More than a family: a children’s hospital

I went to J.M. de los Ríos Children's hospital expecting to find sadness and dysfunction. What I found is amazing solidarity between people facing one of life's worst ordeals.

“How is your mom?,” the fiftysomething NGO volunteer asks to the lift operator. We’re on the one elevator that still works in this whole section of the building: it’s hot and crowded, but still, the tone is so friendly.

“She’s getting better,” the lift operator replies, like they’re old friends.

The friendliness is a little disorienting. Minutes earlier, the hospital had seemed so hostile. Journalists and even some NGOs are plainly not welcome inside the hospital, and the entrance to the place is designed to intimidate. At the door, an old lady in a beige Milicia Bolivariana uniform stands guard behind a rusty old desk. She take a discerning look at people who don’t seem familiar and keeps a huge accounting notebook open to a blank page, while National Guardsmen loiter behind her.

Built in 1937, the JM de los Ríos Children’s Hospital is not just old, it’s filthy. The walls look like they were meant to be white, but have long since gone an off-putting grey; the tiles on the floor look several shades darker than they were meant to be. It’s noisy, too: moms with babies in their arms, other kids running around — the place is abuzz at all hours.

When the dingy old elevator disgorges us onto an upper floor, you feel like you’ve stumbled on a big family gathering. Everyone seems to know one another. Moms and nurses ask each other about their loved ones. Where I was seeing dirt and misery, the people around me seem to see a home and a cozy new family.

“We didn’t know each other before this, now we’re like sisters”, a young mom told me while I visited the room where she stay had been staying for a month with her baby.

The room was small, with old blue ceramic tiles covering the walls, the air conditioner was not working, neither the sink. The three babies there slept quietly while their mothers had a chat.

The three moms look under 30.

“When you live what we lived in this room you become more than family”, the first one told me as she puts all her belongings in a small black suitcase. She’s small, wearing blue leggings and a white shirt. Her son was discharged the day before but her family in Maracaibo, her hometown, was still collecting money for the 12 hours bus ride home.

“When you live what we lived in this room you become more than family.”

She took the opportunity to ask for some help to buy a corset that her son needs after an operation for an infection. “I’m supposed to change his diaper every three hours, to prevent a new infection but I can´t. You know how much one diaper costs? I change his diaper three times a day, it’s what I can afford”, she confesses with her heavy maracucho accent.

Meanwhile another mom was standing in silence in the room. She told me her son has been in and out of the hospital after his first birthday. Now three years old, he’s fighting a cancer she would be able to treat, if proper chemotherapy drugs were available.

“When I started to come to the hospital you only had to buy rubbing alcohol but now they don’t have anything, there are no painkillers or antibiotics,” she said. The worry disappears from her face when she approaches the baby’s bed. “¿Qué pasó gordo? Say hi,” she said, before explaining to me he’d lost the ability to focus his eyes due to one of the tumors in his brain.

“To get the medicine that he is taking all my family ask for money and then they visit every pharmacy in the city,” she told me.

The “beds” for the moms are some red and blue mats that they fold up during the day. Between the heat at night and the babies crying, the moms barely sleep at night. A set of Mickey Mouse bedsheets cover the only window and some of the moms spend the day fanning their babies with sheets of paper.

“You become family, here,” the maracucha explained. “For example she is from Táchira, so she doesn’t have your real family close to here.”

The tachirense mom is looking at her baby. Fair skinned and lank she’s wearing a red tracksuit. She starts to tell me her story, in a way that suggests she’s told it a million times before.

“My baby was premature and when the doctors took him out of my belly they broke some vessels in his brain. He had a hemorrhage and now he’s dealing with hydrocephalus” — buildups of liquid in his brain, basically.

“In Táchira,” she continues, “they don’t have the equipment to operate him, so we had to came to Caracas (…) the doctors put a valve that drains the liquid from his brain.” She seems tired.

“Right now, the medicine that he is taking comes from Colombia, but it’s hard to find”, she tells me. “And expensive,” the maracucha yells from the other corner of the tiny room.

In the corridor there’s a small celebration, a nurse has managed to open a room that a NGO it’s going to use to keep all the donations. The key had gone missing so the lady used an old X-Ray sheet to pry open the door. Now the NGO staff, all ladies with white hair and carrying huge black bags full of donations, were going inside. The small room was supposed to be for the kids, but now it’s full of broken down medical equipment.

In the next room over there are three more babies, all struggling with hydrocephalus.

“You have to make friends in here, not only because of the situation and the time you spend here, but because it makes it all easier,” a mom told me. Minutes earlier, another mom explained to her where to get antibiotic for her baby.

The key had gone missing so the lady used an old X-Ray sheet to pry open the door.

A little further, two moms share tips about another NGO that helps families from other states during their visit to Caracas.

“There are a lot of kids from other states: Zulia, Mérida, Bolívar, they’re coming all the time”, a nurse told me.

“It’s not easy to come here for the first time. I was alone with my baby. I came by bus from Zulia and it was only my second time in Caracas,” a young mom wearing crocs next to her baby sleeping.

“I have a cousin here, but she’s married with two kids so she’s pretty busy all the time (…) When I first came to the hospital I was lost, but in a few days you become friends with the other moms and you learn how to look for medication, how to find the doctors, how to wash the babies, how to treat the nurses, how to get food, the hours to use the bathroom, where the cheaper labs around to get blood tests are.”

None of it is easy. You have to struggle to look for antibiotics, and each dose can cost Bs.90,000 —two weeks’ minimum salary— if you can find it. The moms sleep in terrible conditions, they struggle every day to get the hospital to provide “decent food” for the babies. Yet they still find time to talk about the latest gossip shows playing on a small TV inside one of the rooms. You can hear the laughter after “El Gordo y la Flaca” dished on the love life of some famous latina actress.

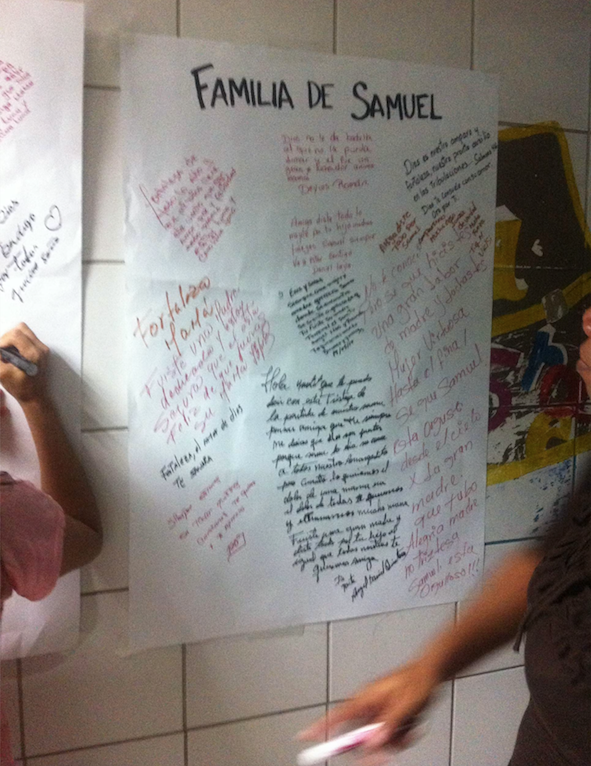

On the corridor, close to the elevator, they have put up two posterboards up and a line of moms queuing up in front of them. But they’re not in line for some scarce drug, they’re waiting to write a message to the families of Samuel and Raziel, two of the kids that died two days ago after they picked up a hospital bug in the kidney unit.

“They didn’t disinfect the dialysis machine properly, so 15 kids got sick,” a mom in a brown tank-top and flip-flops tells me. “My boy it’s one of them. He’s taking two antibiotics out of the three that he needs. There’s a country-wide shortage of the most important one, and the other two are donations so there is no way to ensure how many more he will get.”

She knows that, without the proper drugs, there is only so much the doctors can do. Right now, she’s focused on the message that she is going to write for Samuel and Raziel’s moms.

She knows that, without the proper drugs, there is only so much the doctors can do. Right now, she’s focused on the message that she is going to write for Samuel and Raziel’s moms.

“Have strength, you were a devoted mother (…) I know that, up in heaven, Samuel is proud of the mother he had,” someone writes before going back to her room, back to her struggles.

“Let’s fill the whole card, Samuel and Raziel’s moms are going to feel your hugs when they read this,” the NGO volunteer says.

“It’s true. We’re a family here, even in the tragedy you find light,” the dialysis mom told me as I turned to leave.

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 22 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate