culture for most of the 20th century. We were a nation where the middle class flew to Miami just to shop; we even made an aphorism, ‘ta barato dame dos. We allowed companies like Sears to open stores so they could sell us American goods, people like David Rockefeller introduced the concept of supermarkets to Venezuela, and the most-watched sport in the country was Major League Baseball. We could write an entire book listing many other examples, but the general conclusion is that the influx of American culture into the country was inevitable.

If people like that feel this American already, imagine the entire generation of young Venezuelans who came here at an early age and are being raised under an American identity.

Back then, Venezuelans assimilated parts of that culture in a way that didn’t completely compromise their identity. The discovery and exploitation of oil during the first half of the 20th century caught the attention of many U.S. companies, such as the Creole Petroleum Corporation (now called Exxon), which brought a lot of their American specialists to our soil. That’s how a heavy American presence in Venezuelan society, its culture, its politics, its architecture, and above all its economy, set in. These Americans contributed to modern Venezuelan culture, especially in the prevalence of the automobile over public transport, the introduction of baseball as the national pastime, and even many popular phrases of the Venezuelan jargon.

Caracas was a close ally of Washington during the Cold War and, until Chávez, the relationship was tight. And while Venezuela was covered with American culture, our identity never really changed.

What we encounter today is an entirely different ball game. It’s not your neighbor eating a cachapa while wearing a Red Sox jersey anymore—it’s your childhood friend campaigning for Trump, waving a huge American flag, and defending the right to bear arms as it was originally “intended” by the founding fathers.

It’s widely understood that the utter destruction of the economy and institutions has forced many Venezuelans to flee to the U.S. for refuge. However, what hasn’t been widely documented are the long-term ramifications of this exodus. I could write extensively about my personal experiences in the seven years I’ve lived exiled in the United States, write, for example, about a close friend of mine from Zulia (arguably the proudest and most autochthonous region in Venezuela) who confessed to me that he doesn’t feel anything for his home country anymore, he just simply accepted America as his nation now.

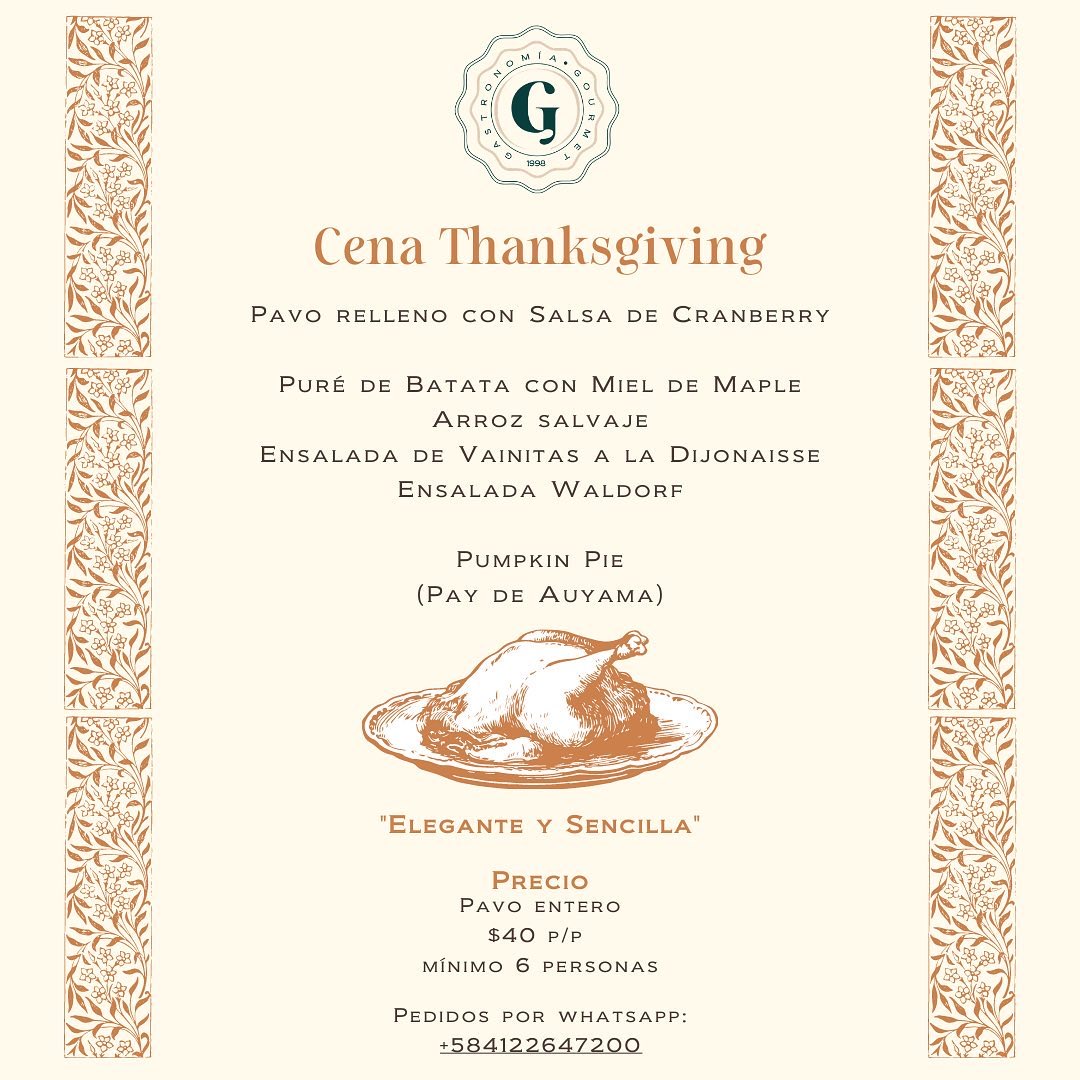

A recent Thanksgiving menu in Venezuela. Notice the dollarized price.

The Landmark of the 2020 Elections

This year’s presidential elections were a clear example of how America has become a kind of second home for our society. We witnessed how Venezuelans participated with tremendous passion in the American political process as if it was their own. Organizations such as Venezolanos con Biden and Venezuelan-American Republican Alliance were the face of both parties’ campaigns to attract the Latino vote. We have figures like Daniel Di Martino being heavily involved in the alt-right movement of the Republican party, and former AN deputy Leopoldo Martínez holding relevant positions in the DNC. Social media was filled with Venezuelans spreading conspiracy theories like QAnon, and with personalities like Debbie D’Souza singing “America the Beautiful” and teaching classes on “socialism” at PragerU; we even had our famous singer Lila Morillo performing a kind of Star-Spangled Banner and Gloria al Bravo Pueblo remix at a Trump victory party.

All of this happened with Venezuelans that have a few years on American soil; if people like that feel this American already, imagine the entire generation of young Venezuelans who came here at an early age and are being raised under an American identity. Kids that, even though they know they’re Venezuelans, speak English as their mother tongue, celebrate the Super Bowl as a holiday, and ignore much about Bolívar and Páez but know about Washington and Jefferson. They’re Americans that just happened to be born in a South American country.

The assimilation of American culture was expected. According to a 2017 study by the Pew Research Center, there are around 421,000 people of Venezuelan origin in the U.S., many of whom are probably planning to stay permanently. What’s shocking is the speed and easiness at which so many Venezuelans identified so strongly with America. Less than a decade ago, nobody would have believed that Thanksgiving or the 4th of July would be part of Venezuelan holidays, yet it’s key to understand that our nationality has been tainted by poverty, corruption, and crime. Many of these people have found refuge in the American identity to feel part of a nation that makes headlines for other reasons than its child mortality rate.

I can’t predict if the process we’re going through will have a positive impact or not. What I can say is that in the next ten years, we’re going to see more Venezuelan Thanksgiving bazaars.

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 22 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate