Venezuelan Payroll “Benefits” Harm Employees And Push Companies to Break the Law

Labor benefits don’t necessarily benefit Venzuelan workers. When employers do the math, they realize they have to offer lower salaries so that the whole package becomes affordable.

In Venezuela, there are some laws and policies that seem sensitive because they are framed as instruments to “protect the vulnerable” when in fact they harm the very people they purport to protect. There’s a few examples of this: Our rent law and related policies make homeowners terrified of renting their property. We therefore have few listings and soaring rates in cities full of empty apartments.

Similarly, labor benefits don’t necessarily benefit workers.

Venezuelan law requires employers to provide generous benefits to workers, paid to employees for certain concepts in addition to their salaries, sometimes in contrived ways. When employers do the math, they realize they have to offer lower salaries so that the whole package becomes affordable. Most companies sidestep the benefits altogether by paying informally.

Ignoring the law—as has become common practice—works in the short term to increase workers’ incomes, but doing so places companies at risk, and makes a mockery of the rule of law.

So, given the country’s macroeconomic context, these benefits end up reducing wages, holding back job creation and promoting informality.

There are many regulations on labor in Venezuela and this article is not meant as a comprehensive review of them all. Also, many of our labor benefits are unambiguously good as far as I can tell, such as paid maternal leave and mandatory overtime pay. Instead, I will focus on some regulations that affect Venezuelans’ paychecks in a paradoxical way.

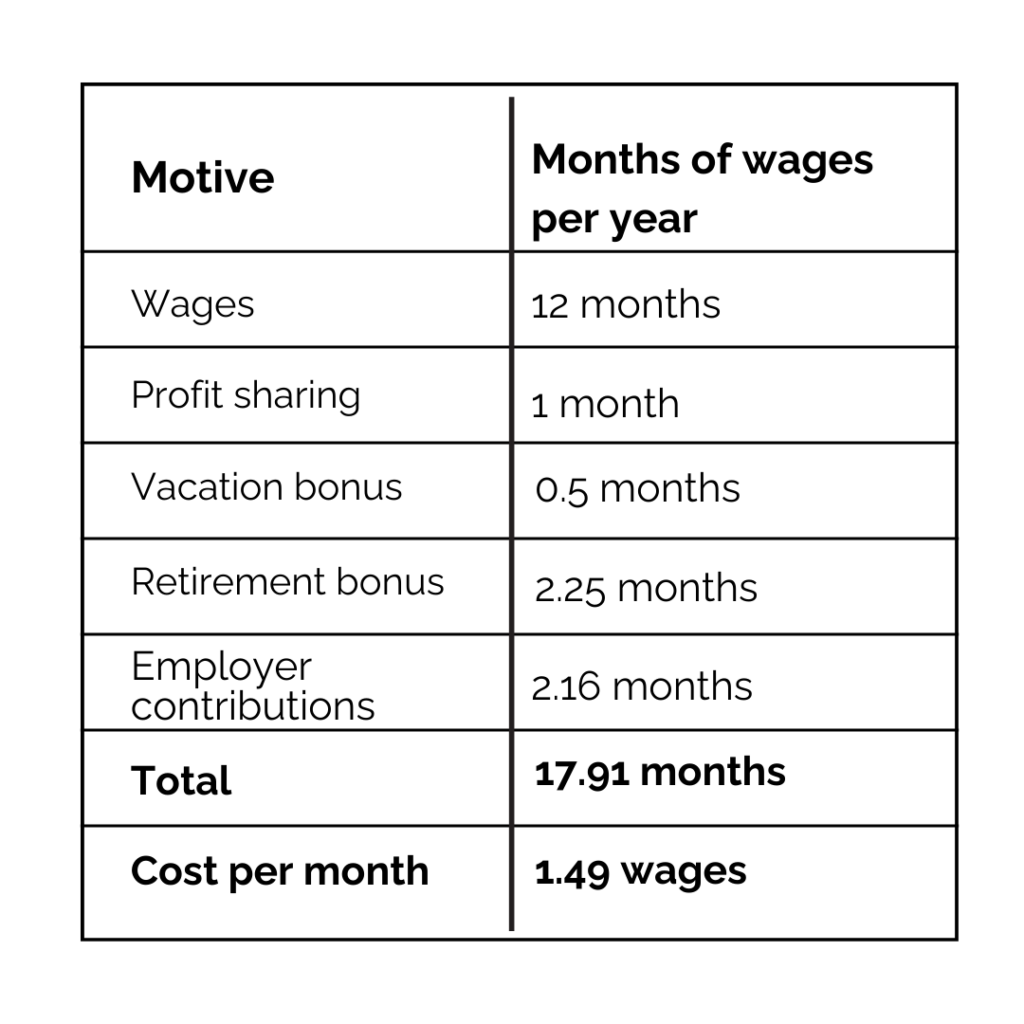

I will keep a tally of how much each benefit costs, so we can see how these “benefits” negatively affect worker’s salaries.

Profit sharing (utilidades)

Employers are required to distribute 15% of their profits each year to workers, by paying a bonus ranging between one and four months’ salary. They must pay at least one month’s salary even if there are no profits.

For our tally, let us say the cost of this benefit is the minimum, which is the amount usually paid: 1 month’s salary, per year.

Vacations and vacation bonus

Employees are entitled to 15 workdays per year of paid vacation, plus an extra day per year worked, up to 30 days. This works out to a generous 3-6 weeks of yearly vacations, in addition to national holidays.

Employees are effectively paid double for these vacations. On top of their usual wage, they are entitled to a bonus of 15 to 30 days’ salary as a vacation bonus.

To keep score, let’s stick to the minimum: Half a month’s salary, per year.

Retirement bonus (Prestaciones sociales)

This is the largest of the labor benefits and the one employers are most scared of. It is provided to workers upon leaving their jobs. Once an employee departs, they must receive one month’s salary per year worked at the company, on the basis of their latest salary. Profit sharing and vacation bonuses must be calculated as part of the salary.

To “save up” sufficient funds for the bonus payment, the employer is obligated to set aside half a month’s salary in an interest-earning fund every trimester. Therefore, two months worth of salaries must be deposited each year. Once the employee leaves, if the fund’s accrued value exceeds the amount of “one month’s salary per year worked”, the former employee will be paid the balance of the fund instead.

It is important to note that this benefit is paid in bolívares, a currency experiencing very high inflation from the moment the Labor Law (LOTTT) was enacted in 2012. That means that putting money into an “interest earning” fund is and always has been equivalent to shoving it into a furnace. Inflation was around 20% that year, 50% a year later, over 130.000% in 2018 and still over 100% last year. Needless to say, interest rates were never higher than inflation since the law was passed.

I wonder how many millions of dollars (or rather, their equivalent in bolivares) were wasted in this way over the past decade. It is no surprise that workers invent medical bills to withdraw as much as they can from their retirement funds each trimester (workers are allowed to withdraw up to 75% of these funds for medical expenses).

Anyway, let us add 2.25 months’ salary, per year to the tally. This is half a month’s wage per trimester, factoring in profit sharing and vacations.

Employer contributions

Most Venezuelans are hardly aware of these, but there is a smattering of labor-oriented state funds and organizations that get a cut from wages each time an employer pays – nominally to benefit workers. These are the following:

- Social Security: 9% of monthly wages or more for risky occupations. What do you get in return? A famously generous Venezuelan pension (around 4$ in December 2023).

- Mandatory Home Savings Fund (FOVH): 3% of monthly wages to be used for home purchasing, construction or improvement. Most Venezuelans are unaware of its existence, and I’ve never met anyone who’s been able to access this money.

- Unemployment Insurance (RPE): 2% of monthly wages meant to function as unemployment insurance. Again, this might be the first time Venezuelan readers outside HR departments hear of this.

- National Institute of Socialist Education and Training (INCES): 2% of monthly wages go to support the educational institutions managed by INCES. The Institute (formerly called INCE) has trained thousands of Venezuelans over the decades, and researching its current state is outside the scope of this article, but it is a 2% tax to be aware of, for good or ill.

So, let us add these contributions to our tally, amounting to 16% of pre-tax wages (inclusive of profit sharing and vacations) or 2.16 months’ salary per year.

Adding it up

I skipped a few benefits, such as food vouchers, in order to keep the math simple. I also based these calculations on the minimum amounts of each benefit. For employees with more tenure, or companies with larger profit shares, these numbers can get quite a bit higher.

With that in mind, let’s add it all up:

So, in order to pay for 11 months of work (A year, minus vacations and holidays), an employer must spend 18 months worth of wages, at minimum. This means that whenever companies comply with the law, they face a cost of labor that is 50% higher than the actual salaries paid to employees.

Much of this money is not received by the employee, but instead shoveled into the furnace of the retirement bonus guarantee fund or into various government organizations.

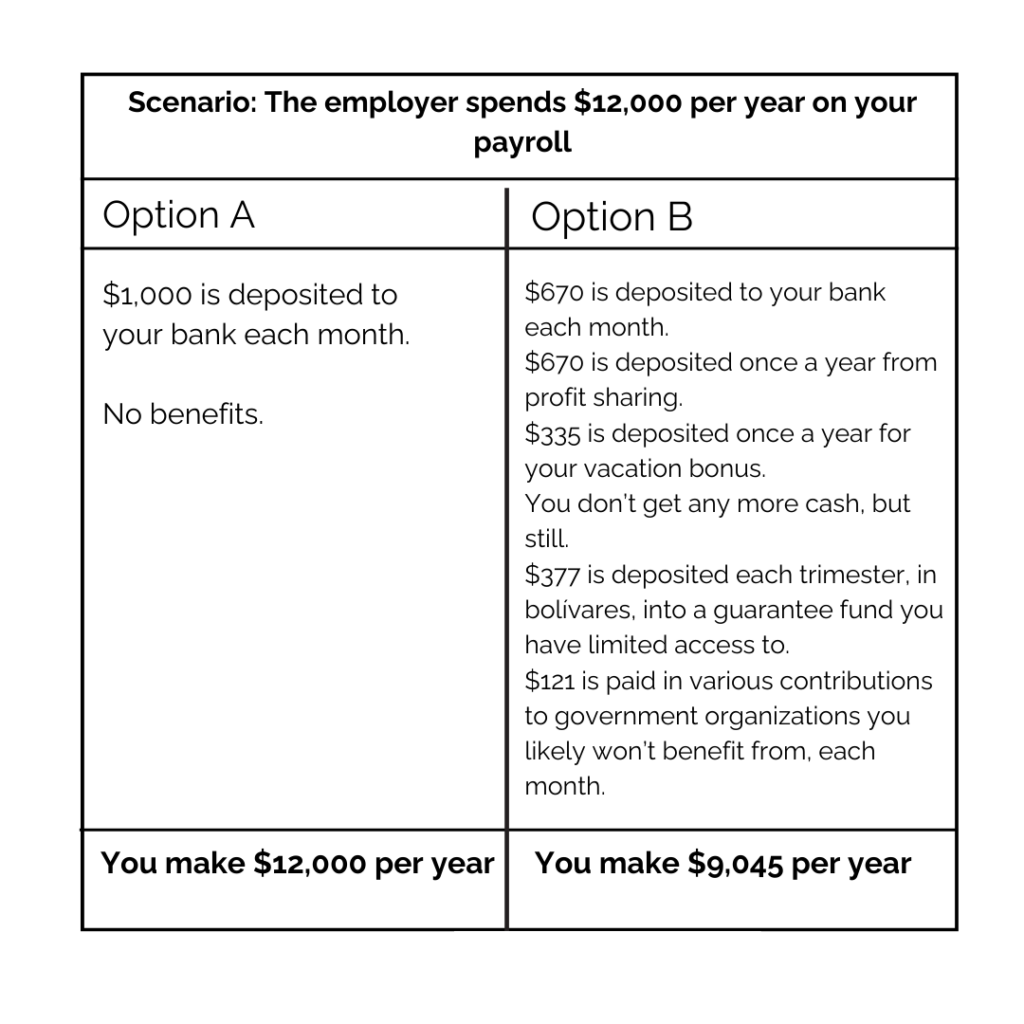

Let us see it from the other side. Employers only have a certain budget to spend on payroll each year, and this amount can be paid in various ways. In theory, employees could get it all in a monthly paycheck, but the law requires benefits and contributions, which affect how the money is apportioned. Now, from the worker’s point of view, which option would you choose?

The key thing to remember is that employers spend the same amount on you in either case. You can make more money without benefits than with benefits, and it’s all the same to your employer.

Also noteworthy: not all benefits are the same. The deposits to the retirement fund and the contributions to government organizations funnel money away from you, with no tangible benefit in most cases. The profit share and the vacation bonus simply change when you get some of the money, and do not affect your yearly income.

As a worker, you should know that these labor benefits are not “extra money” that was squeezed out of your employer by the law. Employers know in advance how much they have to pay for you and if they have to pay higher benefits they will pay lower salaries to compensate. These benefits are simply a redistribution of your wage, to a different point in time, or to a different recipient.

Trusting a blind eye

Since all of these benefits are calculated on the basis of the monthly wage, companies have resorted to paying a symbolic wage stipulated in contract (often the legal minimum), and providing the rest of employees’ compensation through “bonuses” constituting most income for workers. This drives down the value of labor benefits, but allows employers to afford higher monthly payments to their employees.

Now, the labor law unambiguously defines these predictable payments as “salary” and the companies implementing this practice are clearly in breach of the law. However, the government has stopped enforcing these regulations, likely because they understand that no good can come of that.

What would happen if the government took a stand against this practice and started enforcing the law? Many companies would quickly go bankrupt, finding themselves unable to increase their payroll spending by 50% or more overnight. Only the most profitable and least labor-intensive could survive such a blow.

Once the dust settled, companies would simply do the math for new hires and offer lower wages that they can actually afford. They would also stop raising the wages of existing employees and allow inflation to reduce their real salaries until they become affordable again.

In short, enforcing the Labor Law would cripple the private sector, eliminate a great many jobs, lower wages—impoverishing millions of Venezuelans—and destroy the little trust gained over the last few years in the possibility of doing business in Venezuela. It would be a temporary boon for some workers, but that illusion would quickly fade.

Most of the people I talked to in preparing this article were unconcerned about the issue of labor benefits, precisely because most companies don’t pay them and the government doesn’t seem to care. The sword of Damocles floating above us all didn’t leave such an impression on them as it did on me.

In the current context, the government can crack down on any company, at any point, and find them in breach of the Labor Law. This is an instrument for power and control that, when wielded, would break our economy.

A path forward

There is a principle at stake here as well: Laws should not be dormant beasts, ready to pounce. Laws should be the precise and stable guidelines of our rights and duties; designed to help us, not hurt us. We should obey them, and the government should conscientiously enforce them until they are changed.

When a law turns out bad, we should not ignore it: we should change it quickly, without tying ourselves in rhetorical or ideological knots. Politicians who want to earn “man of the people” points can defend these policies based on what they seem, but honest politicians have to oppose them based on what they are. Maybe the retirement bonus would have made sense in an economy with low inflation. We are not that, we have not been that for decades, so let’s get rid of it or replace it with something more sensible.

It is always troublesome to make a bad law, but it is very unwise to make a bad law that looks nice, for it will prove hard to change. I fear that is the case with our labor law. You must overcome a paradox to see the problem with it. But I believe this problem can be presented in a simpler manner to make a popular case. If I am right, eliminating these benefits will mean more money in workers’ pockets every month, protected by law. That’s a good selling point.

Ultimately, this is a decision for the legislature, and there lies some trouble. However, I believe we need to make space for policy discussions, taking for granted that political change must precede any implementation. There’s quite a list of laws and practices that warrant scrutiny, and it’s about time we start having a talk about the changes we want to see, and thus, to construct a mandate for our representatives.

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 21 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate