Venezuelan NGOs Need (And Want) to Improve Their Performance and Management

A survey reveals Venezuelans NGOs grapple with organizational and financial challenges to sustain its operations, deepen its professionalization and gap geographic inequalities. But with the necessary backing and coordination, the social industry can strengthen itself and widen its impact

Breaking through a prolonged humanitarian crisis, Venezuelan NGOs have enhanced their capacities in recent years. Nevertheless, they are still limited by geographic inequalities and important organizational and financial challenges, as we found in a survey carried this year by our nonprofit Fundación S4V –which promotes public-private alliances and offers consulting to strengthen technical and articulation capabilities of NGOs in Venezuela.

While Venezuelan NGOs are reluctant to hand in detailed and updated information due to mistrust and potential regulatory threats to their operations, we managed to poll 134 legally registered NGOs in Venezuela out of the 260 that we originally contacted. The organizations that participated, distributed throughout the country, represent 13.4% of all active NGOs in the country, per data of our organization.

The survey, besides highlighting challenges, also painted a picture of Venezuela’s NGO ecosystem nowadays. For example, following a nationwide trend of social-geographic inequality, our study found out that most social organizations are located in Caracas and neighboring Miranda state (in comparison, only 12 work in Barinas and only 10 in Trujillo). However, there is also a significant presence of organizations with operational reach at the regional level in the states of Zulia, Bolívar, Anzoátegui, and Sucre.

The social industry has also bloomed following the country’s collapse. Most of the sampled NGOs were also created after 1999 (79,8%), with a growing trend of new social organizations created between 2016 and 2019: years in which the socioeconomic and humanitarian crisis of Venezuela worsened, creating a greater need for humanitarian assistance, and mobilizing the citizenry. In fact, there are two main areas of attention among the social organizations in the sample: 66% address education and 58% are focused on health. Likewise, the area of feminism and women’s care stands out, gaining strength as a transversal approach that crosses all care sectors and which now represents 48% of the organizations of the sample.

Similarly, children and adolescents at risk are the main beneficiary population among the social organizations that participated (71%). Other relevant beneficiary populations are women heads of households in vulnerable situations (53%), people with disabilities (48%) and pregnant and breastfeeding women (47%).

But the scope of beneficiaries NGOs can reach is not equal. In fact, only 7 of the sample organizations benefit more than 100,000 people and of this only 2 exceed a million Venezuelans. These numbers show that organizations with regional or national scope –which have projects financed by the United Nations, international cooperation and/or international NGOs– report a greater number of beneficiaries than organizations with local or community scope, which depend mainly on their own resources, private donations, or alliances with other national organizations. This suggests a gap in access to financing sources and in the management capacity of social organizations according to their operational and geographical scope.

Managing NGOs in Venezuela

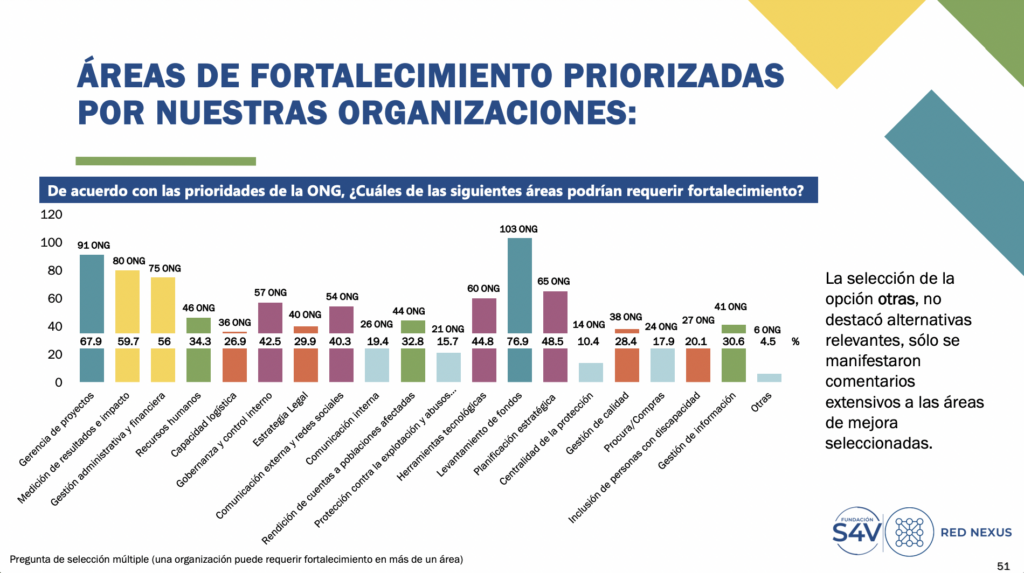

And geography isn’t the only widespread challenge in the social industry. Managing social organizations in Venezuela also poses significant financial and organizational challenges.

The primary concern revolves around their long-term financial sustainability. Secondly, administrative management is hindered by difficulties accessing and handling foreign currency bank accounts as well as facing overcompliance. Thirdly, the absence of an industry-wide vision has resulted in a lack of specialized sector data, limiting their ability to gather information. Lastly, there is a pressing need to address potential regulatory laws that could significantly impact their operations (even consider ceasing).

Our report also found out that the workforce of social organizations is largely supported by volunteerism, which is nine times the number of people who obtain some type of income in the organizations in the sample: or more than 26.200 volunteers in the sampled organizations. While this stresses the commitment and solidarity of citizens, it also poses a challenge for the professionalization and retention of human talent in the social industry.

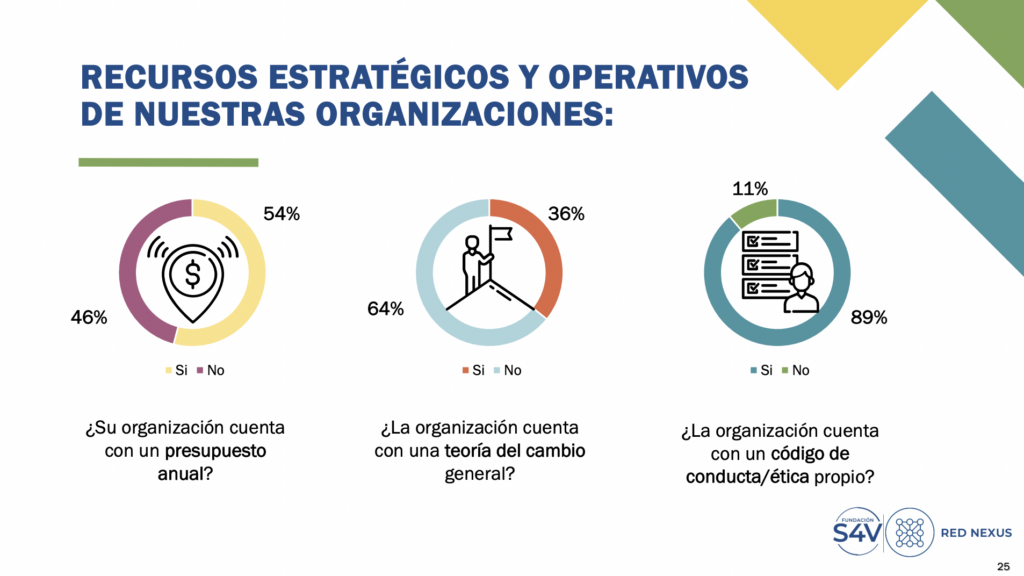

Nevertheless, the establishment of codes of ethics, accountability mechanisms for affected populations and policies against sexual exploitation and abuse in NGOs has increased in comparison to previous years. On the contrary, organizational theories of change –that help to identify and measure the short and medium-term changes and long-term impact– are lacking in most of the sampled NGOs (64%).

In fact, the indicators used by organizations to monitor and report their results are mainly focused on the quantity and characteristics of the beneficiary population, leaving aside other key aspects of organizational performance and strategy, such as quality, efficiency, effectiveness, sustainability, and innovation of their interventions. Similarly, there is little culture or intention of accountability and transparency towards the public. Very few organizations share management and/or strategic reports in their own media or digital platforms.

Most sampled organizations (70%) haven’t aligned their institutional strategy and evaluation system with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and their 232 indicators promoted by the United Nations. This is a lost opportunity to contribute to the global development agenda, as well as to make its work visible in the country and globally.

Are Venezuelan NGOs economically sustainable?

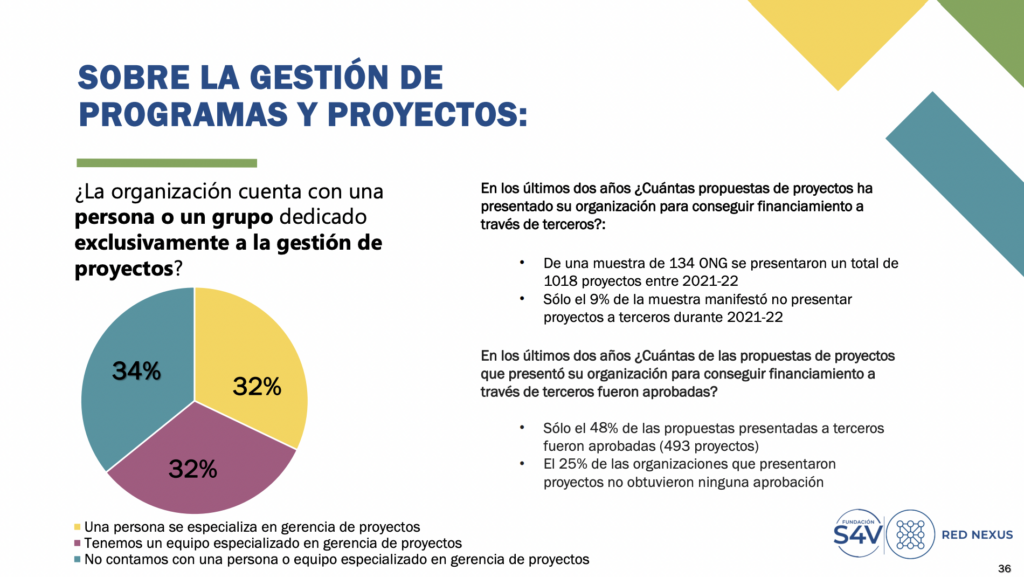

According to our survey, less than half (48%) of the project proposals presented by the sample organizations to third parties (private donors, companies, international cooperation, among others) for financing and donations in kind were approved and most organizations have few or non-specialized personnel in project management and fundraising. This evidences the need to continue strengthening the capacities of social organizations in project formulation and management and the organizations’ limitations to ensure quality and compliance in its objectives and commitments.

While most organizations want to access international financing, most that haven’t are outside Caracas and say they have a lack of access. This situation highlights the need to expand and democratize access to information and financing opportunities for social organizations throughout Venezuela.

Similarly, NGOs are not receiving financing to strengthen their organization, technical and administrative capabilities. This is limiting their potential growth and development and shows a lack of interest from financers in leaving real installed capacities in Venezuela through a common strategy that ensures the operational continuity of the social industry.

Currently, the most extensive and impactful organizations are those operating as implementing partners of the United Nations System in Venezuela and international NGOs with a presence in the country. These entities adhere to rigorous due diligence processes, continuous audits, and capacity evaluations. However, since they operate in project-based alliances, their financial sustainability is contingent upon the project’s duration (most of them are less than 12 months), the solidarity of major international donors, and the geopolitical priority of global conflicts. Venezuela’s inclusion in a protracted crisis may lead to diminishing interest from the international community over time.

NGOs want to improve

Yet, the high willingness of organizations to participate in civil society networks and coalitions –which favor articulation, advocacy and the exchange of experiences and good practices among the social sector– is noticeable. In fact, the survey resulted in more than 50 NGOs joining our Nexus Network (an initiative of the Fundación S4V to bring together national and local NGOs from all states of the country to share lessons learned, information on calls for projects, common challenges, promote alliances between organizations, among others), expanding its reach and diversity and ensuring that all participating organizations join at least one social development articulation network.

Since 2018, we have been collecting data on the performance of Venezuelan social organizations. Moreover, we have provided technical support to over 120 organizations nationwide. NGOs today possess enhanced capabilities compared to the initial data collection period. This affirmation is not solely based on their self-reports but has been observed on the field.

However, a prevailing sentiment among these organizations is one of isolation. Many feel disconnected and express a pressing need for increased support from authorities to secure safe access to communities, expand their coverage, and foster alliances built on trust. The commitment of the United Nations System and international NGOs to collaboratively shape a unified strategy for capacity-building in the social sector is duly acknowledged. Nevertheless, the call for engagement extends to the citizens of Venezuela, emphasizing the potential for these organizations to serve as committed institutions capable of jointly reshaping the reality for thousands facing dire circumstances.

Only some Venezuelans can identify at least five social organizations in the country actively driving positive change, according to data from our organization. While positioning oneself at the forefront of public consciousness is a challenge for the social industry, it is imperative to continue fostering trust in an often overlooked sector despite its unwavering efforts to assist millions of vulnerable people. This sector grapples with numerous challenges to sustain its operations and strives for ongoing professionalization. With the backing of authorities, the support of the citizenry, and collaboration with international stakeholders, this sector can further strengthen itself, scale its impact, and extend assistance to an even more significant number of people.

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 22 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate