The Rise of the Apartment Caretaker

The flight of millions of Venezuelans after the country’s collapse and the state of the real estate market has resulted in strings of empty properties in Caracas. The result? A new profession

In Caracas, one of the consequences of massive emigration is the excess of empty or underutilized domestic spaces. However, these spaces are rarely abandoned or left to ruin. On the contrary, migrants’ decision to preserve local property after leaving the country has triggered practices around the protection and transformation of their spaces.

This context has led to the rise of a new figure in present-day Caracas: the caretaker (el cuidador), who embodies a series of practices involving maintenance, repair, occupation, and transformation of empty spaces.

These emerging dynamics occur at the intersection of emigration and collapse, creating new relationships between migrants and local actors, supporting migratory processes, and expanding transnational exchanges beyond the one-wayl flow of remittances. Likewise, these vacant spaces have been incorporated into the everyday dynamics of the city, serving as a support for new economic activities, expressions of solidarity, and forms of encounter.

Migrants’ homes have undergone transformations that adapt to various needs and opportunities―from providing bedrooms for children or community kitchens in poor areas or generating economic opportunities, to allowing young middle-class families to maintain social status by renting housing in affluent neighborhoods at low prices. But the caretaking practices and values particularly intersect with emigration, sustenance amid precarity, and the dynamics of the city.

Thus, in November 2022 –during fieldwork in Caracas– I interviewed various caretakers about similar aspects of their work, including their daily routines, their relationships with owners, the emerging networks between neighbors, and the spatial changes resulting from maintaining and repairing vacant homes. Interviews were recorded, transcribed, and thematically coded. It was important to contextualize caretaking not only within migrants’ changing needs and the personal trajectories of caretakers, but also within collapse as a daily experience that demands constant negotiations and adaptations, giving local actors agency over left-behind spaces and opening them to new possibilities.

According to municipal authorities who have carried out surveys among local residents, about fifty percent of all apartments [in Chacao] are vacant or under-occupied, a number that coincides with the estimations of property managers and real estate agents interviewed in late 2022

One of the caretakers whose daily routines I studied was Carlos Ancheta, who manages more than twenty apartments in the municipality of Chacao, the smallest and most socioeconomically affluent in Caracas. Due to its location and relative safety, Chacao is attractive for consular offices and, recently, international organizations that have established local offices during the humanitarian emergency. This factor has driven an increase in the real estate market in the area, accentuating the area’s status as an enclave with housing and businesses aimed at a public whose purchasing power exceeds the national average. The majority of Carlos’ tenants are foreigners residing in the city for short periods. The rest are young professionals or families who come to Caracas from other parts of the country, often for short stays and occasionally before migrating as well.

The apartments under Carlos’ care are in buildings constructed between the 1950s and 1980s. According to municipal authorities who have carried out surveys among local residents, about fifty percent of all apartments are vacant or under-occupied, a number that coincides with the estimations of property managers and real estate agents interviewed in late 2022. This high vacancy rate, together with a decline in living standards, the age of residents and the antiquity of buildings, contribute to the deterioration of these structures. This is reflected in out-of-service elevators, water supply problems, unlit hallways, and deteriorated facades.

The Caretaker

Carlos Ancheta’s work involves maintenance, protection, repair, adaptation, and changes in the use of the apartments. In fact, it showcases how the caretaker’s existence signals the collapse of state structures and legal frameworks related to employment and housing, as well as the boundaries between the formal and informal, the local and transnational. Moreover, the care of domestic spaces has become a scene for professional reinvention and is part of an economic and social ecosystem that has emerged in response to the void left by emigration. These practices extend far beyond homes; they include everything from personal objects and libraries to plants and pets, mobilizing resources and creating transnational support networks.

Studying Carlos’ work also revealed the multiple dimensions of the caretaker’s work, observed over several days as he opened, closed, watered, cleaned, supervised, waited, and negotiated in the apartments he cares for. Conversations that started in one apartment could be interrupted by a phone call or the urgency of reaching the next destination, where a painter awaited, or where we needed to arrive to coincide with the water-rationing schedule. As the dynamics inherent to the routine and the city shaped the interaction, the described themes emerged.

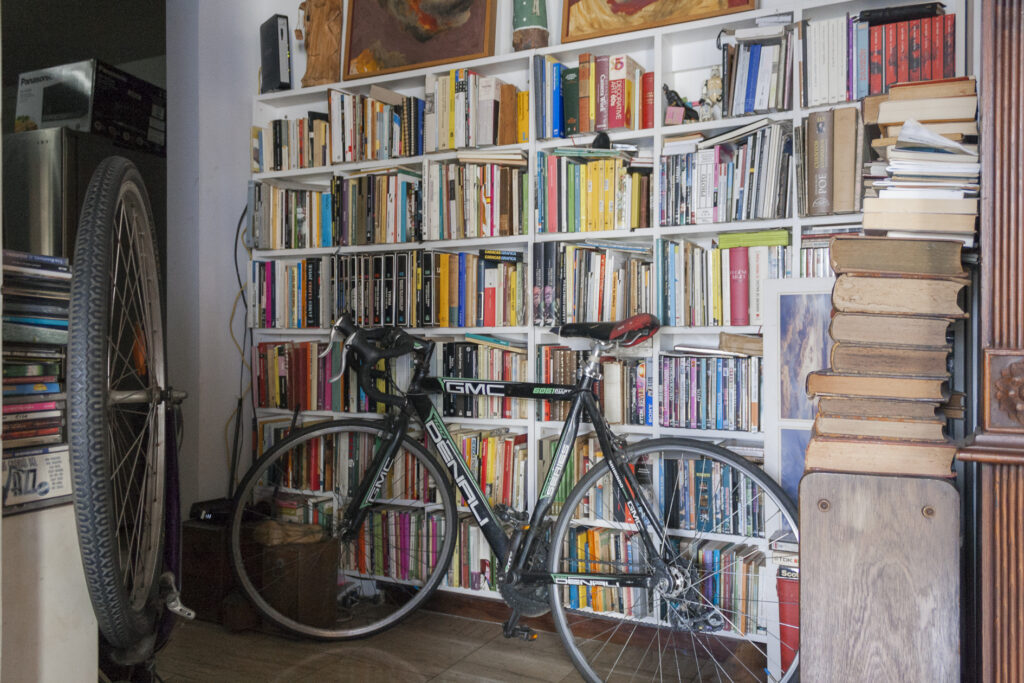

Carlos arrived in Caracas in 1991 to study architecture, and during his training, he became involved in the world of film and culture. He lives in the apartment of an exiled family. By the entrance, washing machines and microwaves are stacked, waiting to be repaired or installed. A gridded shelf organizes numerous sets of keys. “Welcome to the apartment of the diaspora,” he says, pointing to libraries, archives, and paintings. “These objects, left behind due to their dimensions, are gradually being taken out [of the country] or stored in warehouses.” The apartment is crammed with books, paintings, sculptures, and designer furniture that need maintenance or use while awaiting their final destination. In the master bedroom, the walls are decorated with black-and-white photographs by a renowned artist, and a Chaise longue LC4 peeks out from under a mountain of clothes. The secondary bedroom serves as a storage space for linen (sheets, towels, curtains, etc.) for all the properties. Thus, the apartment is simultaneously a residence, archive, storage room, and operations center.

The responses that have emerged to address the deterioration of public services include private alternatives and new forms of collaboration. In addition, management and maintenance tasks that were once the responsibility of management companies are now handled directly by condominiums, which communicate through chats and collect payments in cash. This collapse is generating new relationships. Carlos explains:

“I’m on the condominium chats of each of those buildings. I have to stay attentive to what’s going on. That involves getting to know each other and participating. Sometimes they request money for unforeseen events or bonuses for employees. If there’s an electrical failure, I recommend an electrician. Inevitably, bonds are formed (…) There are twenty apartments, so there’s always something to do. Trying to prevent damage requires constant supervision.”

I ask if he has a local team to support him. “I have a handyman, whom I need daily. Now and then equipment maintenance is required, so I generate jobs for third parties.” Carlos sees his work as a way of taking care of those who left and helping those who stayed.

Our conversation continues in an apartment that Carlos is renovating for rent, in a building from the 1950s designed by Klaus Heufer, a German architect who arrived in Venezuela in the post-war period. The apartment belongs to several siblings who need money to cover their father’s medical expenses. “It’s interesting,” says Carlos, “people leave the country for economic reasons, but once abroad, they expect the country to provide them with income.”

In the next apartment, Carlos takes photos of a piano and sends them to a potential buyer. His cell phone has become his primary work tool for managing repairs, selling furniture, paying bills, receiving international transfers, and interacting with owners, tenants, and neighbors. He then waters the plants and changes the linens. A tenant has just left, and he needs to prepare the apartment for the next one. “Moving libraries always involves negotiation. People don’t want their books touched and protect them zealously, but when renting, you have to make space,” Carlos adds.

The apartments under Carlos’ care are rented through Airbnb, making his work more profitable but also more demanding. Those who use this platform have high expectations and demand a level of attention similar to that of a hotel. “Lights must turn on, there can be no leaks, and everything must work”, Carlos explains, “It’s a constant maintenance job.”

Research on the urban impact of emigration has focused on cases in Europe and the United States where economic and demographic decline is tied to abandonment and ruin, like Detroit or post-socialist cities of Europe. This has resulted in a narrow visual imaginary and conceptual repertoire that falls short at describing some of the specificities of Venezuelan case. There, for a significant segment of the population that acquired property in times of economic prosperity and political stability, retaining homes in Caracas is more than an economic decision. It is imbued with symbolic meaning: homes are not merely individual place-holders but extend the values and livelihoods of the aspirational society that once defined the country. Locally, caretakers not only represent the interests of absent property owners but also experience the collapse on their behalf, exposing themselves to exhausting daily experiences, relying on informal support networks and other mechanisms of collapse.

In this context, rearranging spaces, dismantling libraries, safeguarding valuable pieces, or installing water tanks are actions that have a dual orientation: protecting a heritage and simultaneously extending its use. One makes the other possible. Perhaps this apparent contradiction, where the old and the new coexist and depend on each other is simply a manifestation of the new stage the city entered: not collapse, but its aftermath.

This text is an abridged and modified version of an article published in the architecture journal Diseña of the Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile. The complete text can be found here.

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 22 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate