The Nobel Peace Prize and the Burden of Democratic Struggle

Examining the Prize’s history and outcomes for laureates in akin contexts helps assess how it may affect María Corina’s leadership

On December 10th, far away from Caracas, the Nobel Peace Prize ceremony was held at the Oslo City Hall, a great moment of global moral clarity, as it is seen around the world. Among all, the Nobel Peace Prize is the most political in nature, and probably the most misunderstood. Handing it to María Corina Machado was not without controversy. Some argued that peace has yet to be achieved, others maintained that the struggle for democracy in Venezuela continues, and a few went so far as to claim that Machado was calling for war and escalating the conflict.

Despite that criticism, the Nobel Peace Prize recognizes Machado’s struggle to keep alive the flame of democracy under a dire authoritarian context. It certainly arrived at the most dangerous moment of this political process. But this begs the question: what does the prize being awarded to Machado tell us about the Venezuelan struggle for democracy—and what is dangerously obscure about that?

To begin elucidating this question, it is important to keep in mind that the Norwegian Nobel Committee recognizes struggles, not outcomes, and its decision to honor Machado is less about Venezuela’s democratic future and more about explaining why the international community chose to intervene, symbolically and morally, in this particular moment in history.

The state of democracy at the moment of recognition

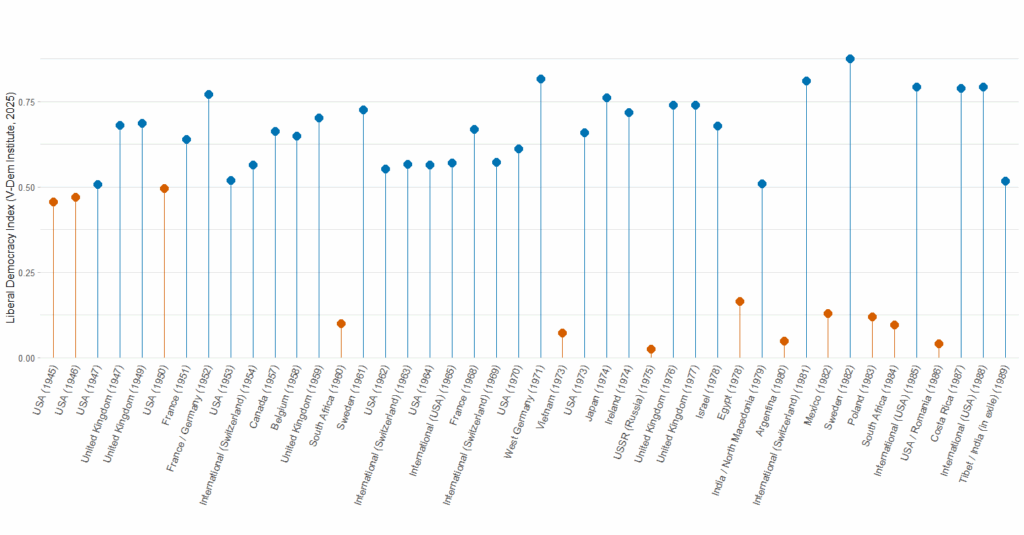

It is difficult to establish a relationship between liberal democracy or democratization processes and the Nobel Peace Prize, but a trend emerges in the following figure.

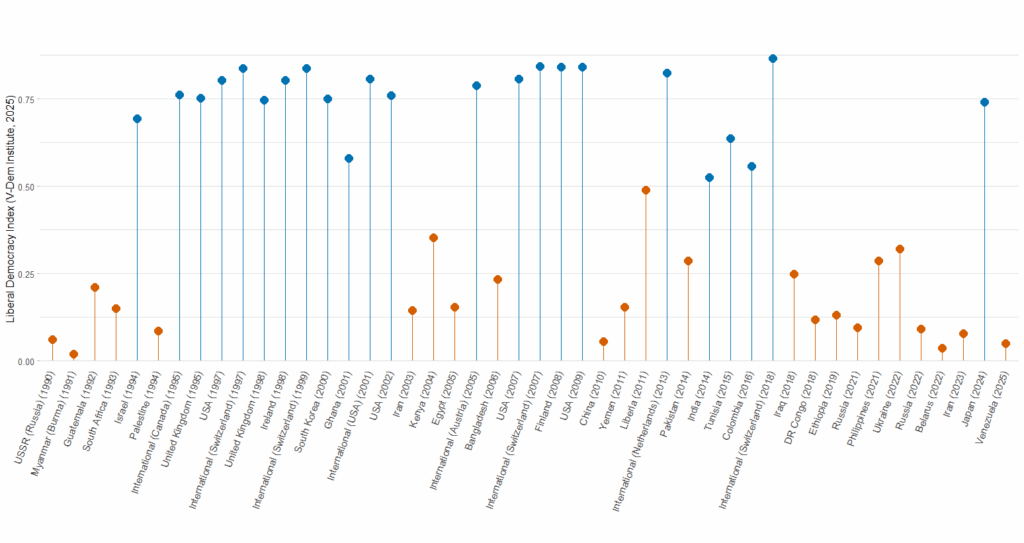

After major conflicts like World War II or the Cold War, leaders from established democracies were often awarded, but there are also periods when laureates come from low-democracy or authoritarian contexts. In this sense, the Nobel Prize functions as a moral intervention when institutions have failed the people, as seen in the second figure.

This trend is evident in the last 15 years of the Nobel Peace Prize, which has been awarded to figures from authoritarian contexts such as Russia, Belarus, Iran, and, most recently, Venezuela in 2025. Seen in this light, Machado’s award fits a more recent Nobel pattern: it is granted not after democratization, but during the struggle, before a political transition has occurred.

We need to take the prize’s symbolism seriously. It is not necessarily about political power but moral authority. The Norwegian Committee increasingly rewards symbolic leadership rather than governing capacity. That is why earlier recipients often came from countries with strong institutions and democratic regimes, in a more celebratory context, whereas more recent laureates represent civil resistance against authoritarian regimes, boosting morale among pro-democracy forces and their ongoing struggle.

In this sense, María Corina Machado’s Nobel Prize validates peaceful protest and nonviolent resistance, rather than placing a bet on a potential presidential candidate.

Power after the prize? Three precedents

More recently, people wonder what the fate of María Corina and the struggle for democracy in Venezuela will be after receiving the Nobel Prize. We can look at three past laurates who also sought to expand human rights and pave the way for a democratic future.

Especially in light of the detention of Narges Mohammadi, the 2023 Nobel Peace Prize laureate in Iran, and the release of Ales Bialiatski, the 2022 laureate in Belarus—the same week Machado received the award—concerns about her safety are heightened.

A Nobel Peace Prize does not bring about transitions, nor does it replace domestic institutions. Instead, it raises the international cost of repression, protects civic mobilization, and fixes moral responsibility on the regime.

From these precedents, three scenarios emerge for Machado’s path:

The first scenario is the “good” case: Nelson Mandela. In 1993, the South African leader was awarded the prize amid a negotiated transition already underway, after being in prison for almost three decades. By forming a wide coalition, Mandela and his party built a strong case for democratization, in conjunction with international pressure. The prize came just one year before winning the presidential elections. In this case, the Nobel came during the path to power.

The second scenario is the “not-so-good” case of Aung San Suu Kyi, from Myanmar. When she was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1991, it was a time of moral resistance very different from Mandela’s case. She would finally reach power 24 years later, illustrating that political authority does not follow immediately from the award. After the transition from a military junta to a more democratic regime, and after her party won reelection in 2020, her government was toppled by a coup d’etat that sent her back to prison with a 27-year sentence. The new military junta stopped the democratic transition and she was banned from holding office. She has also been criticized for her unwillingness to condemn campaigns against an ethnic minority. This case demonstrates that even with a Nobel Prize and electoral success, democratization is fraught when military dominance and deep ethnic conflicts remain.

And the third scenario is the “bad” case: Guatemala’s Rigoberta Menchú. Menchú received global recognition for her work defending the rights of indigenous communities in Guatemala. It is a “bad” case not because something happened to her—she is still active—but rather that her two presidential campaigns, in 2007 and 2011, were unsuccessful. Menchú’s experience is a good example of the prize’s inability to actually produce palpable outcomes in domestic politics. International recognition does not automatically translate into domestic power.

When things are dire and hope is needed

In Venezuela, liberal democracy is at its lowest, as shown in the second figure. The Nobel Prize Committee awarded the prize because of Machado’s activism in nonviolent resistance, electoral organization, and keeping the flame of democracy alive in an authoritarian regime. The Nobel here amplifies the cause of Venezuelan democracy amongst international elites, but does not resolve the long-standing power imbalance.

A Nobel Peace Prize does not bring about transitions, nor does it replace domestic institutions. Instead, it raises the international cost of repression, protects civic mobilization, and fixes moral responsibility on the regime. It is more of a symbolic intervention. Machado did not receive the Nobel because Venezuela is transitioning to a democracy, not even because that outcome can be guaranteed under the current circumstances. She received it precisely because Venezuela’s democracy is at its lowest, and the cost of dissenting at home carries extreme risks. This has been the trend among laureates over the last 15 years.

It is also important to caution against messianic expectations. Democratic transitions result from collective action. Any future democratization process and its subsequent consolidation must emphasize society over saviors—a mistake Venezuelans have made in the past and must avoid once and for all.

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 22 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate