Heading to the Longest Hyperinflation in History

Venezuela surpassed fifty percent in monthly inflation rates in 2017 and it has gone over that number many times since. But for the last seven months the monthly price increase has been lower. If it continues this way, it could declare itself hyperinflation free in January 2022. Will it do it with elections coming up?

Photo: Reuters

Venezuela could break another record in 2022, and not an Olympic one, but rather an economic one and an infamous one at that: the most prolonged hyperinflation in modern history.

We’ve been in a hyperinflation cycle for 45 months and if we can’t manage to keep the monthly price increase below fifty percent in the upcoming months, we’ll dethrone Nicaragua in 2022.

The current historic champion, the Nicaraguan hyperinflation, went on for 58 months: from June of 1986 until March of 1991, according to research by economists Steve Hanke and Nicholas Krus, published in 2012 with backing from the Cato Institute.

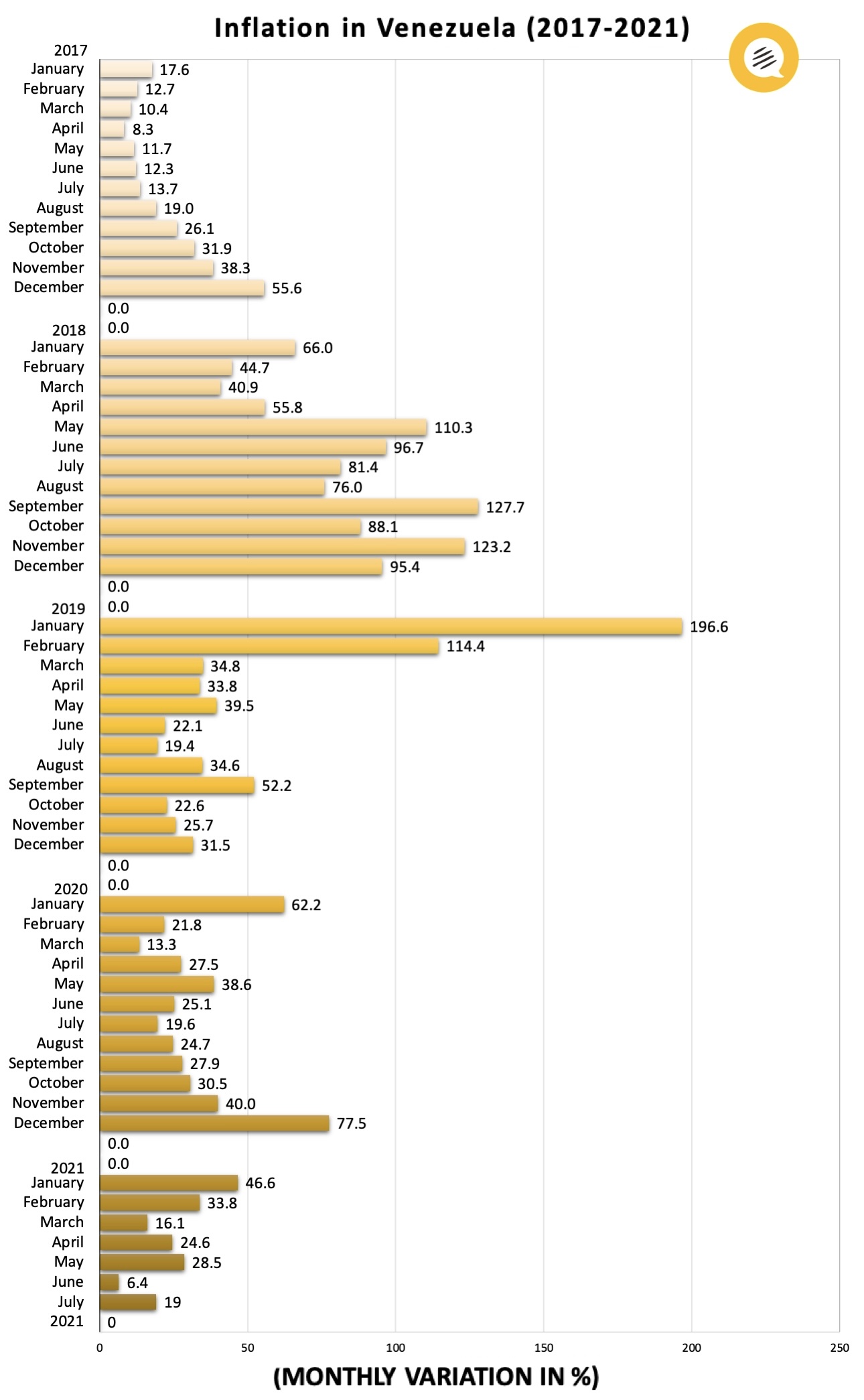

Right now, things aren’t looking too bad. So far in 2021, Venezuela has managed monthly inflation rates below fifty percent, since in the first seven months, the price hike slowed down noticeably: 46% in January, 33% in February, 16% in March, 24% in April, and 28% in May, according to data released to date by the Banco Central de Venezuela (BCV). According to the Observatorio Venezolano de Finanzas (OVF), June registered 6.4%—the lowest rate since 2017 (one digit)—and 19% in July.

These monthly price increase rates are huge if you compare them to any normal economy in the world, but for Venezuelans, they seem small compared to the monthly inflation peaks we’ve had since 2017 when the hyperinflation cycle began in Venezuela: 55.6% in 2017; 127.7% in 2018; 196.8% in 2019, and 77.5% in 2020.

For a country to be considered free of hyper-inflation, according to the thesis by economist Phillip D. Cagan, it must go below fifty percent in monthly inflation rates for twelve consecutive months.

Nicolás Maduro’s regime is trying to stop inflation by keeping the legal reserve requirements which dried the banking system’s liquidity, bringing back into play price controls and trying to favor national production by lowering almost 600 tariff lines.

Experience tells us that the first measure could help, but the second and third would most likely lead to shortages, as a result of low production capabilities by the national industry (located at around 10 and 20%); and an inflationary upturn, because many of the imported goods which were lining the market that was duty-free and free of tax, will now have to pay those fees again.

Furthermore, since prices tend to go up in November and December, because of a higher cash flow during the holiday season, Venezuela runs the risk of ending its streak and having inflation rates of 50% or more.

The same thing happened in 2020: monthly inflation rates ranged between 13 and 40 percent for ten straight months last year, but in December it went up to 77.5%, according to the BCV.

You also have to take into account that, because of the electoral stage expected for November, it’s very likely that the government will increase the number of bonuses and benefits in order to win votes and it’s also foreseeable a minimum wage increase for the fourth quarter of the year. This additional infusion of money, in a system where the offer is limited, usually leads to high price increases in the market.

Public Services Went Up 2,000 Percent

Nicolás Maduro’s administration will go down in history not only as the one where the GDP was reduced by 80% (the Gross Domestic Product is the main macroeconomic indicator used to measure the evolution, productivity, and health of any economy), but also as the period during which Venezuela suffered the world’s highest inflation rates for almost an entire decade.

Since 2017, the average annual inflation rate of advanced economies hasn’t gone above 2%, and in emerging or developing economies it’s 6%. In 2018, according to official data released by the chavista administration, Venezuelan inflation was 130,060%; in 2019 it was 9,585.5%; and in 2020 it was 2,959.8%.

These numbers are lower than the ones registered by international and national independent bodies, but they still recognize there’s hyperinflation since 2017. The Instituto de Investigaciones Económicas y Sociales de la Universidad Católica Andrés Bello (IIES UCAB) estimates that Venezuelan inflation will close at 1,667% in 2021.

Only this past year, public services in the country have raised their fees in over 2,000%, says economist Sary Levy, member of the Centro de Divulgación del Conocimiento Económico para la Libertad (CEDICE).

This interactive chart by CEDICE shows the evolution of prices Venezuela has had in the last 12 months, in each area.

In any case, a four-digit yearly inflation rate still means a huge price increase, not comparable to that of developed countries or emerging markets, the result of the infusion of money to their economies to overcome the standstill caused by the 2020 pandemic.

A Diseased Economy

A price increase that’s as steep and prolonged as the one Venezuela goes through is a symptom of a diseased economic system, much like a fever in human beings. While the structural errors which maintain this economy in shambles aren’t corrected, it’s impossible to get out of this situation.

The national currency loses 99% of its value in shorter periods each time. This is the reason for the de facto dollarization in the past few years. Not only are commercial transactions carried out in dollars, but people are also saving in foreign currency.

None of the economic or financial public policies by chavismo or madurismo have managed to solve one of the main problems for the Venezuelan wage earners: no one is able to live in a decent and integral way from their work, without having to depend on handouts by the State. Currently, there are Venezuelans earning less than ten dollars per month, a similar income to the one by over 3.5 million pensioners and retirees in the country. No one is able to provide for a family with that, since the basic needs in Venezuela already surpass $300.

“Dollarization in Venezuela isn’t the result of an economic policy, it’s the inevitable result of an incessant high inflation rate which has nullified all meaning to the local currency,” IIES UCAB says. The bolivar is still in danger of extinction.

The Big Question

“The interannual inflation tendency in Venezuela sits at 2,000%. It has slowed down, yes, but it is still high, very high. So we have price increase rates which are just as harmful as the ones we’ve had in the previous years,” says Henkel García, director of consulting firm Econométrica.

The price of most of the goods and services is already published in dollars as well as bolivars. Therefore, when the exchange rate changes, the price in bolivars changes automatically. But what contains the black market dollar exchange? García answers:

“For me, it’s the higher offer of dollars to the banking system which also increases the number of available dollars in the entire system, in all the economy. This helped contain the black market exchange rate in June, for example, and the big question is if this is sustainable or not. Do they really have enough foreign currency to maintain the number of dollars offered today in the upcoming months?”

Stopping the Dollar and Inflation by Extending Recession

In June of 2021, “for the first time in years, inflation was only one digit. But there’s a prolonged recessive effect, there’s no credit except for a few companies which can receive indexed loans or in foreign currency. Besides, a progressive reduction of public expenditure in real terms is applied,” warned economist Tamara Herrera, director of Síntesis Financiera, interviewed by Runrunes.

According to estimates by Síntesis Financiera, the purchasing power of the dollar in Venezuela dropped eight percent in the first semester of this year. Herrera said the impact on inflation will largely depend on what the Banco Central does the rest of the year, in terms of dollar availability in the exchange market or the monthly growth speed of the monetary base, for example.

And it’s this same institution that has contributed to the announcement of three monetary revaluations in the last 13 years, which in total have removed 14 zeroes to the national currency to mask its loss of value, and the eight straight years of economic recession in Venezuela.

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 22 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate