Machine Learning From the Revolution

Twitter bots are no longer enough. Fake video anchors and ad targeting are among the many ways an autocracy can take advantage of increasingly powerful AI tools

Venequian Skynet

In February, two strange ads started popping up all over Youtube. Two videos, edited like news shows by a supposed media organization called House of News, showed their respective news anchors, Noah and Darren, talking about how Venezuela’s economy is “not really destroyed.” Noah highlighted crowded beaches during the Carnival holidays and Darren mentioned revenue generated by the Caribbean Baseball Series earlier this year.

The videos went viral on TikTok and were later played in the state-run news agency, Venezolana de Televisión (VTV). The twist? Neither Noah nor Darren are real. They are deep-fake avatars made with artificial intelligence through Synthesia, a platform that allows users to make similar videos with other avatars besides Noah or Darren just by subscribing.

The House of News videos caused some stir on social media. After all, this was seemingly the first reported usage of such artificial intelligence technologies in the country. Of course, it wouldn‘t be the last.

After the uproar, a government-led bot campaign, the banning of the Synthesia account used to create the ads and their removal from Youtube, more avatars started appearing. Just a few weeks later Nicolás Maduro announced in his show “Con Maduro+” the arrival of “Sira,” an AI presenter that has made frequent appearances in the show. Then, the propaganda site Venezuela News presented two new announcers, “Venezia” and “Simón.” All narrating fake news reports conveying the vision of a crisis-free Venezuela.

The usage of artificially-generated news anchors is not new. Similar news presenters have started to appear in Mexico, Perú, China, and even Switzerland. Also, AI is currently being used for political campaigns. The images in this ad from the Republican National Committee, for instance, are made with AI.

The landmark here is that the arrival of these fake anchors shines a light on an important fact: AI is going to change the fight against misinformation.

We need to understand what exactly these technologies are and what we can do to mitigate their impact.

How it works

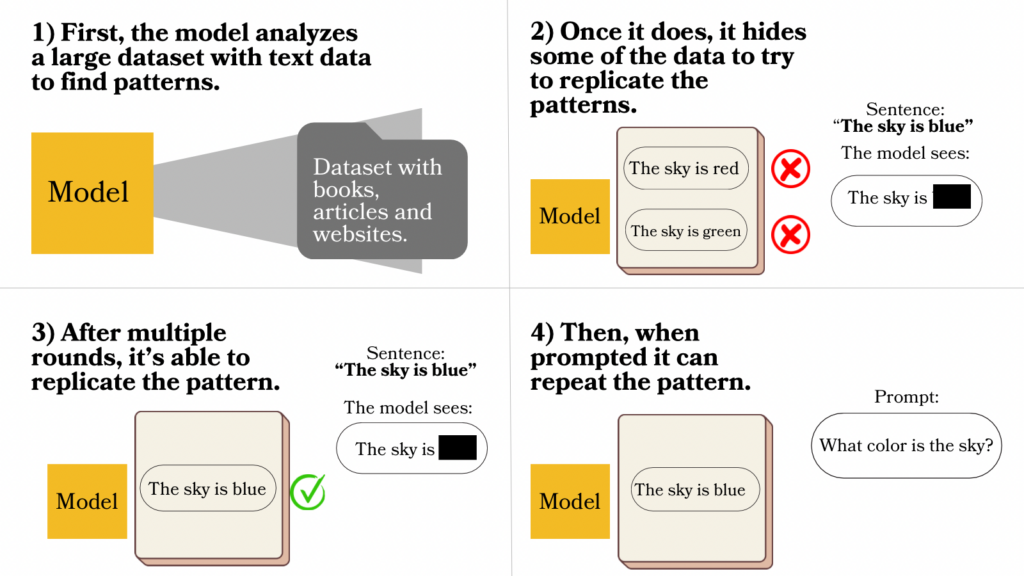

The concern comes from a technology that has existed for a while now, deep learning models: computational systems that are able to explore large datasets and detect patterns. We use them every day, these models are behind social media algorithms or even in virtual assistants such as Siri or Alexa. However, new developments in AI not only detect patterns in data but also replicate them in a surprisingly human-like manner. This is what’s behind software like OpenAI’s ChatGPT or Google’s Bard, which have become increasingly popular over the last few months.

Dr. María Leonor Pacheco is a Visiting Assistant Professor of Computer Science at the University of Colorado Boulder and focuses her research on Natural Language Processing and Machine Learning. She explained to Caracas Chronicles how this technology works: “These are models that learn through multiple rounds of auto-complete.” The AI models are able to find patterns and relationships behind each word in large amounts of text in articles, websites, or books. When presented with a “prompt,” the question you ask AI to activate a search, AI calculates a likely response and generates a coherent text that looks like it was written by a human being.

Sort of like this, but at a massive scale:

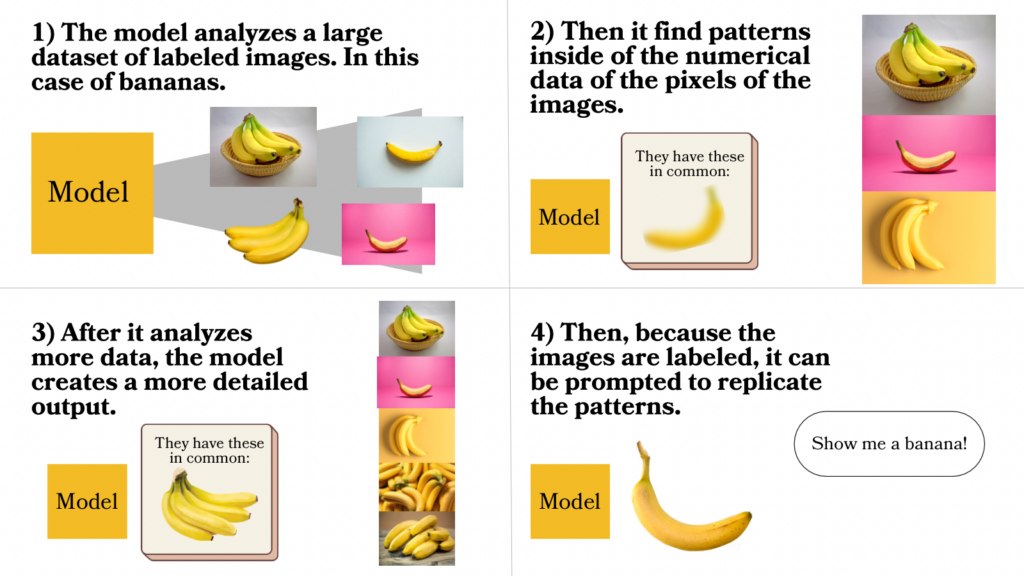

Images can be generated the same way, says Dr. Pacheco: “Each image and pixel can be divided into numerical factors. The model discovers patterns within those numerical factors and replicates them. A cambur, for example, has certain pixel characteristics. The model begins to repeat them and learns to replicate them.”

Sort of like this:

Synthesia uses data from the voice and images of real, human actors. Users of any kind and intentions can also upload their own avatars. Generative Artificial Intelligence models are becoming increasingly accessible to everyone. The reason for this, according to Dr. Pacheco, is that the technology that we all have access to is becoming much more powerful: “The rise is due to the growth in computing capacity and the rise of technologies like neural networks, which in some cases even facilitate parallelization: multiple simultaneous training rounds.” So, with ever increasing computing power in smartphones and personal computers, it’s relatively easy for anyone to enter and sign up to platforms like ChatGPT or Midjourney and create seemingly realistic texts and images, like this one of Caracas in the middle of a snowstorm, and spread fake news like está nevando en Caracas!:

In addition to the creation of fake news anchors, technologies like this are already having an impact in Venezuela’s disinformation landscape. Cazadores de Fake News, a fact-checking organization, already detected cases of AI-generated images being spread around. For example, an image a graphic designer made with AI of a supposed poster of an animated Simón Bolívar movie was taken out of context and it spread like wildfire on social media. Another video, originally made with humorous purposes, that several people on WhatsApp and Twitter believed was true, claimed that “Skynet” was working on a Simón Bolívar android for the Venezuelan army.

According to the director of Cazadores de Fake News, Adrían González, these technologies allow for the creation of mass disinformation content: “Imagine that you want to convince people of a crazy thing like, imports of spaghetti trees in Venezuela are growing. Then, you tell an artificial intelligence ‘create 200,000 different persuasive tweets where they talk positively about the import of spaghetti trees’ and put that output in an online botnet and you set up a campaign that seems very authentic, but it’s totally crazy, totally false”.

It’s so easy! In fact, this is what seven tweets in that premise might look like when we asked the popular Large Language Model, ChatGPT.

“Artificial intelligence can and will be exploited massively in the entire design process of influence operations,” Gónzalez argued, “you can micro-segment your target audience with the use of AI to make a much more efficient campaign, analyzing data about millions of people to know exactly what is the most persuasive message to convince them to vote for a candidate.” AI has been the tool to create specific kinds of automated Twitter, like the ones supporting Alex Saab that had profile photos of non-existing people, made with models like the one behind the popular site thispersondoesnotexist.com.

We need to be ready for this new landscape, and for González, this means going back to basics: “If we do not have tools or training to counteract standard pieces of disinformation, of course, we will fall for artificially-generated ones, which are much more sophisticated. The answer is developing digital media literacy, not only so that people know how to use tools, for example, image reverse search, or to fact-check on Google, but also to prevent other digital threats like phishing”.

One can wonder how many people, across entire populations of all ages and backgrounds, will make the effort and invest their time in developing that media literacy, but either way, we all need to do our part. This is not only getting ready for the changes that are coming to disinformation, but also starting to implement them to create a positive impact. In the same way that they can be used to spread misinformation, they also can share factual reports about the situation happening in the country. That’s what ProBox, a digital observatory that focuses on detecting disinformation campaigns on social media, started doing. They started implementing this with Boti, an artificial intelligence presenter, just like Darren or Venezia. However, instead of disinformation, Boti introduces the presentation of their latest report.

In her video, she says something that is important to keep in mind as we navigate into this new weird era of communication: “Neither technology, nor programs like me are evil, it’s all about who programs us.”

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 22 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate