Luring Birdwatchers to Venezuela

Photo: David Ascanio

It’s the number one trend in global ecotourism: birdwatching. It’s the activity that raises more money and causes the least environmental damage. And Venezuela was, for a very long time, the South American country with the most birdwatchers.

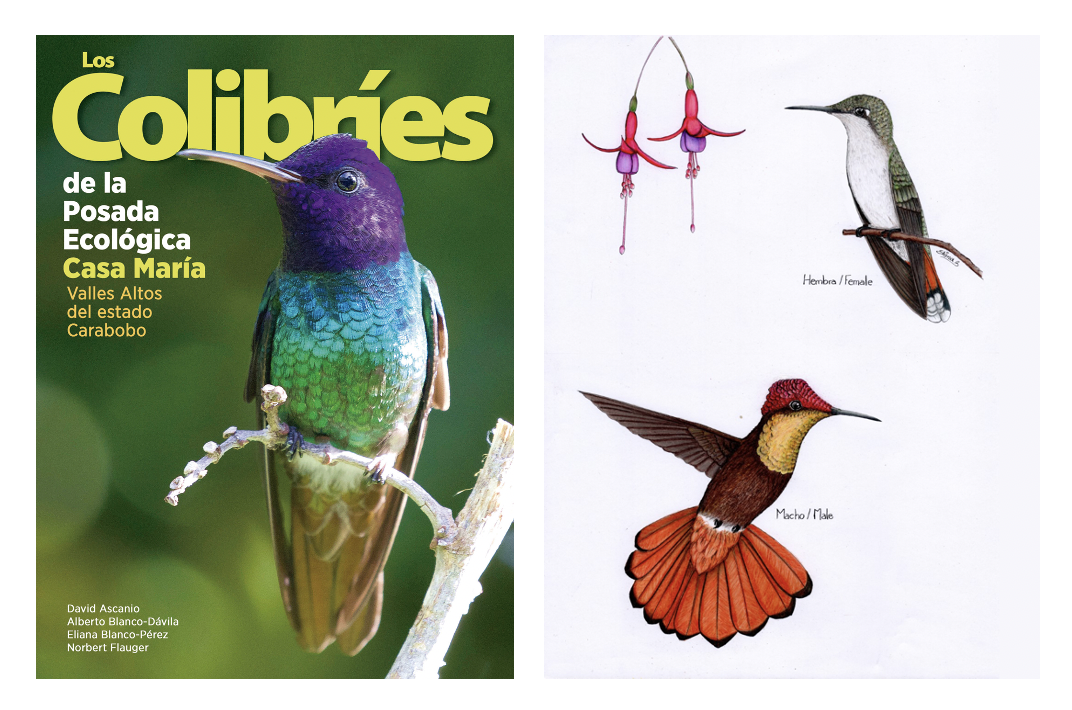

Now that Venezuela has very little option but leaving behind the good old oil rent-seeking, bringing birdwatchers and their dollars back to our country makes more sense than ever. This is why having this team of naturalists working together is great news: David Ascanio, a birdwatching guide for Victor Emanuel Nature Tours; Eliana Blanco Pérez, biologist, ornithologist, and illustrator for the Instituto Venezolano de Investigaciones Científicas (Venezuelan Institute for Scientific Research); Alberto Blanco Dávila, naturalist and founder of the Río Verde and Explora magazines; and Norbert Flauger, owner of Posada Ecológica Casa María.

Eco inn Casa María, located in the mountains of Southern Carabobo, is a sort of laboratory where they’ve been reporting the presence of different hummingbird species in the central stretch of the coastal mountain range. The result of these talents working together was an illustrated handbook titled “Los colibríes de la posada ecológica Casa María” where they mapped and explained some of the biological processes of over thirty hummingbird species that inhabit these ecosystems, and represent around 35 percent of the total species in all of Venezuela.

In the central part of the Cordillera de la Costa, there are plenty of natural theoretically protected areas: national parks such as the Henri Pittier, Macarao, the Ávila, and San Esteban, or natural monuments like the Pico Codazzi and the Alfredo Jahn Cave, among others. But none are managed with the level of environmental responsibility with which Posada Ecológica Casa María is handled. There, German engineer Norbert Flauger began a conservation project which still prevails after twenty years. In the last two decades, Norbert has acquired a large amount of land that had been modified from its natural geographical conditions to be turned into grazing and single harvest fields; he has reforested hundreds of hectares of disturbed ecosystems and was able to restore the cloud forest.

“Norbert Flauger is a conservation hero in Venezuela,” says Alberto Blanco.

He has reforested woodlands that had been completely cleared to substitute them for citrus plantations. Although these reforested lands aren’t primary and pristine forests anymore, but secondary and intervened, they are an invaluable help, since forests retain carbon dioxide, which is the main gas from the greenhouse effect that causes global warming, not to mention hosting great biodiversity.

But Flauger not only declared war on climate change, but also on the extinction of some animal species. The consolidation of his project has made it possible to save threatened species like the helmeted curassow (Pauxi pauxi), the Rancho Grande leaf frog (Agalychnis medinae), thought to be extinct, the puma (Puma concolor) or the jaguar (Panthera onca). Besides, he’s turning this ecosystem into a potentially attractive space for other endangered species, whose presence is limited to a small amount of hectares in Venezuela, such as the Rancho Grande Harlequin frog (Atelopus cruciger) and the margay (Leopardus wiedii).

When forests are fragmented within a territory, habitat degrades and the ecological corridors are cut off, fauna gets trapped in “islands” inside the forest, so it won’t be just a few species becoming endangered, but all of them. Therefore, the conservation work that Flauger is doing in the high valleys of Carabobo is of great importance in a country with no environmental conscience.

The Hummingbird Guide

The Casa María book started with the invitation to Explora magazine’s team to gather experts on certain species of wild fauna in order to build illustrated guides of scientific and educational content on biodiversity in the high valleys of Carabobo. The first two were published in 2019 and 2020, delving into amphibians and snakes present in Casa María and its surrounding area. Last September, the 2021 handbook was launched, titled Los colibríes de la Posada Ecológica Casa María. This document reviews the 35 hummingbird species that inhabit the high valleys of Carabobo.

Written, illustrated, and edited by Flauger and Blanco Dávila along with Eliana Blanco Pérez and David Ascanio, the book explains the nature and importance of hummingbirds for the continent. It showcases all 35 species found in the area, along with fact sheets and illustrations for each of them, and it ends with instructions on how to build and maintain drinking fountains for hummingbirds (with the correct nectar preparation to attract them).

Just like Casa del Ángel del Sol in Mérida, Posada Ecológica Casa María has helped improve life conditions for several hummingbird species who live in the Venezuelan Coastal Range.

Pascual Soriano and Michele Ataroff were successful with the most emblematic specimen in Mérida’s cloud forest, the Mérida sun angel (Heliangelus spencei); Norbert Flauger has done the same in Carabobo with several other species, such as the stripe-throated hermit (Phaethornis striigularis ignobilis), the spangled coquette (Lophornis stictolophus) or the green-tailed emerald (Chlorostilbon alice), the latter being indigenous to Venezuela.

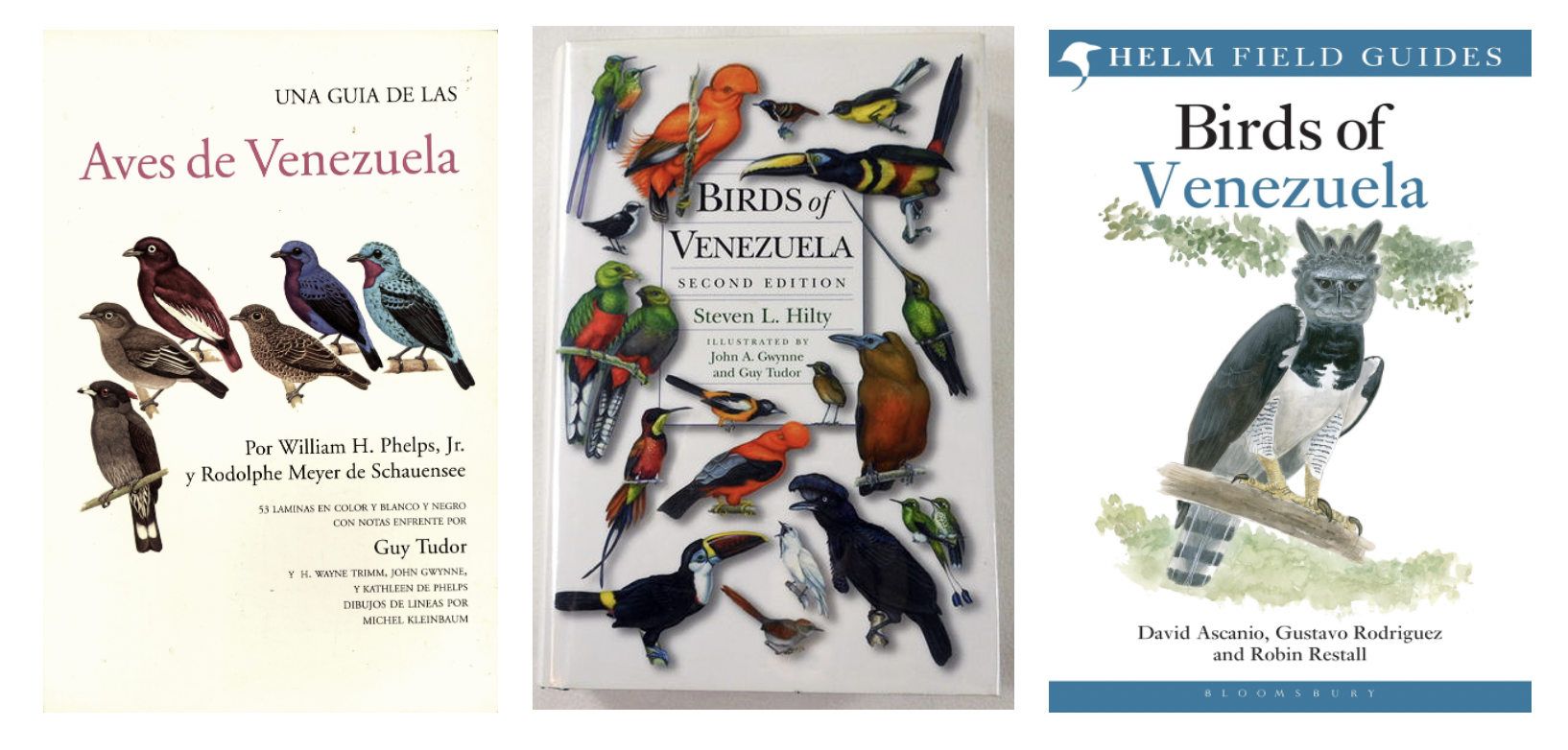

The Casa María hummingbird guide is yet another project that adds to the list of important publications produced in Venezuela since the ‘70s, started by William Phelps Jr. with the guide Birds of Venezuela (1979) in both English and Spanish editions, an utterly important piece for ornithologists and birdwatchers in Venezuela. This guide would inspire U.S. ornithologist Steven Hilty to publish his own Venezuelan birds guide, also titled Birds of Venezuela (2003), both as a tribute and an update to Phelps’s guide.

William and Kathy Phelps’s ornithology and birdwatching legacy is unprecedented in Venezuela; it’s one of those cases where a foreign family sets roots in a land different from their place of origin. Jardines Ecológicos de Topotepuy, founded by Kathy Phelps in southeastern Caracas, is a strong reminder of that legacy; and Alberto Blanco is their scientific projects coordinator. But Venezuela’s avian diversity was also one of the reasons for Mary Lou Goodwin settling in, who came to the country from Portland, Oregon, in the 1940s and is, along the Phelps family, one of the birdwatching pioneers in Venezuela. Her guide Birding in Venezuela (1990)—with five editions, the latest in 2003—is one of the primary works used by professionals like David Ascanio, one of the leading birdwatchers in South America who recently published his own book, alongside ornithologist Gustavo Rodríguez and illustrator Robien Restall: Birds of Venezuela (2017), one of the most complete works on the subject in recent years.

For Alberto Blanco, the socio-historic situation which Venezuela is going through hasn’t clipped his willingness to work in favor of science and ecology. “Mary Lou Goodwin was my boss at the Sociedad Conservacionista Audubon de Venezuela, she’s the one who got me into birds and I traveled all across the country with her. She’s the one who started birdwatching as an organized ecotourism activity in Venezuela. She brought in birdwatchers from all over the world. But I also have to mention Miguel Lentino and Alejandro Luy, from the Tierra Viva Foundation, who have worked non-stop to keep birdwatching alive in the country.”

Green Tourism Instead of Black Gold

There’s been a years-long debate in Venezuela that began with Alberto Adriani, Arturo Uslar Pietri, and Rómulo Betancourt’s positions on the use of oil in favor of the country’s development. Today that debate is pointless, since the environmental urges that the planet is going through are requiring alternative and non-polluting energy sources. Venezuela has to face this reality and join the new paradigm. Waiting for chavismo to step back on its ecocidal policies is naïve, so the population must retake environmental sustainability pathways when the time comes to diversify its economy. Birdwatching is a feasible option, given our history of bibliography and research and a mega-diverse present, since many birds fly the Venezuelan skies, the likes of very few places on the planet.

The high valleys of Carabobo not only have landscaping reserves for the promotion of ecotourism, but also human potential needed to make birdwatching into one of its engines. The best example of this is the network of inns that has consolidated in the area.

There are spaces in Mérida, even within the city, turned into permanent watering holes for migrating birds—like the artificial lagoons from the Universidad de Los Andes’s Botanical Gardens. Los Roques, Margarita, or Paraguaná, as a northerly window in Venezuela, have to overcome the desolate image they carry today, as the result of the destruction of the mangroves, excessive cutting of trees, and the construction of drug trafficking airports. One alternative is to attract tourists willing to pay to watch the skies filled with flamingos and parrots. The large ranches in the plains, for their part, have to redirect their attraction towards concerts by the double-striped thick-knees, horned screamers, and limpkins, in their marshes and moriche groves.

All this requires a chain of logistic elements which not only depend on the presence of birds in their ecosystems, but also on transportation, lodging, and the availability of expert guides who can turn birdwatching into one of the new engines of the Venezuelan economy. Los colibríes de la Posada Ecológica Casa María is one of the steps that need to be taken: it all starts by spreading knowledge about what we have.

This piece was originally published in Spanish at Cinco8

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 22 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate