Why the Andes and Other Parts of Venezuela Suffer from Rain-Related Disasters

A combination of global disruptions and local factors makes unusual rainfall more devastating, especially if we fail to learn from our own mistakes

The overflowing of several rivers and streams during the second half of June in the Andean páramo and some areas of the western plains has put Venezuela on alert. This marks the fifth consecutive year in which the country faces an emergency scenario linked to rainfall, prompting questions whose answers unfold on two scales: the global climate crisis and local planning.

What happened in the Andes and the Llanos?

The technical term used to describe the overflows of the Motatán, Santo Domingo and Chama rivers in the páramo is “torrential mudflow,” which means a river overflowing with not only large volumes of water, but also carrying sediments, rocks, debris, and any material in its path—making the flow dense rather than purely liquid, and thus more dangerous.

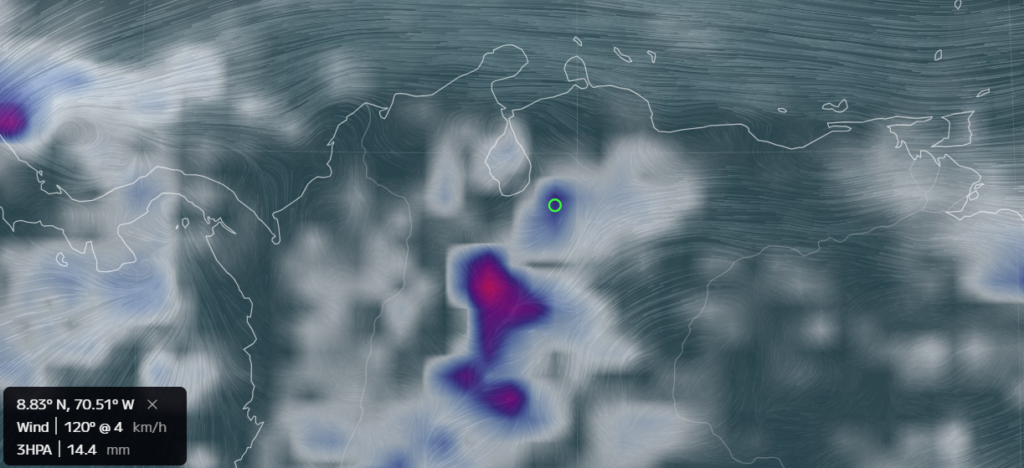

Although the páramo tends to be dry and present a rainfall deficit, similar events have occurred in the past. Even though it’s a region where it seldom rains, it’s not immune to extreme rainfall. In Apartaderos, for instance, the average rainfall for the entire month of June is 140 millimeters. On the most intense day of the recent event, that same location received 14 millimeters of rain in less than five hours—that’s 10% of the monthly average in just a few hours.

In the western Llanos, meanwhile, the upstream soils were already saturated. The same rains that caused the rivers to overflow in the páramo also triggered small streams in the foothills of Barinas and Portuguesa, which in turn caused larger tributaries—like the Ospino River—to overflow, damaging infrastructure and, so far, leaving one person dead.

Have similar events occurred recently?

Over the past five years, there have been uninterrupted instances of rivers overflowing in Venezuela. In September 2021, a tragedy in Tovar (Mérida state) echoed the disaster of 2005. In October 2022, a tributary of the Tuy River basin known as the Los Patos stream triggered the most devastating environmental tragedy in Venezuela in the last 15 years, in the town of Las Tejerías (Aragua state).

In 2023, various populated areas in Trujillo state—especially Monte Carmelo—were surprised by overflowing streams in May, leading to infrastructure and crop losses. In July 2024, the Manzanares River in Cumanacoa (Sucre state) overflowed, resulting in human, infrastructure, and economic losses.

All of these events took place during Venezuela’s rainy season, which spans from May to October.

Are these events caused by climate change?

There are no absolutes in this kind of scenarios. What we call climate change goes beyond extreme rain and droughts—it also involves air and water temperatures, wind patterns, ocean currents, and more.

So yes, these river overflows are related to global-scale climate changes, because all the factors just mentioned have been affected. But what matters most is their local context.

What do we mean by local context?

How we’ve occupied the land.

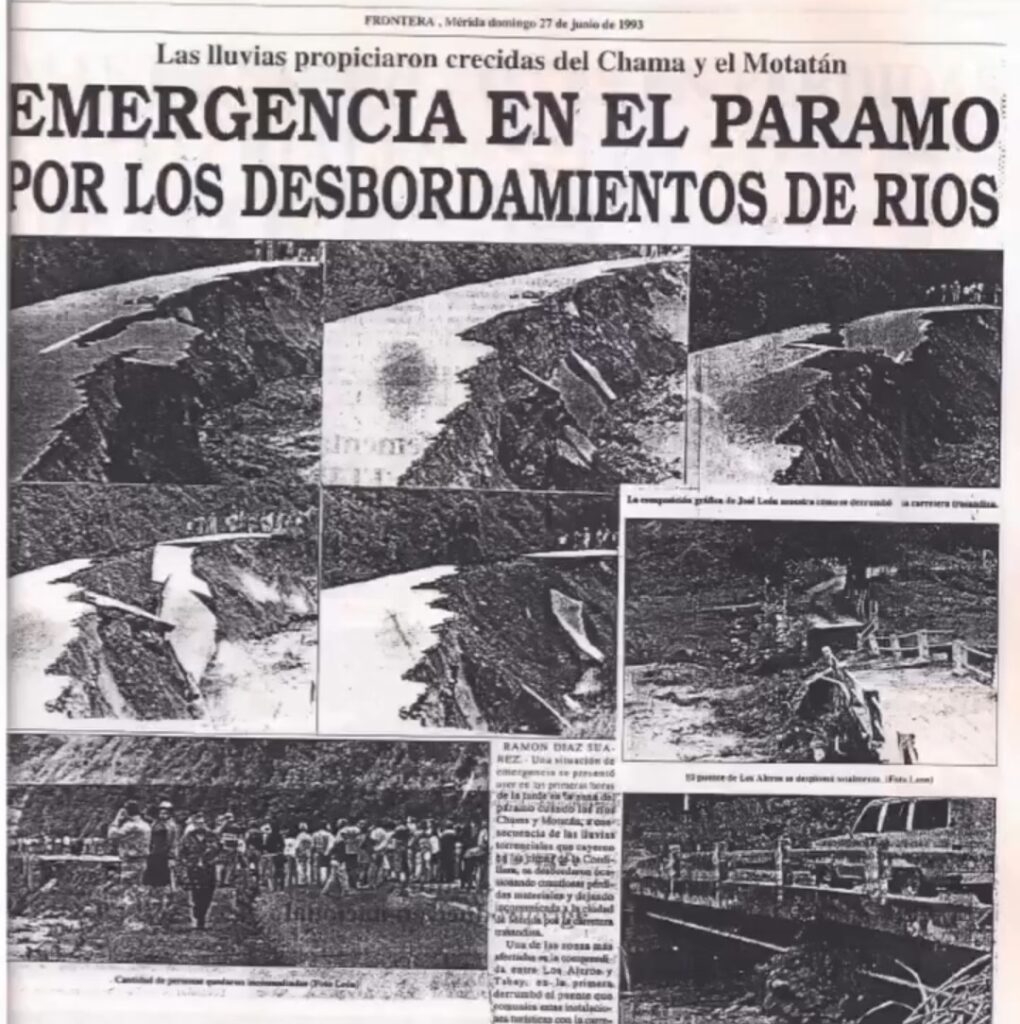

The last time something similar happened in the páramo was in 1993. In late June of that year, the Chama, Motatán, and Santo Domingo rivers also overflowed in a way almost identical to what we saw this year—but back then, the damage was less severe. The reason is that, even though the threat was the same, vulnerability was lower. We were less exposed because less land was occupied. Both infrastructure and farmland were less extensive and invasive.

Cumanacoa had a similar experience. The disasters of August 2012 and July 2024 were both triggered by the Manzanares River overflowing due to heavy rains. On both occasions, rainfall stayed within historical averages—but in 2012, 1,200 homes were flooded, while in 2024 that number rose to 6,000.

This shows that, if the rains that caused recent overflows are comparable to those that caused overflows in the past, the real emergency lies in the increasingly aggressive way we occupy rivers and their natural floodplains.

Which areas are most at risk?

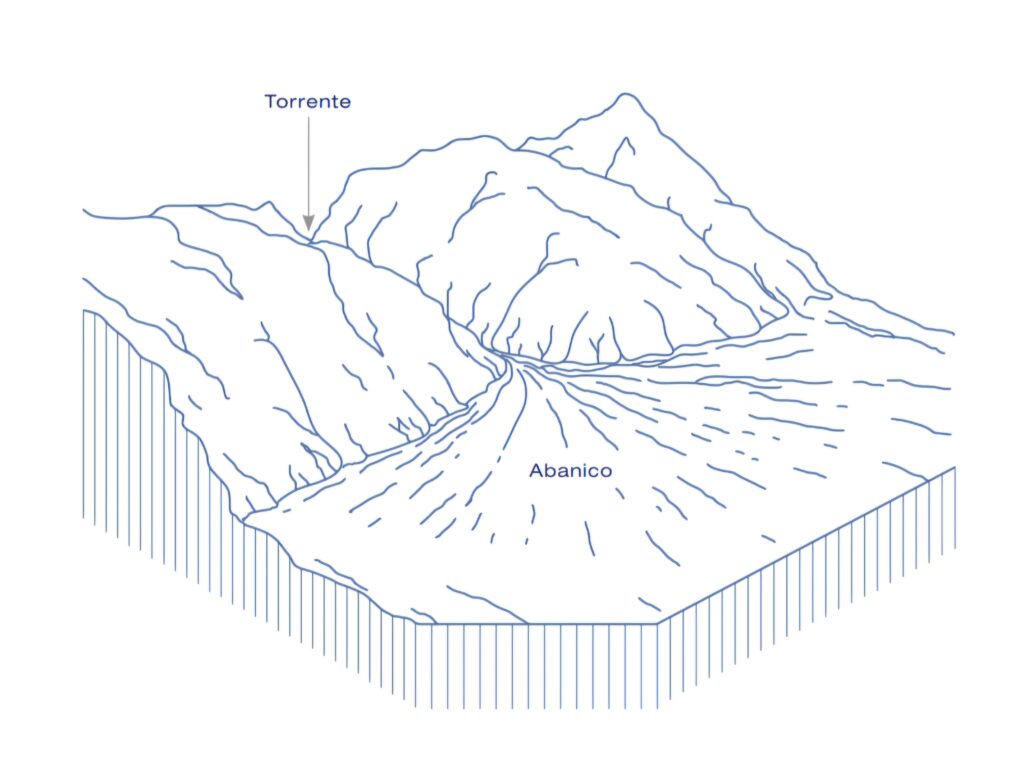

Most of the populated areas in Venezuela’s coastal-mountain region—the most densely inhabited part of the country—are built on landforms known as alluvial fans. Tovar, Las Tejerías, Monte Carmelo, Cumanacoa, and much of the Andean páramo sit on alluvial fans.

These locations are characterized by being nestled at the base of mountains and having relatively flat terrain. They are ideal for farming, as rivers deposit nutrient-rich sediments from the mountains in their soils. Their flatness also makes construction easier.

Venezuelan geomorphologist Carlos Ferrer Oropeza describes alluvial fans as “dangerously safe places”: they offer advantages for settlement and agriculture, but they also pose serious risks.

When a river overflows, the alluvial fan is the most dangerous place to be—it’s where the flood spreads out and unleashes its full load of debris at high speed, destroying everything in its path. It’s the natural outlet for any mass movement.

What’s the solution?

There’s no single solution. Just as floods depend on local factors, the solutions also rely on specific contexts, institutional will, and community action.

It’s unlikely that spaces like alluvial fans—with all the benefits they offer—will stop being occupied. But to reduce the risks of doing so, it’s crucial to understand the threats and reduce vulnerabilities.

What triggered the Los Patos stream flood in 2022 was the extraordinary rainfall. But what devastated Las Tejerías were long-standing vulnerabilities: deforestation in the headwaters and valleys of the basin, construction dangerously close to the river, lack of flood control infrastructure (like torrents and overflow channels), and poor maintenance of existing structures.

In the other five events of the past five years, the pattern was more or less the same.

The response must go beyond picking up bodies and clearing rubble. We need to institutionalize two key practices: environmental planning and land-use regulation. These go hand in hand and are not mutually exclusive.

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 22 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate