How FAES Can Destroy Your Whole World

Desiré Cumare, a nurse from Maracao, at the southwestern tip of Caracas, saw how the regime’s death squad killed his son kicking his head, “just because we can”. They also sacked the apartment. “It’s a war on us.”

Photos: Ulises Zavala

“After screaming my heart out, I asked them ‘Why did you kill my son?’”

“‘Because I have the power to do it,’ they said.”

Desiré never saw their faces. They took over her street, went through the apartments, kicked down doors, shouted orders. It was the first raid she’d ever witnessed. “I screamed and screamed and my neighbors didn’t come. They couldn’t. Everyone was stuck in the same nightmare.”

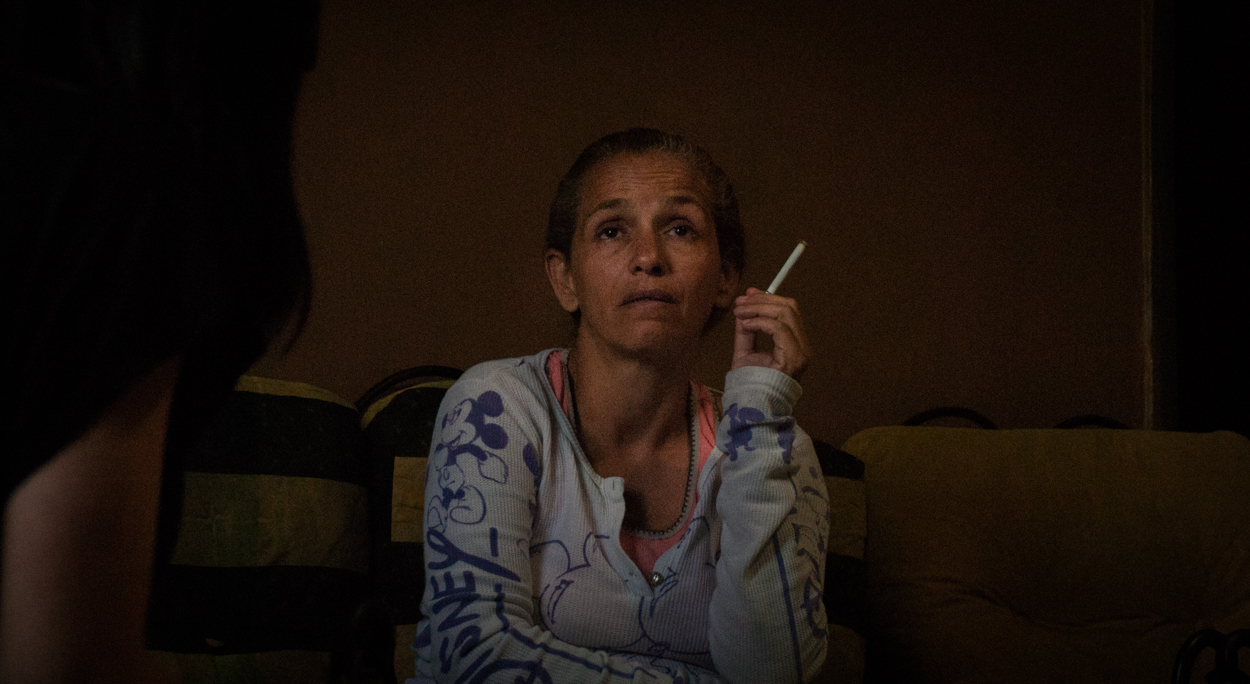

Desiré Cumare, Maikel’s mother, hides after her son’s execution and FAES’ threats.

Desiré Cumare, Maikel’s mother, hides after her son’s execution and FAES’ threats.

She moved to Macarao with her son six years ago, after losing her house in a flood. “This isn’t an area where criminals live. My neighbors work hard, very hard, just to put food on the table and pay the bills.”

“Macarao, for me, is a middle-class area,” says El Catire*, an ex-con from Petare. “That’s why it’s easier for security forces to get in, murder at will.”

Maikel Jesús Cumare Ávila was 21 years old when he was murdered by FAES officers in front of his mother, Desiré Cúmare, last January 8. At 9:00 a.m., Desiré heard a knock on the door. In a flash, masked men had a gun to her face.

Police, open up.

“I screamed and screamed and my neighbors didn’t come. They couldn’t. Everyone was stuck in the same nightmare.”

“I screamed and screamed and my neighbors didn’t come. They couldn’t. Everyone was stuck in the same nightmare.”

“I couldn’t. I started shaking. They threatened to shoot me if I didn’t open the metal door. Maikel took the keys and opened himself. They burst in, pushed him to the ground and started kicking his head against the floor. That’s how they killed him. They cracked his skull.”

Desiré jumped on the FAES officers, tried to make them stop, take off their masks, to make them explain what was going on. They hit her and forced her out. She saw at least 50 officers in the area, and then she heard the gunshot from inside her home.

Maikel Cumare’s room after January 8.

Maikel Cumare’s room after January 8.

Desiré is a 41-year-old nurse. “I was mother and father to him. I spent my life working for him. Now I have nothing left, no family, no home. It’s all gone.”

Scorched earth

Maikel was born on January 20, 1997, in Los Teques Hospital. Even when he was too small to talk, he could sing. “He was an artist. Talented, creative, funny, caring. He didn’t finish high school because he wanted to devote his life to art and music. He was never disciplined or tidy, but he had a good heart. I couldn’t walk for three years, and he took good care of me, cooked me delicious food. He volunteered at a community radio station. Maikel was my only company in life.”

Cristina*, a close friend of the family, remembers him as a playful glutton, full of witty remarks peppered with a shameless humour. Yirken*, a coworker, describes him as “a true brother to party with. We met while he worked at Radio Macarao, he started helping us and ended up producing events. He worked hard, but he also knew how to have fun. His murder was a mistake, they mistook him for someone else. Or maybe he helped the wrong person once. I can only guess.”

Maikel produced and hosted parties and volunteered at Macarao’s community radio.

Maikel produced and hosted parties and volunteered at Macarao’s community radio.

This was the first reported massacre of the year. Between January 8 and 9, FAES swept Macarao from Kennedy to Santa Cruz in an operation that resulted in eight casualties and many arrests. FAES was born in 2017, by Maduro’s direct order, with the purpose of fighting crime, but they’re currently known as the bolivarian police death squads, leading repression against protesters.

The question remains: What are FAES’ objectives when it comes to ground operations? Victims’ testimonies insistently highlight their violent MO: intimidation, break-ins and executions. Anyone who’s ever had an experience with FAES, describes them as an extermination group.

“FAES keep saying that they only murder criminals, that they only neutralize armed people. But Maikel died of a broken skull. How could they have beat him if he was armed?”

“FAES keep saying that they only murder criminals, that they only neutralize armed people. But Maikel died of a broken skull. How could they have beat him if he was armed?”

While I interviewed Desiré at her hiding spot—which is spine-chillingly similar to where El Junquito Massacre took place, one of FAES bloodiest operations to date—Maduro spoke from the National Guard Headquarters in Macarao, a couple of blocks away from her home: “The bolivarian revolution is the sole responsible for the expansion of force we see today, to protect the country from kidnapping, extorsion, drug traffick and terrorism.”

Not even the pipes left

Deep inside the Misión Vivienda complex, the normality of everyday life has melted with strange rumors of security forces.

Deep inside the Misión Vivienda complex, the normality of everyday life has melted with strange rumors of security forces.

Desiré and Maikel lived in one of the 50 towers of a Misión Vivienda complex. Deep inside, the normality of everyday life has melted with strange rumors of security forces. Some neighbors claim to have spotted drones over the towers at night. Others say someone hides inside the complex, and the raids are aimed at that person.

A broken door welcomes us; then, a broken window: it’s a gunshot, clearly the biggest wound amidst these walls. Maikel’s room still has the bloodied mattress, the tainted sheets, and his torn shirt. The neighbor who lets me in sighs and whispers a little prayer for the fallen. “Thank God I wasn’t home that night. I wouldn’t be standing here, showing you this sad, sad place.”

Maikel was shot after being beaten, and while some neighbours claim they saw the officers get him to his knees, they also remember the fear and confusion that defined the situation.

Maikel was shot after being beaten, and while some neighbours claim they saw the officers get him to his knees, they also remember the fear and confusion that defined the situation.

Desiré and Maikel’s home reeks of their past life. The same officers that murdered the boy looted the place. “They took our food, our clothes, our TV, some light bulbs. Our ID cards. They even took the pipework from the toilet.”

“After killing Maikel, they took out his body. Threw it in a truck, like a dog. They detained me until 4:00 p.m., the female officers mocked me and beat me. Then they left me in the middle of the street in Las Adjuntas. I was lost. They told me to go to the morgue and to watch my back, because they’d come back to kill me and the rest of my family. I walked back home and the officers were still in my house when I arrived. They were taking everything they could.”

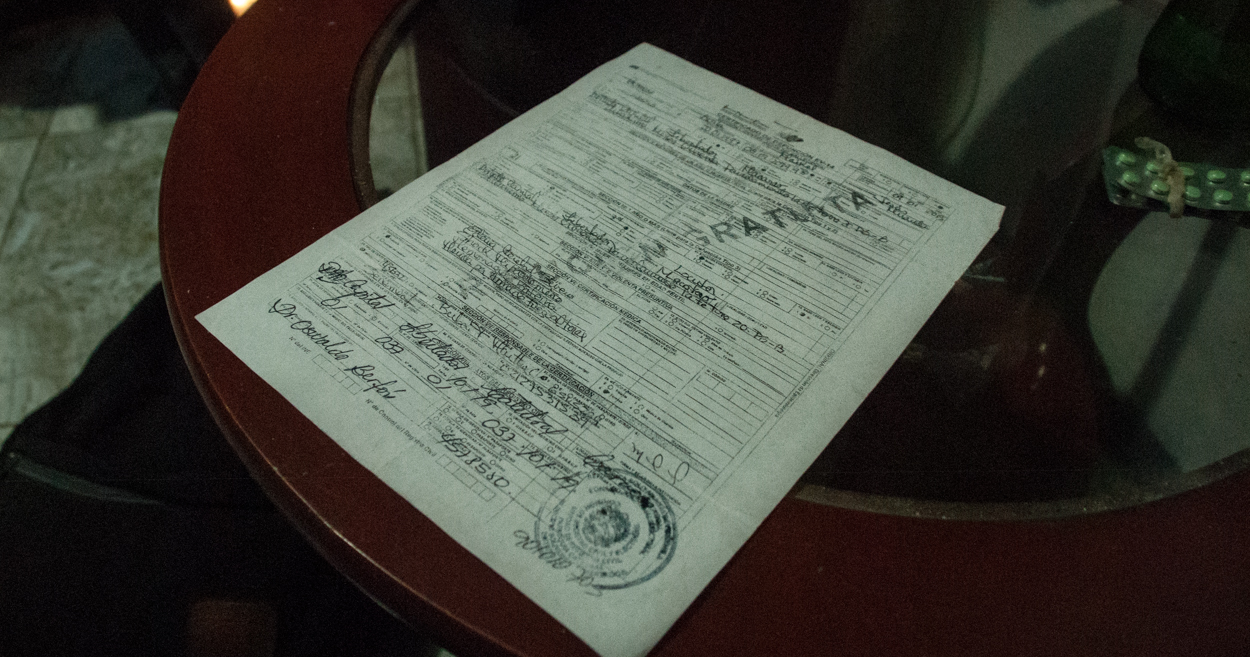

The same day, CICPC detectives showed up, half upset at FAES’ blatant abuse of civil rights, half bored at how normal this has become. At the morgue, Desiré found herself with 18 other grieving mothers who lost their sons that same night at the hands of FAES. “The government has declared war on us. They kill us with hunger, with worry and then they kill your family in front of you.”

“Thank God I wasn’t home that night. I wouldn’t be standing here, showing you this sad, sad place.”

“Thank God I wasn’t home that night. I wouldn’t be standing here, showing you this sad, sad place.”

Macarao doesn’t feel like the home of a massacre. Still, what Desiré describes as a quiet, prosperous, barrio is currently under a self-imposed curfew, like many others across the city. Children still play, “but only for half an hour.” Lovers still walk the streets, “but never when it’s dark”.

Since then, Macarao displays a wound. Birds fly above the GNB trucks that constantly transit the area, walkers sit to enjoy the dusk, but those who talk of FAES don’t dare speak the name. A neighbor, who asks repeatedly to remain anonymous, says: “Many have sent their children and teenagers someplace else. They have seen what they can do. They know it can happen to anyone.”

“I’ve heard people speaking of what will happen next. In six months, FAES won’t exist anymore. But something will take its place, something harder for all of us.”

“I’ve heard people speaking of what will happen next. In six months, FAES won’t exist anymore. But something will take its place, something harder for all of us.”

We wait for the bus and speak of the future and this strange hope that has survived through whispers of war. “I’ve heard people speaking of what will happen next. In six months, FAES won’t exist anymore. But something will take its place, something harder for all of us. That’s how it’s always been.”

Leaving Macarao, a stranger in the bus describes the barrio’s many areas. “I was born and raised here. I love my home and it looks like I’ll die here, too. In a way, it makes me happy, but now I fear an ugly death.”

*Some names and identifying details have been changed to protect the privacy and indentity of individuals.

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 22 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate