A Silent Emergency Is Unfolding on the Colombia-Venezuela Border

Two migratory flows converge around Cúcuta: one entering, one leaving. The lack of international humanitarian support could have devastating consequences

The images of thousands of people stuck on the Venezuelan side of the Simón Bolívar International Bridge, waiting to enter Colombia, are no longer common. Nor are the crowds of people walking en masse, as seen years ago. But those who still cross through this area now find themselves in near-total vulnerability. Of the 20 shelters that once supported Venezuelan migrants along the route between Cúcuta and Bucaramanga, only three remain. The places that once offered guidance, shelter, and a chance to rest and regain strength before continuing the journey are gone.

Volunteers still working in the area warn of a “silent emergency.” Colombian President Gustavo Petro warned in April of a potential new wave of Venezuelan migrants, this time, fleeing the migration policies of Donald Trump.

Humanitarian workers warn that if a new wave of mass migration occurs, no one is prepared to handle it: there’s no money, no resources, and no national or international support. A study published on May 27, projects that nearly 5% of Venezuela’s population has already decided to migrate in the next six months.

Along the route from Cúcuta to Bucaramanga, humanitarian presence has all but disappeared. Of the 17 international agencies that once operated in the area, only three remain, and their aid is far from enough for the hundreds of people still crossing the Simón Bolívar International Bridge. Additionally, there’s a growing flow of people heading back to Venezuela.

“Suddenly, the aid workers began to leave. I think it was around 2022, when the war in Ukraine broke out. They told us there were more important things to attend to, so they left,” recalled Ronald Vergara, a Venezuelan migrant who lives along the Cúcuta-Pamplonita road and runs Hermanos Caminantes. This shelter, one of the few still standing in the area, is located 49 kilometers from the Simón Bolívar International Bridge, a traditional departure point for Venezuelan migrants heading south. It used to accommodate 200 people per day but now can assist only 20 migrants at best.

Ronald went from working with 40 volunteers at his shelter, almost all recruited through international cooperation, to being accompanied only by his wife. The two of them cook arepas to give to the migrants who pass by. The meals that were once prepared by some organizations no longer exist. Ronald himself acknowledges that some walkers decide not to stop at his shelter when they see it’s almost empty.

There are several reasons to explain why dozens of international aid workers have withdrawn from the migrant route on the Colombian side. The journey of Venezuelans on Colombian soil begins in Cúcuta but has various destinations. While some stay in that city, others go to Bucaramanga, and some continue on to Bogotá and Medellín. Many even end their journeys in Ecuador, Peru, or Chile. However, Colombia remains the primary destination for Venezuelans.

Still the number of migrants traveling south has been low for at least two years. This coincides with the rise of the Darién route toward the United States.

“At first, the vast majority of migrants who crossed were headed south or to another part of Colombia. But in 2022, people didn’t stay long in Cúcuta because their ambition was to pass through the Darién to try to reach the U.S.,” explained Adam Isacson, a member of the Washington Office on Latin America (WOLA).

Ronald Vergara himself recalled that international aid workers used to ask him to try to persuade migrants not to head north. “They asked us to remind them how dangerous the route was and that there was no need to take such a big risk to reach the United States. They should choose other paths and be more patient.”

Between 2022 and 2024, nearly 700,000 Venezuelan migrants walked through the Darién jungle hoping to reach the United States. This shifted the main migration routes. Walking the road that connects Cúcuta to Pamplona was no longer a priority. New access points had emerged along Colombia’s coast, particularly the towns of Capurganá, Turbo, and Necoclí, the three main gateways into the Darién. Now, the same paths that were once used to leave are becoming routes of return for those heading back south through the continent.

Although aid workers remained around Cúcuta until 2024, they noticed that support was more urgently needed at the entry points to the Darién Gap. Ronald Vergara recalls that the first major cut in international aid to the area came on August 31 of that year, when World Vision, one of the organizations that most supported both migrants and volunteers, withdrew.

That withdrawal didn’t just happen near Cúcuta. Organizations left in other areas as well, Vergara said. Before August 31, there were buses and trucks available to transport migrants to various Colombian cities. This benefit was one of the first to disappear when September began. However, there were still resources for other types of aid—at least for a few more months. But that support finally collapsed in January 2025, when Donald Trump returned to power.

While he had warned he would deport millions of migrants, he also focused on cutting the funds that flowed from USAID to the rest of the world. USAID’s presence accounted for 42% of global humanitarian aid. Colombia was the Latin American country receiving the most from the agency (around $400 million annually), mainly allocated to humanitarian and migration-related assistance.

However, the new administration decided to conduct a thorough review of USAID’s spending. Although it is technically independent, it receives funding through congressional approval. The Trump-ordered investigation resulted in USAID’s dissolution and the appointment of Marco Rubio (the Secretary of State) as the organization’s interim director. In his first statements, Rubio announced he would slash 83% of USAID programs.

So, how does that impact Venezuelan migration? Ronald Vergara put it bluntly in an interview with La Hora de Venezuela: “The U.S. government’s decision brought everything down. Everything stopped immediately. All services. Then I got emails from aid workers explaining that their operations depended on the U.S. budget to stay afloat.”

By early 2025, Dutch organization SOA had the strongest presence along the migrant route from Cúcuta to Bucaramanga. They supported humanitarian workers with food, technical assistance, and health care. But after their departure, that stretch—still crossed by hundreds of people each month—was overtaken by isolation.

César García is Venezuelan. He heads the foundation Aid for Aids, which is affiliated with the Fundación de Venezolanos en Cúcuta (Funvecuc). His location is particularly strategic, just meters away from the Colombian entry point at the Simón Bolívar International Bridge. In other words, César and his foundation are among the first to provide aid to migrants. However, his ability to help has also declined. Where he once could offer meals, shelter, and even bus tickets, now he can only provide drinking water, personal hygiene stations, and blood tests for detecting sexually transmitted infections.

“We see that the emergency continues. It’s constant. Even if it looks different now, the emergency is ongoing. It hasn’t stopped,” said César García from his workspace in Cúcuta.“Of course, if you’re seeing 500 people a month, it seems like nothing compared to the days when the same number would be stuck on the bridge in a single day—or even a thousand,” he added, noting that the monitoring data collected by organizations still fails to grab the attention of the state.

The people who arrive at Aid for Aids have different destinations. Some seek to stay in Colombia, while others head to Peru or Ecuador. One striking aspect of this migration flow is that most have already migrated once, returned to Venezuela, and are now leaving again. There are even cases of people recently deported from the United States.

“A month ago, two people who had been deported arrived here,” García recalled. “They were taken back to Venezuela, escorted by the police. They were placed under a presentation regime, skipped their first hearing, and headed for the border almost immediately. They were on their way to Peru and said things would be better there than in Venezuela.”

During La Hora de Venezuela’s reporting trips in and around Cúcuta, dozens of people were seen taking the migrant route, but in the opposite direction, back to Venezuela. Sometimes on foot, sometimes by bus, people had various reasons for returning to their country of origin.

While more people are still leaving Venezuela, García noted that in recent months, the number of people returning has nearly matched those leaving. That presents its own urgent challenges. “When a family of five with children shows up after walking for three days—exhausted, hungry, and dehydrated—I look at what we have here and realize we can’t help them the way they need,” García explained.

According to data from Colombia’s migration authority, there are two main routes used in this reverse flow: by plane and by risky maritime routes. The latter has already seen multiple accidents, deaths, and disappearances so far this year. The agency also reported an overall increase in border traffic compared to early 2024.

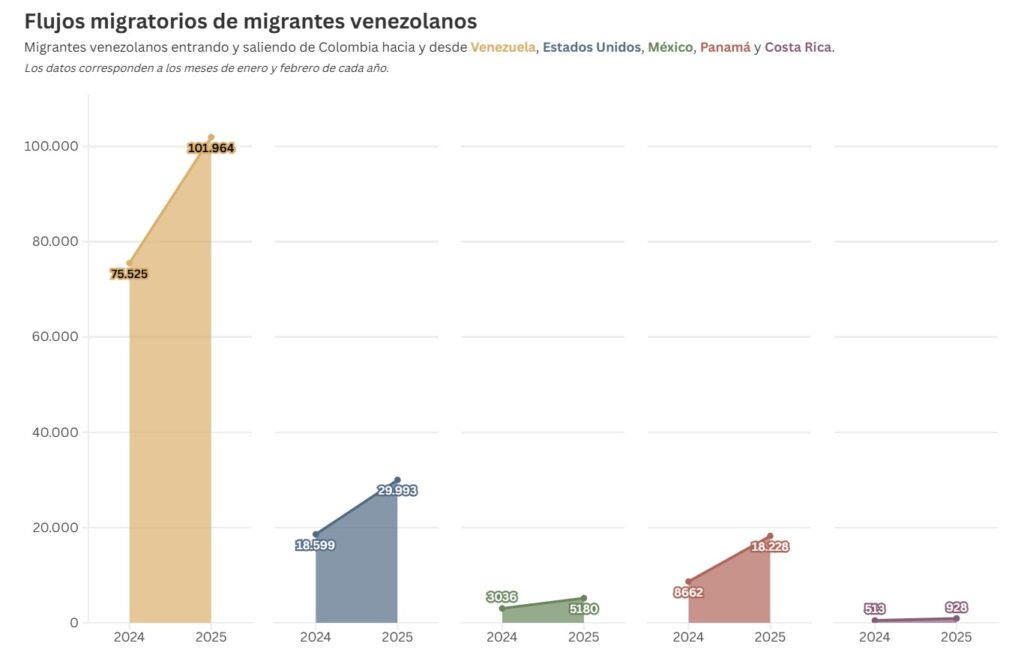

“In general terms, the entry and exit records show that in January and February of 2025, Venezuelan migration flows increased by 41% compared to the same period in 2024, highlighting the emergence of this new migration dynamic,” said Migración Colombia in a report published on March 10.

On the edge of Highway 70—the same road that crosses the department of Norte de Santander from Aguachica, in the department of Cesar, to the Simón Bolívar International Bridge—a family is walking. A young man wearing a cap and shorts, carrying two bags. A woman with long braided hair. Three children. And, noticeably, a white dog, worn out from the journey.

They are Venezuelans heading back to Venezuela. They stopped to rest at the side of Highway 70, about three kilometers from the exit of Colombia and the entrance to San Antonio del Táchira. Kleiver Javier Díaz is 23 years old. In his left hand, he firmly holds the leash tied to his dog. But in one of the two bags on his back, there are at least three puppies. “They’re migrant puppies, because they come from the southern border,” Kleiver says, laughing.

They have been traveling for three months from Argentina to Venezuela. Their goal is to reach the city of Guacara, close to Valencia. The family is exhausted, and their faces show it. They are also upset because just a few weeks ago they were robbed by other Venezuelan migrants on the border between Bolivia and Peru.

“We barely had anything with us. We bought the tickets, and the rest of the money we sent to Venezuela. The little we had was taken by some of our own people,” recalls Kleiver’s wife, who asked not to be named.

In Buenos Aires, Kleiver worked in construction and was doing okay despite xenophobia and discrimination. He lived for three years with his family in the Argentine capital. Now, they have decided to return with an uncertain outlook.

“We don’t know exactly when we’ll arrive. The idea is to get there, see family, and figure out what we can do. We are returning for them. My mom works sweeping streets and can help me find a job, but first I have to get there,” Kleiver Díaz said.

This family recalled that they had no shelter along the way through Colombia. However, they did receive aid kits in places like Pamplona, Chinácota, and Los Patios. These kits, delivered in blue bags, contain food and hygiene supplies to help people keep walking.

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 22 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate