Bring Your Own Popcorn: Watching Movies Amidst Venezuela's Hyperinflation

With fewer places to go and options to spend their money, Venezuelans go to the movies to forget their problems, even though the movie theater industry has seen better days.

Photo: Serious Eats

A week ago, I went to see Coco at my local mall. It was the first time I went to the movies since September, and despite the overall emptiness of the place, with a food court where fast food employees lean on the counter and check their phones, I found a decent crowd lining in front of the theater.

Not everyone went in, though; the fee went up 50% in two weeks, and a hundred times more expensive than when I saw Dunkirk last August. The chilling sound of stukas over the French coast has got nothing on the tension of checking prices among what’s on its way to become the world’s largest hyperinflation ever recorded.

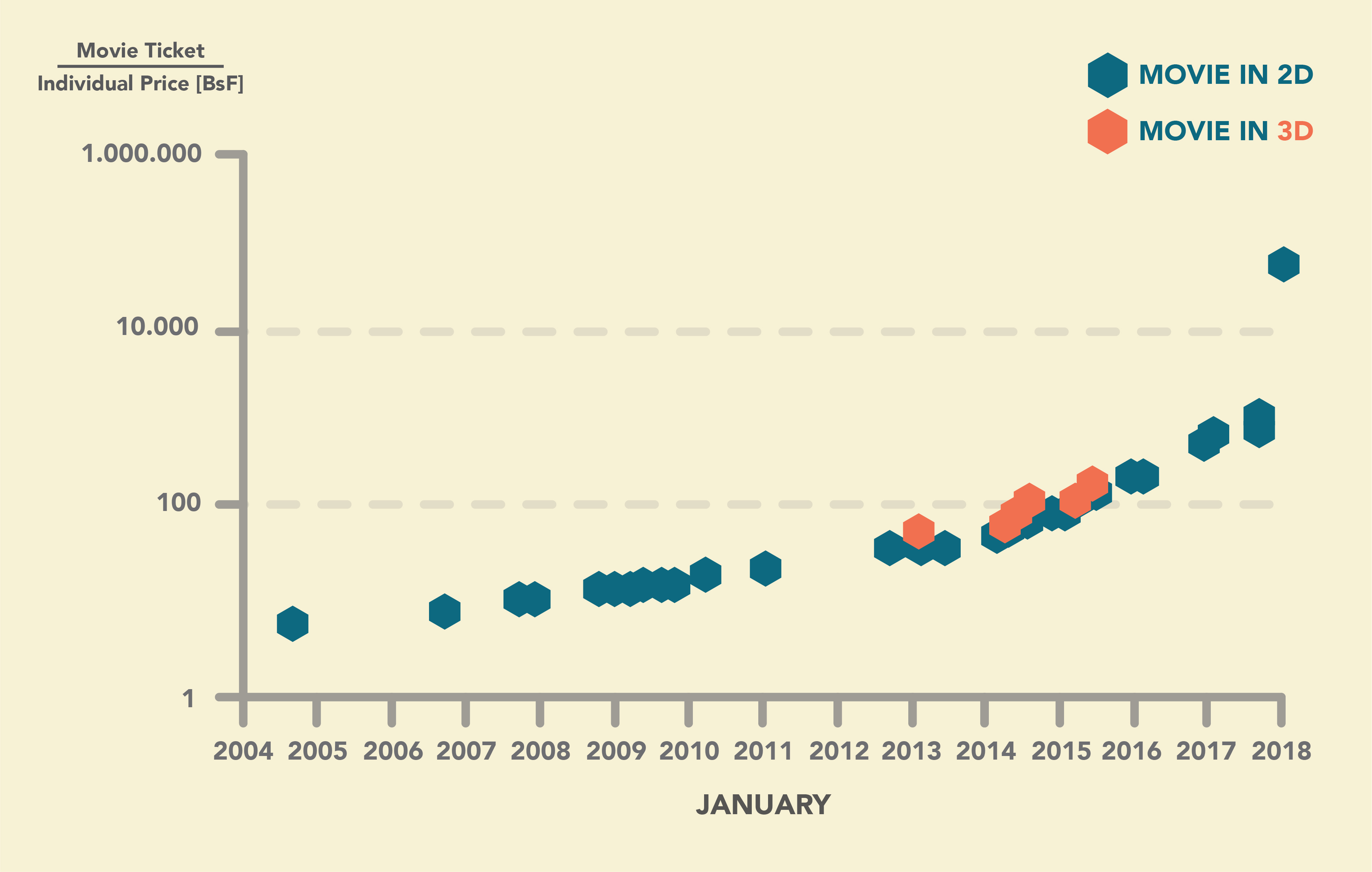

As any self-respecting film buff, I like to collect movie tickets. Going all the way back to 2004, it provides quite a view how of hard have we fallen.

You wouldn’t think this is such a big deal. After all, entertainment is a luxury. But arts are a human need, entertainment is a human need; and not having the space to just tune out in a place like Venezuela is a matter of mental health.

With plazas and streets turning progressively hostile (entire areas of Caracas are ruled by armed groups), the few leisure activities we still have stand as a beacon in this wasteland of the soul.

And a quick look reveals that people still go to the movies despite hyperinflation, blackouts and falling infrastructure. Families, couples and friends, all paying less than half a dollar — and half of that on Mondays! — attend the movies to forget, luckily, what life in Venezuela has become.

Numbers, though, are telling. In 2017, the monthly average of moviegoers was around 1,743,000, a small drop from 1,785,000 in 2016. But between 2015 and 2016, movie attendance fell almost 60%.

To survive, movie theaters rely on sure hits and productions with broad appeal, screened in several rooms for a long time. Less commercial films tend to be limited or never arrive at all.

With plazas and streets turning progressively hostile, the few leisure activities we still have stand as a beacon in this wasteland of the soul.

How these measures hold up on the long run is a matter of speculation, particularly when dealing with international distributors. For instance, recent Oscar winner The Shape of Water wasn’t released in Venezuela because 20th Century Fox gave up dealing with the country last year.

According to José Pisano, CEO of movie distribution company Blancica, it’s easy to see why: “those with rights for Latin America negotiate in dollars. If there’s any agreement, it’s paid in bolivars and the companies see what they do with that currency.”

In other words, they know they won’t get their money back from smaller releases but they can’t allow themselves to leave that room unoccupied. Seeing how the projector bulb costs around $1,500, it seems like it’s just a matter of time before the industry suffers an inevitable collapse.

And it’s not just about the movie, it’s about the experience. People come for the promise of not just watching a movie but of “going to the cinema.” And like a film reel and a clapperboard, another of its symbols is the popcorn.

Most people in that Coco screening with me had the popcorn-and-soda combo the cinema sells, to my surprise, in one size only, even if it costs four times more than the movie ticket, eight times on a Monday.

Those with rights for Latin America negotiate in dollars. If there’s any agreement, it’s paid in bolivars and the companies see what they do with that currency.

Others were eating corn chips, from a cheap brand which I later noticed people bought from the pharmacy downstairs, around the same price as the movie ticket. In a country where hunger is rampant, there’s something obscene in the gesture of having snacks, it’s both a tradition and trying to recapture a misplaced sense of normalcy.

After all, those of us in the audience are here to enjoy and not think of all the issues affecting one of the few affordable spaces we have left. That’s for faceless entrepreneurs who, despite the effort, probably won’t get the recognition they deserve.

Instead, we’re enthralled within a fantastical world inspired by Latin American culture were families overcome distances by the power of love and memory, and boisterous murderous villains are plainly revealed as frauds to everyone. There are tears and laughter and a catchy tune that lingers with you well after you left.

The movie ends, the lights turned on, the ushers come out with a garbage container and the spell breaks. You check your phone, probably seeing the latest news, and you walk a corridor leading you back to the real world.

You were in a dark room with dozens of strangers, mesmerized, feeling another life not only seems possible, but real, even for a flicker of a second. The make-believe filters out the scarcity and the lines and the devastation, but who knows for how long those illusions will last, leaving only our everyday nightmare to remain.

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 22 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate