Venequia: How the Land of ‘Venecos’ Was Born

Mass migration led some of us to appropriate a surname with negative connotations created in Colombia decades ago, just like our ancestors seemed to assume the moniker that named our country.

It all started with a thread on Twitter (now, X). Lucho, a concerned Venezuelan architect living in Chile, decided to try to make sense of the new times (aren’t we all?). He started a very entertaining series of Twitter posts about the name of our country. He recounted the well-known story of the Florentine merchant and self-made explorer Amerigo Vespucci’s baptism of the territory of “Veneziola.”

I automatically remembered elementary school lessons about the explorers who sailed southwest under license by the Spanish crown and encountered an immense piece of land that was supposed to be the Indies. “We found a village built over a lake, like Venice,” Vespucci wrote years later in a letter used by German cosmographer Martin Waldseemüller to create the first known map naming America (1507) as a separate continent from Asia. It turns out that Venezuela is the center of a massive historical dispute.

Vespucci wrote about indigenous houses over the waters between the Peninsulas of Guajira and Paraguaná in a letter about his first voyage, now believed to be fabricated. The Florentine merchant was trying to take credit for the continent’s discovery by Christopher Columbus on his third voyage in 1498, where he arrived at “Tierra de Gracia” through Paria. Vespucci did visit the Venezuelan coast with Ojeda, but in 1499 (a year after Colón). The “Venezia” letter has created a confusion that has probably touched our very identity. Contrary to popular belief, the term “Venezuela”’s first actual record is on a map drawn by Ojeda and Vespucci’s fellow explorer and cartographer Juan de la Cosa in 1500.

The schoolbook versions of our history never discussed such confusion and also missed analyzing the final decision to adopt such a name. We sang Ricardo Montaner ‘La pequeña Venecia’ in actos cívicos as the modern take of our tale. We were taught to be proud without question. School and society framed it to make us believe in the beauty of being the picturesque version of a European destination. Mapa Juan de la Cosa. Detail. (1500)

An indigenous theory about Venezuela’s name is based on Martín Fernández de Enciso Suma de Geografía (1519). In the book, the first printed in the Spanish language about the discoveries of the New World, navigator and geographer from Seville describes in more detail the region and the people from the Gulf of Coquivacoa, including the name of a village in Lake Maracaibo where people were good and peaceful: “Veneciuela”.

This theory is backed by Spanish priest Antonio Vázquez de Espinosa’s Compendio y descripción de las Indias Occidentales (1575): “Venezuela en la lengua natural de aquella tierra quiere decir, agua grande, por la gran laguna del Maracaibo que tiene en su distrito…” (“Venezuela in the natural language of that land means ‘big water’ because of the great lagoon of Maracaibo”). The book, filled with detailed depictions of the New World, was written at the beginning of the 17th century and discovered, along with its revelation about Venezuela, in the Vatican libraries in 1929. Nevertheless, the indigenous theory “has never been backed by linguistic or ethnohistoric proofs,” as Venezuelan historian Tomás Straka replies in an email from Caracas.

The definitive authorship and meaning of the name have remained uncertain— a murky beginning for the history of a nation (empezamos mal).

Moreover, Christopher Columbus entered the land that is now Venezuela from the east through the Gulf of Paria just a year before the expedition of Vespucci, Ojeda, and De la Cosa. He called “Tierra de Gracia” –Land of Grace– what he saw in front of the island of Trinidad. How did we end up with the less flattering name from Ojeda and his crew? Well… thanks, Spain. Columbus’ well-known fall from grace from the Crown gave way to Vespucci’s claim of both the discovery of the continent and the naming of the place where this historic event occurred: Venezuela’s coast from Paria to Cabo de la Vela.

The new Spanish province was given the name of the Gulf of Venezuela first and then became the Capitanía General de Venezuela in 1777. We must have liked it, though (or we were too busy thinking about other enterprises). We kept it after our independence almost a century later, when it became República de Venezuela after a brief life as the Department of Venezuela of República de Colombia (la Grande). Nor Simón Bolívar nor José Antonio Páez considered updating our colonial name.

Most Latin American nation-states were formed around the same time during the tumultuous years of Ferdinand VII of Spain. Mexico, Cuba, Uruguay, Paraguay, Peru, and many other new countries decided to keep surviving names tied to their indigenous roots. Argentina kept its flashy colonial name (understandably so). Colombia, formerly Nueva Granada, took the term born in the Angostura Congress led by Bolívar, and Bolivia was baptized after him. The birthplace of la Gran Colombia and The Liberator remained named by European explorer De la Cosa. And the official version of its origin, a reference to a miniature copy of a port city in a faraway kingdom, whose citizens remained the habitants of a land of grace that kept a belittling name: Venezuela.

The OG “Venecos”

The first extensive news report on the use (or misuse) of the term “venecos” on the internet dates back to 2016. Colombia was one of the usual enemies of the Venezuelan government then; simultaneously, the migration to the country was increasing exponentially. Tensions were high when the Vice President of Juan Manuel Santos’ government said during an event for public housing projects in the neighboring region of Norte de Santander: “These are for the displaced living in Tibú. Don’t let the ‘venecos’ in here.”

The expression, used to refer to Venezuelans in Colombian territory, was answered with a formal protest from Caracas and very informal responses from Maduro’s government officials, including an expletive against Vice President Germán Vargas Lleras by Diosdado Cabello (como de costumbre). Nevertheless, the source of Venezuela’s offense was probably misplaced, and the use of the word by the Colombian official was perhaps inaccurate as well.

The popular versions of the term “veneco” originated in the 1970s. Recently enough to ask my father about it. My grandmother Trina was born in Cúcuta, Colombia. Her parents were exiles from Juan Vicente Gomez dictatorship, even though she denied the “geographical accident” of her birthplace her whole life. Her family, keen to Cipriano Castro, had proudly lived in the bordering region of Táchira in Venezuela for generations. Beyond the patriotic reasons of her claim, modernity and sophistication at the time and until the 1990s always meant east of the border; hence, when asked, my grandmother Trina said she was born in San Cristóbal, Táchira. Never Colombia.

Venezuela was the South American dream then and it became the first destination for Colombians leaving their country during the bloody civil war and sluggish economy of the second half of the 20th century.

“Venecos’ was the way Colombians jokingly –supposedly using a portmanteau of (Vene)zuelan and (Co)lombian– called their fellow countrymen who had migrated to Venezuela or the children of those migrants who acquired Venezuelan manners and accent (not my grandmother, though; she never accepted being born in Colombia, but my dad’s cousins called him “veneco” so he knew that there was Colombian blood in him). Therefore, “venecos” didn’t necessarily have a xenophobic tint but a way of asserting oneself with a hint of humoristic shame towards the other. A form of saying: “You are part of us, but you left, so you are different,” “We see you, but you are not fully us.” In a strict sense, Colombians in Venezuela are themselves the original “venecos.”

Eventually, the term mutated from a slightly disparaging remark towards Colombian-Venezuelans to a discriminatory expression for Venezuelans in Colombia. Nevertheless, it has been appropriated by the latter in the last five years. It is a humorous way to exert self-control over our new migrant image abroad. Historically oppressed groups have done the same to reverse the meaning of a discriminatory term in order to build group solidarity and neutralize its negative effect, for example African-Americans with the “N-word” or “queer” by the LGBTQ movement.

In fact, the Royal Academy of Spain had to publicly acknowledge in a tweet in 2018 that even though the word existed in the Diccionario de Americanismos as a belittling term, its connotation was not clear: “…Usted sabrá mejor si se emplea en su zona con ese matiz o no”, replied the official RAE account to a user.

What if the final mutation of the word’s meaning happened around those years?

First came the people and then their kingdom

According to the most accepted theory about the origin of the word “ticos”, the use of the term to refer to people from Costa Rica started during the war against the American Filibusters (1856-1857). Costarricans had the habit of misusing the morpheme “-ic” as a diminutive, and the fighters called themselves affectionately “hermaniticos.” Hence, they started to be known as the “ticos.” Their homeland was informally rebaptized with the dear term: “Tiquicia.” It is usually the case that one defines oneself when seen through the eyes of others, the same can happen with countries.

In 2016, the UN recognized the Venezuelan humanitarian crisis. That year, 6 out of every 10 Venezuelans lost 11 kilos. It also began a mass exodus, reaching around 7 million people today.

The nation-state, born in the 19th century out of the revolutionary idea of the “social contract,” crashed between 2017 and 2019 and all hell broke loose. The country became the territory of the pranatos, hyperinflation, hunger, corrupt billionaires, a memeable president, and misery. The absurd took over the daily life of Venezuelans and they took across borders the stories of two presidents at once, mega-blackouts and the unlikely with a hint of local humor.

Colombians started to receive hundreds of thousands of people from the other side of the border. And, maybe because that is how visitors from the territory to the east were historically called, the term “veneco” was reused and this time stuck (Venezuelans have a curious way of adopting unflattering terms). Now, venecos brought dramatic stories filtered, I am sure, by our people’s characteristic humor. I try to imagine the moment the first Venezuelan migrant passed by and heard something of the sort “ahí viene otro veneco” and decided to reply in a empowering exercise: “Ah, ¿con que veneco? Pues yo mismo soy.”

Maybe it is because most migrants passed through Colombia in those first years of the great exodus on their way to Perú, Chile and other South American countries and more recently on their path to Darién, but ‘venecos’ became mainstream.

So, if Venezuelan migrants are the “venecos”, what is Venequia? Strictly speaking, the term is a neologism formed by the root “Venec” and the suffix “ia.” Historically, some nations have used this formula to name their territories: Britannia was the land of Britons, Galia, Tracia, and Grecia all follow the same rule. It is also used to name fictional places that exist from a shared sense of belonging, like “Tiquicia” for the “ticos”.

In the case of Venecos, adding the suffix “ia” gives us Venequia, the land of Venecos. It is a term that has been popping up on the internet as of recently. This then leads to another question: Which land is referring to? If “venecos” are the ones leaving, what is Venequia? As with anything in Venezuela, there’s not one single answer.

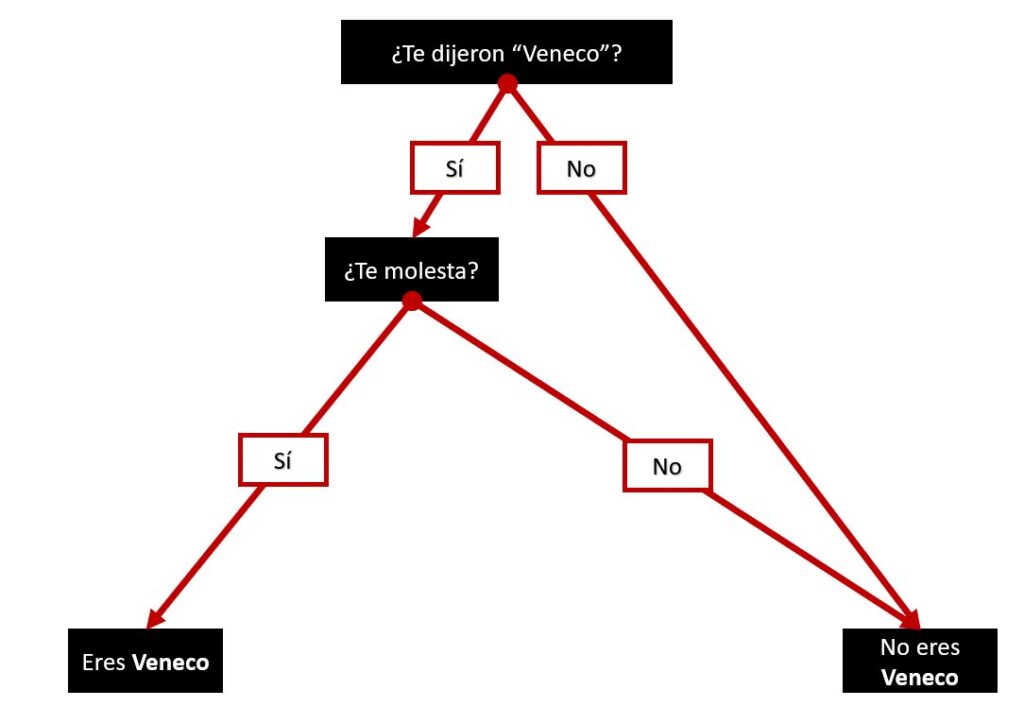

Venezuelans have appropriated the demonym “venecos” and are creating a nation around it. Both inside and outside the territory of their official Republic, Venezuelans are summoning “Venequia” in at least two ways online. First, the digital collective created by the diaspora, but more commonly, to refer to the dystopic reality back home. In the end, it seems, the “venecos” are the curious people from the land where magical realism turned dark. Postcards of this tribe are found daily on an X (former Twitter) profile feed called @venequismo, “where we can be venecos without judgment,” reads its bio, but judgment encouraged it is.

Comedy has become a way to exorcize our collective trauma by making a parody of ourselves and our circumstances. The phenomenon’s explosion in 2018 coincides with the spread of the term “veneco.” By then, George Harris had been sharing the Miami experience with an unapologetic Venezuelan accent for seven years. A group of comedians who emigrated during the collapse of Venezuela contributed to the formation of a new online audience. They served as neo-correspondents dispatching from varied territories and sharing the migrant experience. José Rafael Guzmán, a well-known comedian from Caracas, decided to live in the streets of Mexico City and share the homeless migrant experience online. Leo Rojas, Chris Andrade and Nacho Redondo founded ‘Escuela de Nada,’ a video podcast that started with the tales of the Venezuelans in Mexico City and soon became one of the most successful in Latin America. All the way to the South, Nanutria started capitalizing on his fame in the new Venezuelan community in Argentina and online with El Super Increíble Podcast de Nanutria.

A wave of views and spontaneous creators followed. “Venecos” became one of the topics for shareable content among Venezuelans to make fun of our character lows, charged with a traditional classist undertone. The term has been used as a self-disparaging escape valve that unites us, and a category that clearly discriminates. Online, “veneco” draws a line between the mess and the order, between the aspirations and the shame– a new inequality index born online.

A new shared sense of collective self is being born from the transformation and ownership of the migrant identity crystallized in the term “venecos.” Venezuela’s collapse is giving way to “Venequia,” a digital nation that includes the best and the worst of us—the absurdity and the shadows back home and the aspirations to be different abroad. Like the term “venecos,” only time will tell the true character of the new nation of Venequia and its people.

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 22 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate