Meth Finance

We thought we’d plumbed the depths of awful government financing deals. But BCV's deal with Goldman Sachs is a new, appalling low.

The Wall Street Journal’s Kejal Vyas and Anatoly Kurmanaev report that Venezuela’s Central Bank struck a financing deal so bad last week it makes PDVSA’s swap and Fintech’s repo look harmless by comparison.

The government raised $865 million cash by selling $2.8 billion in previously untapped PDVSA bonds held by the Central Bank. The central bank got just 31 cents on the dollar for the bonds from Goldman Sachs’s asset management arm.

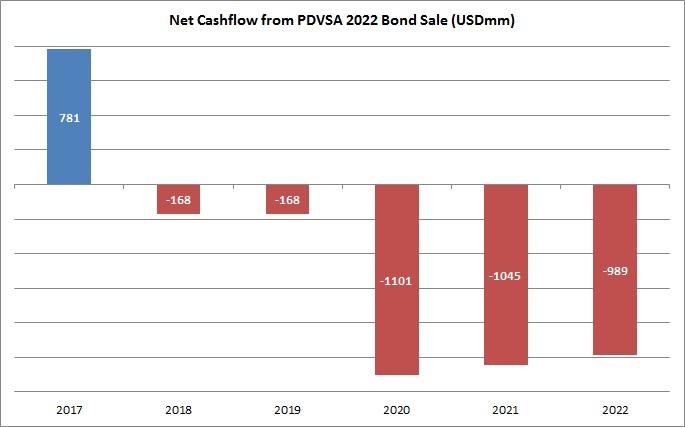

This is atrocious for Venezuela’s public finances. Just look at the deal’s cash flow:

Let’s be explicit about what the graph means: in return for $865 million now, the government committed to dishing out a total of $3.65 billion through 2022, split between $2.8 billion in principal and $756 million in interest. It’s unbelievable. The government now has to fork up the $865 million three times over by 2022 to make good on the $2.8 billion in bonds —and has to pay a crippling $756 million interest on top of that.

It’s like ripping out the electric wiring from the walls of your own house to sell the copper and get your next crystal meth fix.

The deal has an “internal rate of return” of 48%. That means this is equivalent to taking out a loan at 48% interest… in dollars!

This.

Is. not.

Normal!

It’s like ripping out the electric wiring from the walls of your own house to sell the copper and get your next crystal meth fix. Borrowing in these conditions is the kind of self-destructive behavior you might expect from a desperate addict.

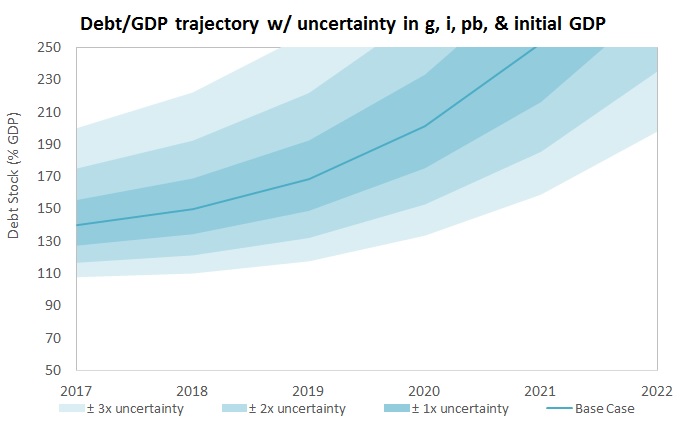

To see how unhinged this is, look at what happens when you put in 48% interest as the price of new financing in a debt dynamics simulator:

The debt/GDP ratio balloons. It blows up. And it’s obvious why: when countries borrow at very high interest rates, they’re forced to take out yet more loans to pay the interest on the old loans and debts pile up exponentially, until something breaks… That’s why borrowing at high interest rates is self-defeating. It only worsens the debt problem and impoverishes the country.

This deal is morally bankrupt: finance as collective punishment.

Oil prices haven’t recovered, PDVSA is broke and Maduro’s government is desperate for cash. They need to win a phony election scheduled for the end of July and there are $4 billion in debt payments coming due in October and November. The regime is out of good financing options and even bad financing options, so it’s now choosing between criminally irresponsible alternatives. But it’s not the only one at fault.

Goldman Sachs and its clients played an appalling role here. They knew they were financing Maduro’s criminal regime. They knew Maduro would use the money to buy phony elections, fund a broken economic system or stave default for a few months in the most unsustainable way. They knew their money wasn’t going to finance infrastructure, development or anything remotely benign.

Their deal is morally bankrupt: it’s finance as collective punishment.

Per WSJ’s reporting, Goldman wagers that “a change in government could more than double the value of the debt.” I wouldn’t be so sure: PDVSA’s 6% 2022 bonds were issued and sold to the Central Bank in dubious conditions in 2014. Venezuelans only found out about their existence months later in PDVSA’s debt report. And their sale last week for 31 cents on the dollar was, if not illegal, then egregious and immoral.

Every reasonable economist I’ve talked to agrees that the next government should call a moratorium on debt payments, get international financial assistance and use the funds to raise imports from $17.8 billion to something like $35 billion. That’s the best shot we have of transitioning to market economy, putting the accelerator and growth and wages, and making sure people feel the improvement quickly. From the point of view of economic policy, that much is clear.

But given the PDVSA swap, the Fintech Repo, this 48% debt issue and what’s to come, it may also be politically expedient to pursue a hostile debt restructuring or even repudiate some the debt to free up money for imports and score points at home.

Venezuelans already have good reason to distrust Wall Street. Everyone agrees that most of the money from debt and oil was squandered. Venezuelans know there’s nothing to show for the trillion plus dollars that poured in: no hospitals, no schools, no roads, no food, no future. And Venezuelans connect the dots. They know that the more money they use to repay these causeless debts, the less there’s left over for imports, production, jobs and a decent future.

Consider this: what happens when a new president is in the driver’s seat of a national unity government and blaming Chavismo for everything goes out of fashion? The political class might need new enemies and scapegoats.

Isn’t Wall Street a natural and deserving one?

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 22 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate