Keystone XL is Back On. Venezuela Should be Afraid. Very Afraid.

President Trump wants to build the Keystone XL Pipeline after all. This is a disaster for Venezuela's energy strategy, and one that makes retaining control of Citgo not just important, but imperative.

As one of his first acts in office, President Trump signed an executive order signalling that the Keystone XL pipeline is on again. For me, it’s a little awkward: no other issue puts the interests of my birth country and my adopted country so directly at odds.

Not to put too fine a point on it: Keystone XL is a kick in the nuts Ottawa has aimed milimetrically at Caracas.

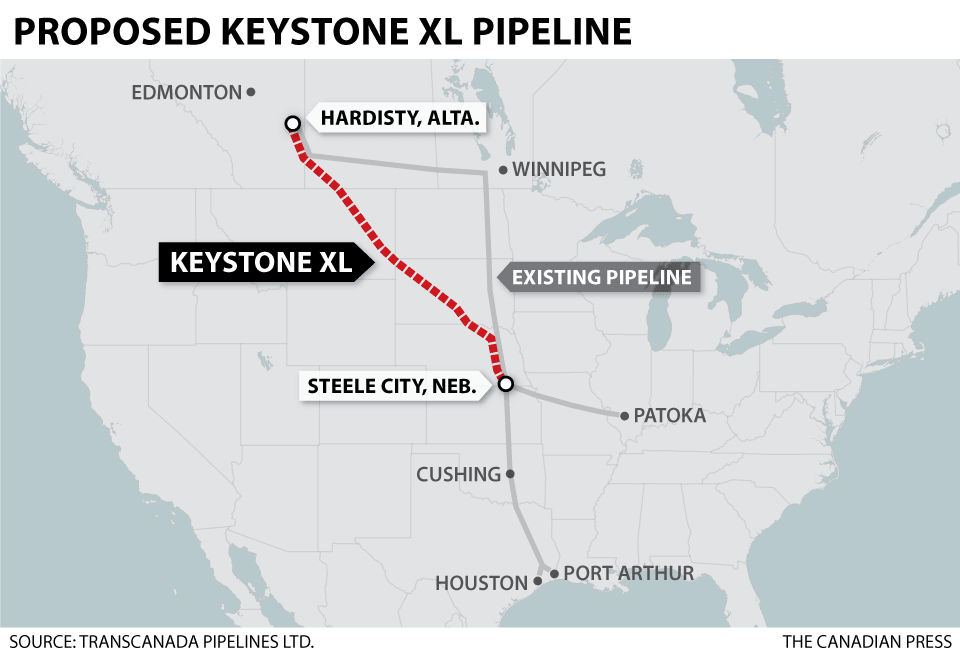

A quick glance at the Map shows you why:

The whole point of Keystone XL is to take Alberta’s extra-heavy oil from the middle of Canada to the U.S. Gulf Coast. And why to the U.S. Gulf Coast? Because you need specialized refineries to process extra-heavy oil, and most of them are on the Gulf Coast.

And why, pray tell, would so many refineries designed to handle extra-heavy oil be concentrated there, of all places? Because that’s the logical place you’d build a refinery to process Venezuelan and (to a lesser extent) Mexican extra-heavy oil!

Keystone XL is, in other words, a naked attempt by Canada to grab Venezuela’s share of the U.S. oil market.

(Aside: in this sense, Keystone XL is, ironically, entirely unlike the other pipeline in the news these days, Dakota Access. That one would bring light crude from North Dakota to the Gulf Coast, but light crude doesn’t compete with Venezuelan crude for refinery capacity, since it uses a whole different set of refineries! In fact, it’s in Venezuela’s interest to have more light crude in the Gulf, as we need that stuff to mix with our extra-heavy crude so it can flow through our own pipelines! In fact, quite a lot of U.S. light crude already does the “round trip” — from the Gulf to the Faja del Orinoco and then back again. More is better!)

But back to Keystone XL. I called Francisco Monaldi, who knows everything worth knowing about the oil industry, to ask him about it. He sounded concerned, but far from panicked.

“First of all, all of this is going to take time. Transcanada,” the Canadian company that would build Keystone XL, “has said they want to reapply for the project, but that only opens up a complicated negotiation with the Trump Administration, which has said, for instance, that they’ll insist U.S. steel is used for the project.”

There are, it turns out, a lot of uncertainties, and the pipeline wouldn’t be ready before the 2020s.

“The pipeline always wins,” Monaldi says, “it’s a matter of reliability of supply.”

Assuming it does get built, though, it definitely spells trouble for Venezuela’s energy strategy. Refineries on the Gulf Coast typically work on long-term supply contracts; they don’t buy oil on the spot market. And when the time comes to sign a long-term contract, it’s hard for oil delivered in ships to compete with pipeline oil.

“The pipeline always wins,” Monaldi says, “it’s a matter of reliability of supply.”

Once a pipeline is in place you can be sure oil will flow through it in a way you can’t be sure with ships, which can get delayed for any number of reasons, from hurricanes to their deadbeat owners being too broke to get the hulls cleaned.

Venezuela, of course, has an ace up its sleeve in this whole debate: Citgo. We own some of the refineries on the Gulf Coast. Nelson Martínez can just pick up a phone in Caracas, call Houston and order Citgo to take Venezuelan oil…or, well, it can as long as Citgo remains under Venezuelan ownership.

Rut-row…

Keystone XL, in other words, substantially boosts the strategic significance of Citgo to Venezuela…and we just went and mortgaged the thing, putting it up as colateral on a series of loans we may or may not be able to pay! Fannnntastic!

“Look,” Monaldi tells me, “for a very long time Venezuela’s enjoyed a huge advantage having all these refineries on the gulf set up to process specifically its oil. The problem with Keystone XL is that if you lose that, there just aren’t that many other places where extra heavy oil could be processed.”

Back when oil prices were higher, maybe the math would have worked to build new refineries to process our oil. But if, as has so often been speculated, oil faces a new price plateau not too much higher than where it is now, there’s just no way you can afford the huge capital costs of new refining capacity just to process Faja oil.

For Monaldi, it’s simple: we need continued access to refineries already installed in the Gulf. Even if you keep Citgo, Keystone XL will depress prices for heavy oil on the Gulf Coast, just because there’ll be a lot more of it. But without Citgo, you’re stuck.

Which means Keystone XL turns Citgo —49% of which has now been pawned off to Rex Tillerson’s best friend in Moscow— has gone from “nice to have” to “have to have”.

Gulp.

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 22 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate