Venezuelan Migrant Wave Makes Landfall in Uruguay

The Venezuelan presence in this country grows dramatically, as a another sign of a new pattern: the second migration of those who didn’t find a true home in the Andes

Maldonado, Uruguay

Photo: Wikipedia Commons

Venezuelan migration headed to Uruguay has increased by 31% from November 2021 to May 2022. According to the International Organization for Migration (IOM), this represents the highest percentage growth in the region. There are signs that it could be Latin America’s highest increase, in relation to its population

In this country of three and a half million people, the Venezuelan community isn’t as large as in neighboring Argentina and Brazil. In May 2022, the Dirección Nacional de Migraciones (National Immigration Office) confirmed that a total of 20,400 Venezuelan citizens were legal residents in Uruguayan soil; 4,900 more than the previous semester. And those numbers don’t include those who are applying for asylum.

Why is this happening in a country that hasn’t been the preferred destination of the Venezuelan diaspora, like Colombia, Peru, Ecuador, or Chile?

Re-Emigration

The Venezuelan diaspora in Latin America, especially in South America, is mostly made up of conventional international migration cases: people who change countries in search of survival and trying to find opportunities that seem impossible in their homeland. In other words, people who are forced to migrate mostly because of economic circumstances.

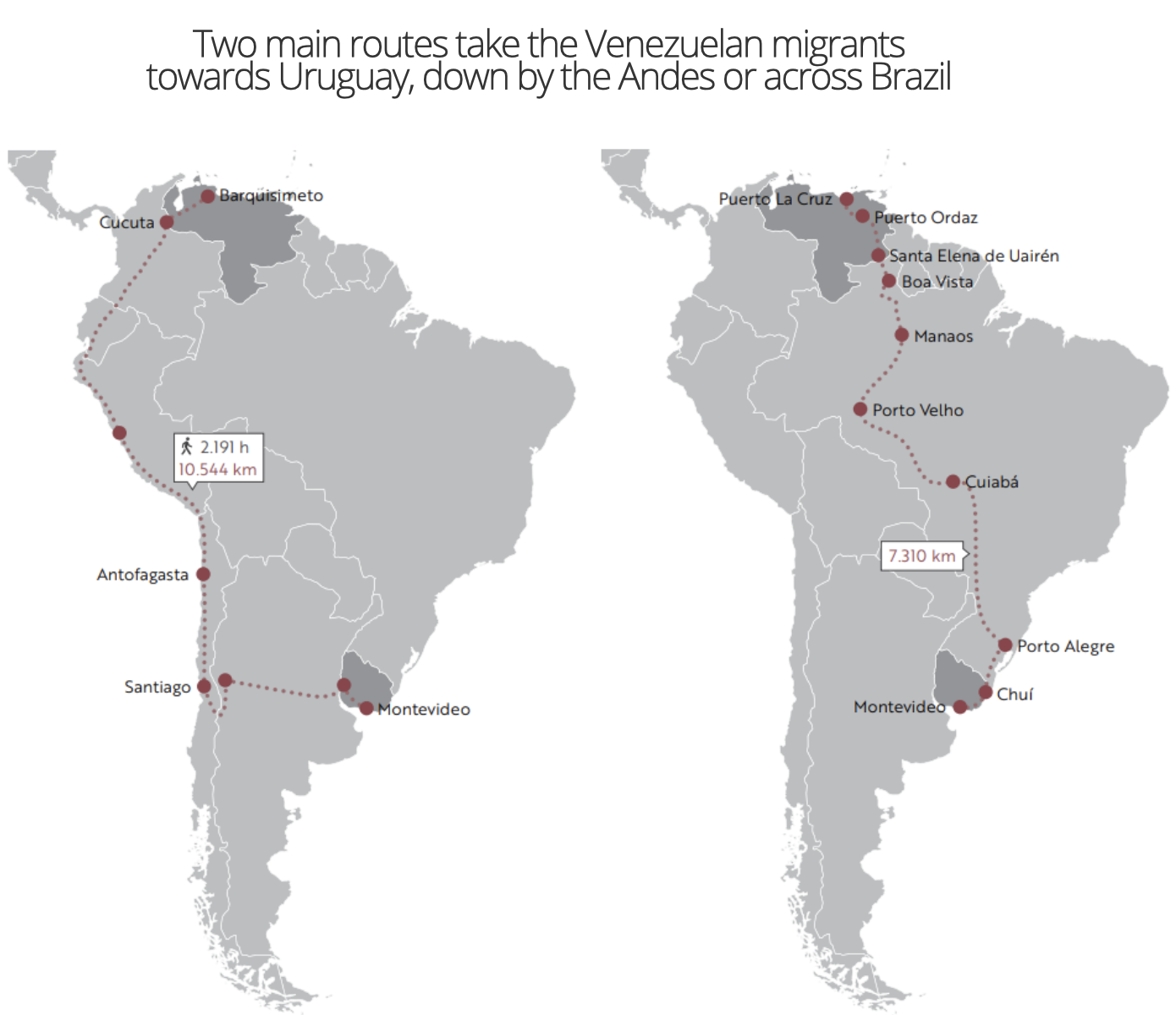

But the context of intense socio-political conflict and economic and humanitarian crisis adds two special singularities to the Venezuelan case. First, the migration volume, which in the last five years has surpassed five million people in the region, according to the Plataforma de Coordinación Interagencial para Refugiados y Migrantes de Venezuela (Interagency Coordination Platform for Venezuelan Refugees and Migrants). Second, the creation of transit routes that began with the caminantes headed to Colombia, that today extend not only to the Andean countries passageway and, more recently headed north too, but they also go through Brazil to connect with the Southern Cone.

This last detail is relevant to understanding Venezuelan migration towards Uruguay, the smallest country in territory and population in the sub-region, which has received Venezuelan migrants that, at first, used to be young and with university degrees since 2015. Either way, Uruguay has also received Cuban, Dominican, and migrants of other nationalities in the same period.

Venezuelan Migration Paths in South America to Uruguay

“Venezolanos en Uruguay”. Ángel Arellano. (2019)

Photo: From the book "Venezuelans in Uruguay", written by Ángel Arellano (2019)

In February 2021, according to the International Organization for Migration, 14,926 Venezuelans had taken up residence in Uruguay: 25 percent with a technical specialist degree and 42 percent with a university degree; 79 percent worked in the formal sector, 17 percent did so in the informal sector, and 19 percent worked independently. This profile has gradually diversified, with families reuniting and a higher number of refugees and asylum seekers.

The closing of borders because of the pandemic starting in March 2020 resulted in an important decrease of Venezuelan migrants into the country. But people kept coming, through border pathways from Argentina and Brazil, looking for shelter or asylum in Uruguay. According to a report by NGO Manos Veneguayas, which gives support and organizes the Venezuelan community, the majority of these applicants came from other countries to which they had already migrated: Colombia, Peru, Ecuador, Chile, Argentina, and Brazil.

Why Uruguay?

There are many reasons for their presence in Uruguay. They range from the search for new jobs and financial opportunities to integration problems and xenophobia in other countries in the region. Multiplying stories of rejection and migration failure have generated a rebound effect headed towards Uruguay, which is getting a lot of attention as a receiving country for re-emigration.

Uruguay is among the Mercosur members with better statistics in terms of migrant integration: legalization, labor force access, education, and legal residence. Uruguay is also well positioned in the region when it comes to political and economic stability. The economic growth projections for 2022 are better than they were pre-pandemic; circling 4.5 percent of the GDP. It has also stood out in how well it handled the pandemic and the absence of xenophobic scandals and anti-immigrant protests.

In the frame of Latin America being hit by the economic crisis, covid aftermath, and political tensions, tranquil Uruguay is looking like a good opportunity.

However, it doesn’t mean that it doesn’t have some hurdles to overcome. The rise in migration also brings up some topics to be discussed and actions to be taken. At the start of 2021, we insisted that the rebound effect of this re-emigration, once the borders reopened, would have an effect on numbers. As expected, the 31 percent increase in the last six months confirms it. Even though the topic hasn’t had a relevant slot in the public agenda, we believe it’s necessary to talk about it where decisions are made, so that this migration keeps an organized and regulated dynamic, and not a crisis like has happened in some countries of the region.

Current Picture

After the paralysis brought by the pandemic, Uruguay managed to quickly recover and even open new job opportunities. So, the employment rate reached 56.9 percent in April 2022. Information technology, health, pharmacy, logistics, and engineering industries stand out as the best perspectives. Although those are areas that have taken in foreign human resources, a large portion of the qualified Venezuelan migration doesn’t work in their professional fields, not just because of a lack of employment opportunities, but also because of regulatory limitations. This mostly happens in the public sector, in primary and high school education, for example: although Uruguay has a teacher deficit, foreigners can’t enter the workforce until their legal citizenship has been approved for three years (a procedure which can take around eight years on average).

While there haven’t been protests against migrants or conflicts of that sort in Uruguay, integration, discrimination, and xenophobia issues shouldn’t go under the political radar. When it comes to migrants working in Uruguay, a poll taken by consultant Cifra (2019) revealed that 33 percent of the national population didn’t agree with this. This percentage was 42 percent in a poll taken by Opción Consultores in 2018.

In a project by NGO Manos Veneguayas (June, 2021) with 140 young migrants between the ages of 16 to 29 years old from all nationalities, 60 percent claimed they didn’t have friends and that they knew few people from their age group, and 30 percent stated they didn’t know people their own age. A report by Ceres (December 2020) shows that three out of four people have a positive view of the interaction with Uruguayans. However, 25 percent think differently.

The Challenges to Come

The current picture shows that Venezuelan migration in South America will continue to look at Uruguay as a promising destination. Venezuelan citizens who’ve had problems in terms of socioeconomic insertion in countries saturated by the diaspora like Colombia, Peru, Ecuador, or Chile, will circulate around the neighborhood in search of opportunities.

Therefore, some challenges await regarding Venezuelan migration, which will increase. More people will arrive looking for better jobs and cohabitation conditions, or to reunite with family members who have already established themselves. The country might find a way to trigger a regulatory change to ease integration into the labor force of migrants who have settled in, especially those with a professional profile. Opening access to getting involved in education, work, and social relationships will be a differential strength to prevent discrimination and xenophobia.

In today’s Uruguay, it’s difficult to understand Montevideo and other inland cities without the melting pot of colors, accents, gastronomy, music, and expressions that have left their mark by new waves of migrations.

Venezuelans came in with baseball, rum, arepas, the programmer, the worker, the teacher, the doctor, the salesperson. What was a small phenomenon happening in the capital in 2015, is now spreading all over the territory.

Migrants have been the past, are the present, and will be key in the future of this small, great southern country. Diversity enriches it and makes it a better place.

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 22 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate