The Return of Marisol

The largest solo exhibition of the late Venezuelan-American visual artist just opened in Montreal before going to three other museums in the US. With more than 250 pieces, it reframes for today’s sensibilities the vision of a woman ahead of her times

View of the exhibition Marisol: A Retrospective. © Estate of Marisol / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo MMFA, Denis Farley

A creator of the sixties whose approach and proposals remain pertinent. A human being coming from many parts, prone to travel and exploration, who kept a strong connection with Venezuela. A woman who defied traditions, categories and roles imposed by others. Maria Sol Escobar (Paris, 1930 – New York, 2016), better known as Marisol, was many things at once. All of them are fascinating.

Marisol: A Retrospective, which just opened in Montreal’s Musée des Beaux-Arts, MBAM, unveils the entirety of a work much more diverse, complex and far-reaching than the funny, ironic pop art we most associate with her. One can see there how she absorbed influences from Mesoamerican and Precolumbian art – hence the totemic air of some of her sculptures – , but also the late work marked by her diving adventures in Tahiti, the magnificent drawings at the start and the end of her career, and some astonishing pieces like The Generals, where Bolivar and Washington ride a horse made out of a whiskey barrel; the portraits of Desmond Tutu and Georgia O’Keefe; the one depicting John Kennedy Jr saluting her father’s funeral parade; and what may be Marisol’s masterpiece: The Party, rightly displayed as the center of the exhibition.

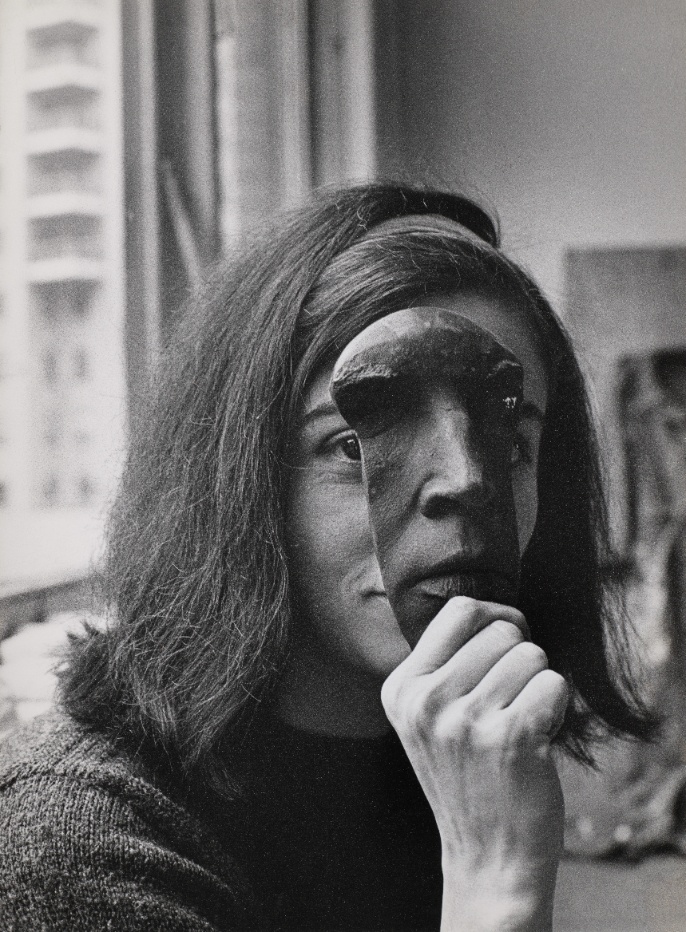

Along with this panorama of her oeuvre, the retrospective opens up the artist’s life. The girl who refused to speak for years after her mother died to suicide when she was eleven. The rising star of pop art that was manufactured by the American media as a “Latin Garbo” whose looks seemed more important than her work. The cosmopolitan creator who fought against the critics that insisted on labelling her art as folk because she had Venezuelan origins. The feminists who attended a conference with a mask and remained in silence to underline the margination of women in the arts scene. The close friend of Andy Warhol or Willem De Kooning who enjoyed parties and vernissages until she was fed up with the frenzy and retired to study and explore another creative stage. The famous woman who refused to marry and have children, and elaborated on her complicated family experience throughout decades of artistic practice.

Under young women’s eyes

Marisol’s work is tattooed in my sensibility. By 1990 I was very into art and I spent entire afternoons perusing among the master works available for all of us at the Sofia Imber Museum for Contemporary Art, MACCSI, in the eastern tip of the magnificent brutalist complex Parque Central. There are many public works by her, such as the Gardel statue in Catia. For me, Marisol was always there. But I know that those who grew up in the 1990s and 2000s could not enjoy Caracas’s cultural offer as I and my contemporaries did. And I had no idea how non-Venezuelans would read her work. Until now.

For a Venezuelan from my generation, it’s very interesting to see what people from this part of the world, younger than me, sees in Marisol. In Montreal, the local press explains in very specific terms why the Museum of Fine Arts, the most important in the city, chose an unknown artist to star in the main exhibition of the year, the one expected to attract more visitors during the grey months of fall and early winter. The journalists say the work is astonishing, good for kids, but especially relevant in terms of what it says about currently hot issues such as gender, the role of women, environment and identity.

© Estate of Marisol / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photo Brenda Bieger, Buffalo AKG Art Museum

The MBAM chief curator, Mary-Dailey Desmarais, a millennial, had to plunge into the oeuvre of an artist she only knew by name, to find that her massive wood sculptures were not only unique in the 1960s, but that Marisol’s subjects resounds with the big struggles and conflicts of today. “We are lucky to be able to put under the spotlight an artist who was forgotten but who deserves all our attention”, said Desmarais to La Presse, “not only because of her work’s aesthetic and innovative quality, but also because of her social and feminist engagement”. That Marisol was a very independent woman who dared to escape from the flashes when she wanted is the sign of a true great artist, according to the main organizer of the exhibition, Cathleen Chafee, chief conservator at the AKG Art Museum in Buffalo, the institution to which Marisol left everything – her work and even some properties – because it was the first one that purchased an artwork from her.

“We are lucky to be able to put under the spotlight an artist who was forgotten but who deserves all our attention”, said Desmarais to La Presse, “not only because of her work’s aesthetic and innovative quality, but also because of her social and feminist engagement”.

I saw French-speaking young women intrigued by the large sketches on paper, a line of work totally unknown to me that resembles the audacious material of Latin American surrealists. My 10-year-old daughter was mesmerized by the dolls, the giant babies, the long wooden fishes with human faces, and the props and costumes Marisol made for contemporary ballet companies. And also by the fact that Marisol, though born in Paris, was Venezuelan. As much Venezuelan as my daughter, born in Caracas but raised in Montreal since she was a baby.

A double, liquid identity that for my daughter is normal, as it is for thousands or millions of kids of Venezuelan origin growing abroad, who have started to get a glimpse of the high culture produced at that troubled country of their parents, thanks to Venezuelan and non-Venezuelan donors, managers, curators and creators in the global arts circuit. Those people who rediscovered Marisol, but also Gego in New York or Mexico City, and Venezuelan academic music in many venues around the world. My daughter knows the conductor of her city’s symphony is Venezuelan. She’s used to find Rafael Payare’s face everywhere; now, when she’s also seeing the posters of the Marisol exhibition on the Montreal metro stations, she realizes that Venezuela is something else than her place of birth: a source of beauty and meaning that interests the world, not only of nostalgia and bad news.

──────

Marisol: A Retrospective is open at the MBAM in Montreal until January 21st. Details and tickets here. Next stops: Toledo (Ohio) Art Museum in March-June 2024, AKG Art Museum in Buffalo (New York) in July 2024-January 2025, and Dallas Museum Art (Texas), in Spring 2025.

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 22 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate