The Battle for Barrancas del Orinoco

This town located at a strategic point of the Orinoco Delta is being disputed by gangs, guerrillas and security forces. The fighting has left several dead and many questions

“Things are still pretty intense here. Barrancas is still taken. We have counted four dead,” texted Javier (his real name, as with other people’s in this story, is kept private for safety reasons) on the night of January 13th. Twelve days earlier, on January 1st, the town of Barrancas del Orinoco, on the southern border of Monagas and the northern shore of the Orinoco River, was under gunfire.

Some rumors of violence had started to spread on the night of December 31st, when the Doña Carmen liquor store, by order of Fundación Hermanos Álvarez (better known as El Sindicato de Barrancas gang), installed a mountain of speakers in the storefront to make the whole town listen to a New Year’s Eve party. Everybody would have to hear the loud music resounding over the flat, hot landscape. Firecrackers, however, were prohibited by the gang: its members needed to know for certain if something exploding or banging was gunfire or not.

By 3:00 a.m., indeed, something that was clearly not firecrackers broke the party.

A group of masked men in black camouflage fatigues jumped off several boats from the river shore. They carried the red and black sign of the ELN (the almost six-decade-old Colombian guerrilla Ejército de Liberación Nacional) and descended upon the town firing assault rifles and throwing grenades. While El Sindicato barricaded the streets that led to its hideouts and armories, ELN men surrounded the town with checkpoints on every possible escape route.

By noon, for lack of stamina or ammo, the shooting stopped. Javier and his family could finally lift their heads off the ground. Five members of El Sindicato were dead. Two other bodies of guys nobody knew had been left at the cemetery and at the local fish store. All seven were quickly buried, while a large group of wounded people filled the precarious local hospital—but several doctors and nurses fled, fearing the combat would spread to the site. To this date, more people are missing or in hiding.

On January 1st, the National Guard—which is in charge of protecting the river shores—arrived in Barrancas after 4:00 p.m. with CICPC officers and state police—theoretically to restore order. Two days later, armored cars with CONAS and DGCIM men arrived on site. “Those first days,” Javier says, “the officers entered houses to steal food, mattresses, electronics, just to intimidate us.” No one could be out after 8:00 p.m.

Barrancas was under further gunfire on January 4th. By 5:00 p.m., the count added two more dead, and on January 5th, El Sindicato fought briefly with soldiers and police officers on Betancourt Ave., leaving a.k.a “El Pollito” dead.

Not Any Village

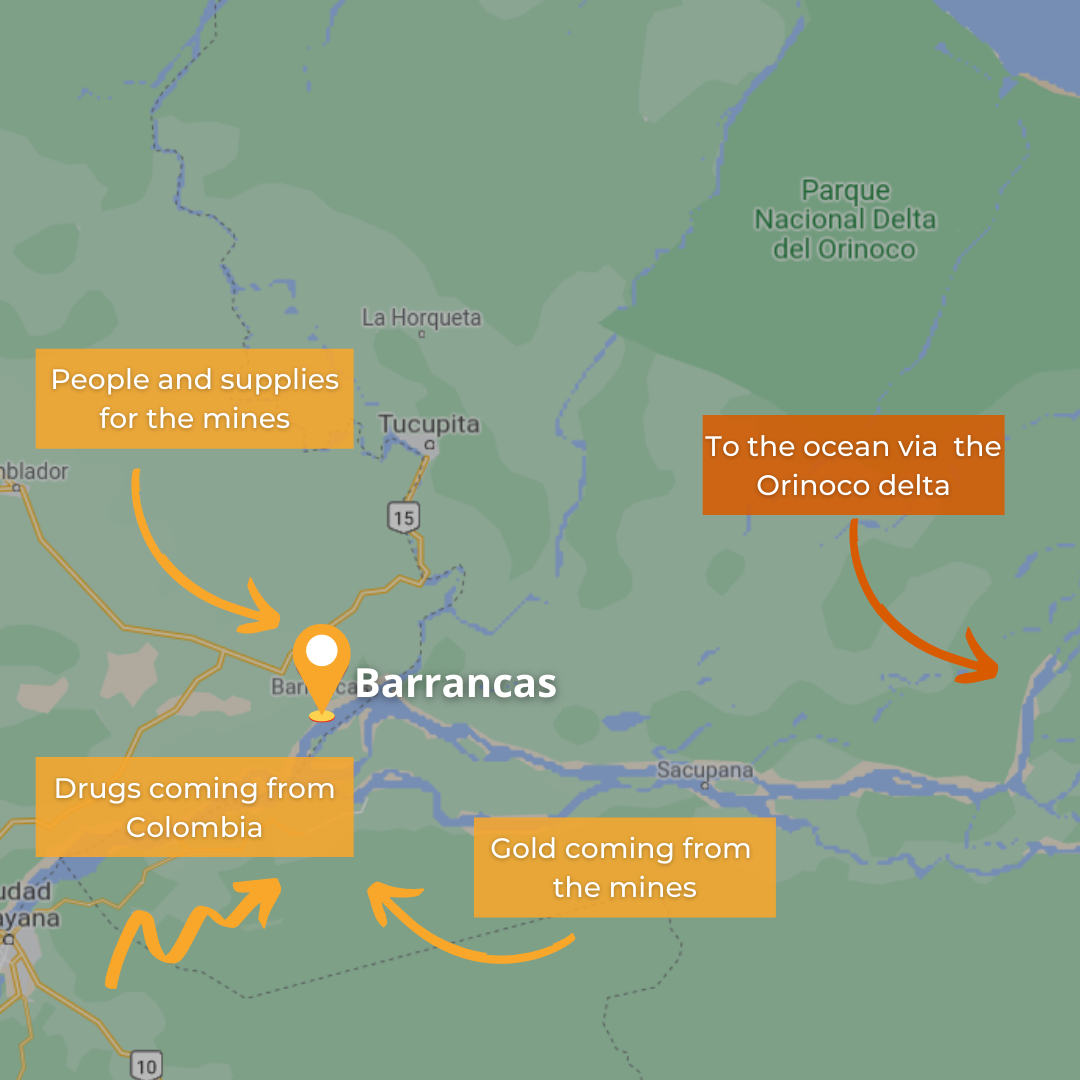

Barrancas is an old town with around 30,000 inhabitants, and it’s become strategic for the illegal economies of southern Venezuela, since it’s located right where the Orinoco River divides into the labyrinth of waterways that is the Delta. Barrancas is also an important station for gas smugglers headed to the mines, sourced by roads and serving fuel to miner boats on the river shore. Those who control Barrancas del Orinoco, control a hub for people and supplies going to or coming from the gold mines in Bolívar, and a checkpoint on the Orinoco just before the narrow waterways of the Delta can lead drug cargo to the Atlantic Ocean.

From Barrancas, according to Javier, you can reach Guyana on a motorboat, an exit route for drugs. It’s a difficult region to watch and protect, very popular among the guerillas and gangs who export drugs to Africa, Europe, and the Mexican cartels. “There’s a lot of drug trafficking here,” says Luisa, another villager. “We don’t talk about it, but everyone knows it. Before the fighting in January, we used to sit on the shore to watch the vessels pass, and the National Guard or the FAES would come and order us to leave. Then we knew that something bad was being transported.”

As usual, everything related to the history of El Sindicato and the illegal economy of the region is made of legends, some of them spread by the armed groups themselves, all of them whispered with fear.

The business of gasoline and drugs in Barrancas was controlled by the “El Piojo” gang, until it was exterminated by El Sindicato in December 2016. They say the battle lasted two days and that even the wives and children of the defeated were massacred and dismembered.

Some say El Sindicato was formed by former oil industry contractors. Others say the gang was the armed branch of a union linked to the mines. According to Javier, the government tried to exterminate El Sindicato in 2020, but it failed and ended recruiting them to protect the drug business. According to another neighbor, Luisa, “those boys of Fundación Hermanos Álvarez have defended us from robbers, men who rape Indigenous women, drug traffickers who force the fishermen to be their mules… the authorities would do nothing. They cleaned the town. We were living just fine. We went to El Sindicato when someone stole our cattle. True, they asked for some money to feed their men. Now they want to topple them to control the river.”

ELN wants to control the river now. Journalist Sebastiana Barráez, an expert in security matters in Táchira, saw in Barrancas the same pattern of territorial occupation by the ELN, which has a strong presence in the mines and now needs to occupy the strategic post of Barrancas del Orinoco. But Javier thinks the newcomers aren’t guerrilla, but another gang competing against El Sindicato. “Those guys get weapons and kill each other. No one is safe here.” People say that a lot of land in the region has been bought by high-ranking officers linked to drug trafficking. Who can ever say who’s who in that region riddled by all kinds of criminal enterprises?

“Nobody knows what’s really happening here,” says Luisa, “and what will happen to us, the villagers, but what I want is the authorities to hunt down the guerrillas, not those boys in the Fundación who care for us.”

By January 18th, Barrancas del Orinoco was still occupied by security forces. At the time of writing, no more fighting has taken place.

Subscribe to our Political Risk Report.

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 22 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate