Learning Barrio Politics at the Burning of Judas

On Easter, Venezuelan barrios and villages choose a prominent political figure, build a doll, and burn it to mark the end of the Holy Week. The press usually covers it because the custom registers who the population is blaming for its problems. This year, Guaidó had his baptism of fire, along with Maduro and Trump.

Photos: Cristian Hernández

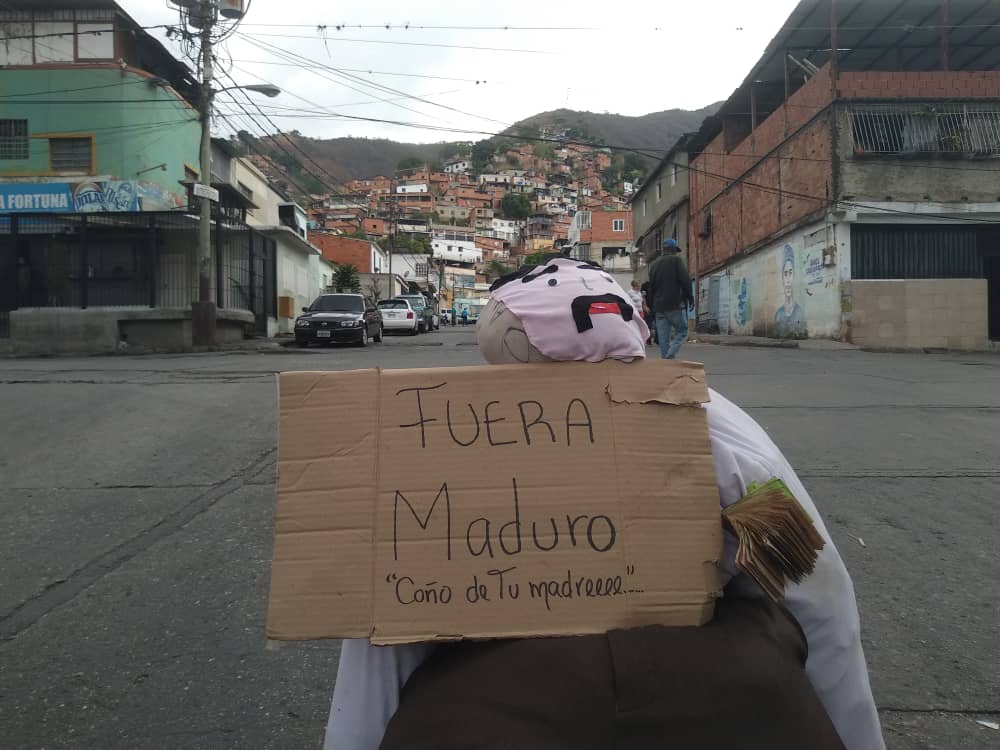

“Last year, we were attacked by colectivos because we were burning Maduro,” says Romel Martínez, Acción Democrática activist and community leader of El Cementerio, a barrio known for its hawkers and black market. “This year, we wanted to avoid violence and fear, we wanted to speak to everyone and find joy despite our differences, so we decided to make an apolitical Judas.”

This year the organizers from El Cementerio decided to make an apolitical burning of Judas, nevertheless, the celebration was not apolitical as many cheered in favour of their political leaders.

This year the organizers from El Cementerio decided to make an apolitical burning of Judas, nevertheless, the celebration was not apolitical as many cheered in favour of their political leaders.

Their Judas represented the blackout and the generalized lack of services that have struck the country, affecting barrios in Caracas more than any other areas. The event itself was not apolitical, though: Juventudes PSUV cheered and sang in favor of Maduro, while other neighbors gathered to scream in favor of Guaidó and against the growing poverty. “We’ll probably never root for the same politicians, but you should stay and see them at 2:00 a.m., when they start to hug each other and laugh at the mean stuff they say to each other.”

The youngest danced changa and shared cocuy shots with neighbors and visitors alike.

“Last year, we were attacked by colectivos because we were burning Maduro,” says Romel Martínez, Acción Democrática activist and community leader of El Cementerio.

“Last year, we were attacked by colectivos because we were burning Maduro,” says Romel Martínez, Acción Democrática activist and community leader of El Cementerio.

It’s a ritual of catharsis wrapped in a religious celebration: the burning of Judas—Jesus’ traitor and one of Christianity’s most fundamental villains—is not about who sold Christ for a bunch of silver coins, but a symbolic lynching of some public enemy, generally the leader to blame for the country’s predicaments.

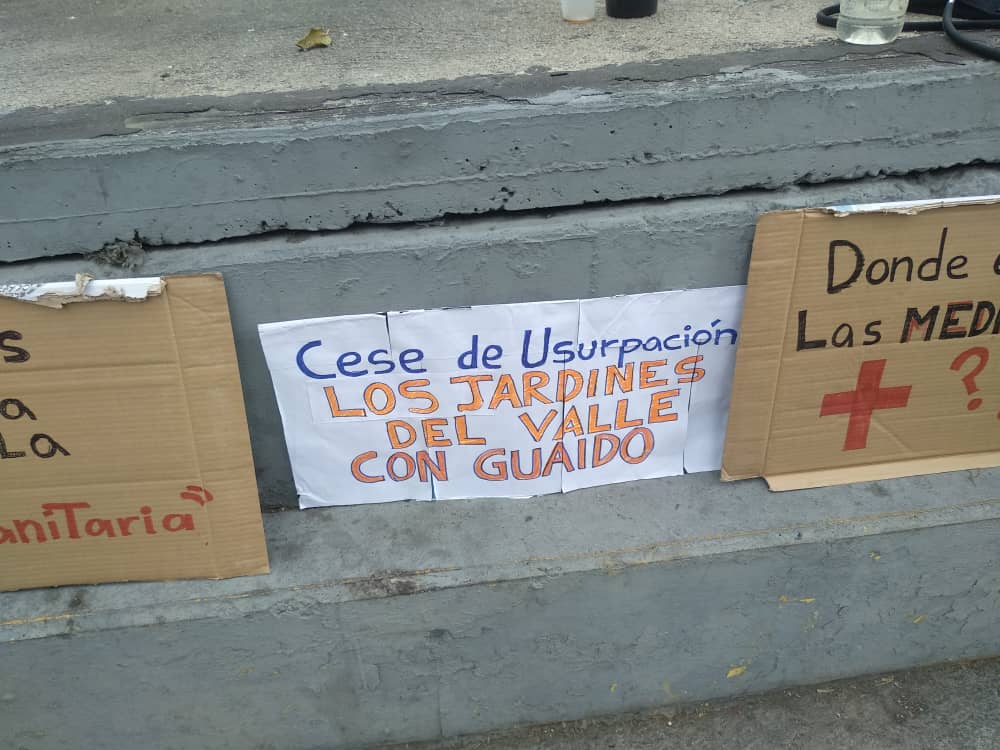

In Intercomunal del Valle Ave., neighbors set up the burning of Judas as a protest for the lack of medicine and lack of control and proper distribution of the humanitarian aid.

In Intercomunal del Valle Ave., neighbors set up the burning of Judas as a protest for the lack of medicine and lack of control and proper distribution of the humanitarian aid.

By settling a score, this display of popular justice, this celebration of vengeance from the people to their negligent, ill-intentioned leaders, it’s also an event that mirrors the violence behind hope in desperate times.

“This is an important celebration for the community,” says Marlouyan Loaiza. “My family has been organizing the burning of Judas for the past 76 years. My father, and his father before him cared for this community and we have seen this tradition slowly fade away.”

Pedro assures colectivos won’t come to threaten them as long as he’s there. “I have earned their respect. I used to be chavista, there are many like me here today. I used to have a food store, right here on this corner, now I have nothing.”

Pedro assures colectivos won’t come to threaten them as long as he’s there. “I have earned their respect. I used to be chavista, there are many like me here today. I used to have a food store, right here on this corner, now I have nothing.”

In El Valle, residents claim the tradition has been becoming less and less important for the last 40 years. “Barrios are a dangerous place, and El Valle has seen a lot of blood and violence in the past decade,” says Pescao, a 68-year-old resident born and raised deep inside the community. “It’s hard to convince people to enjoy the streets when they’ve lived all their life trying to hide from malandros, colectivos and cops.”

In El Valle, residents claim the tradition has been becoming less and less important for the last 40 years.

In El Valle, residents claim the tradition has been becoming less and less important for the last 40 years.

In Intercomunal del Valle Ave., neighbors set up the burning of Judas as a protest for the lack of medicine and lack of control and proper distribution of the humanitarian aid. “We haven’t gotten a glimpse of the humanitarian aid, but we have all seen bachaqueros sell it in Petare and Catia. This was meant to help us, and instead, it has turned into a new business for criminals,” says Anneliesse Toledo, a lupus patient who has to fight body tremors as she speaks. While we talk, two chavista neighbors start screaming: “We elected Nicolás, he’s our president; you should be burning that clown that wants to take his place without anyone’s support.” Everyone reacts: some tell him to get out, others ask him what are they going to do without medicine, others laugh. Meanwhile, Pedro, from Valencia but raised in El Valle, tells me colectivos won’t come to threaten them as long as he’s there. “I have earned their respect. I used to be chavista, there are many like me here today. I used to have a food store, right here on this corner, now I have nothing.”

“We haven’t gotten a glimpse of the humanitarian aid, but we have all seen bachaqueros sell it in Petare and Catia. This was meant to help us, and instead, it has turned into a new business for criminals,” says Anneliesse Toledo, a lupus patient who has to fight body tremors as she speaks. Photo: Gabriela Mesones Rojo.

“We haven’t gotten a glimpse of the humanitarian aid, but we have all seen bachaqueros sell it in Petare and Catia. This was meant to help us, and instead, it has turned into a new business for criminals,” says Anneliesse Toledo, a lupus patient who has to fight body tremors as she speaks. Photo: Gabriela Mesones Rojo.

“This is a celebration for the community. We all gather, peacefully, to speak our minds. This is a cultural event. These are our traditions.” Photo: Gabriela Mesones Rojo.

“This is a celebration for the community. We all gather, peacefully, to speak our minds. This is a cultural event. These are our traditions.” Photo: Gabriela Mesones Rojo.

In El Paraíso, neighbors gathered around a South Park-style two-headed Maduro in an active protest with anti-Maduro and anti-Cuba banners and cacerolas. “Over 100,000 people live in this area, but people don’t want to protest for their future,” says Carmen, a resident from the area who used to be a nurse but had to quit her job because of how insignificant her salary had become. “They’d rather sit in their homes doing nothing.”

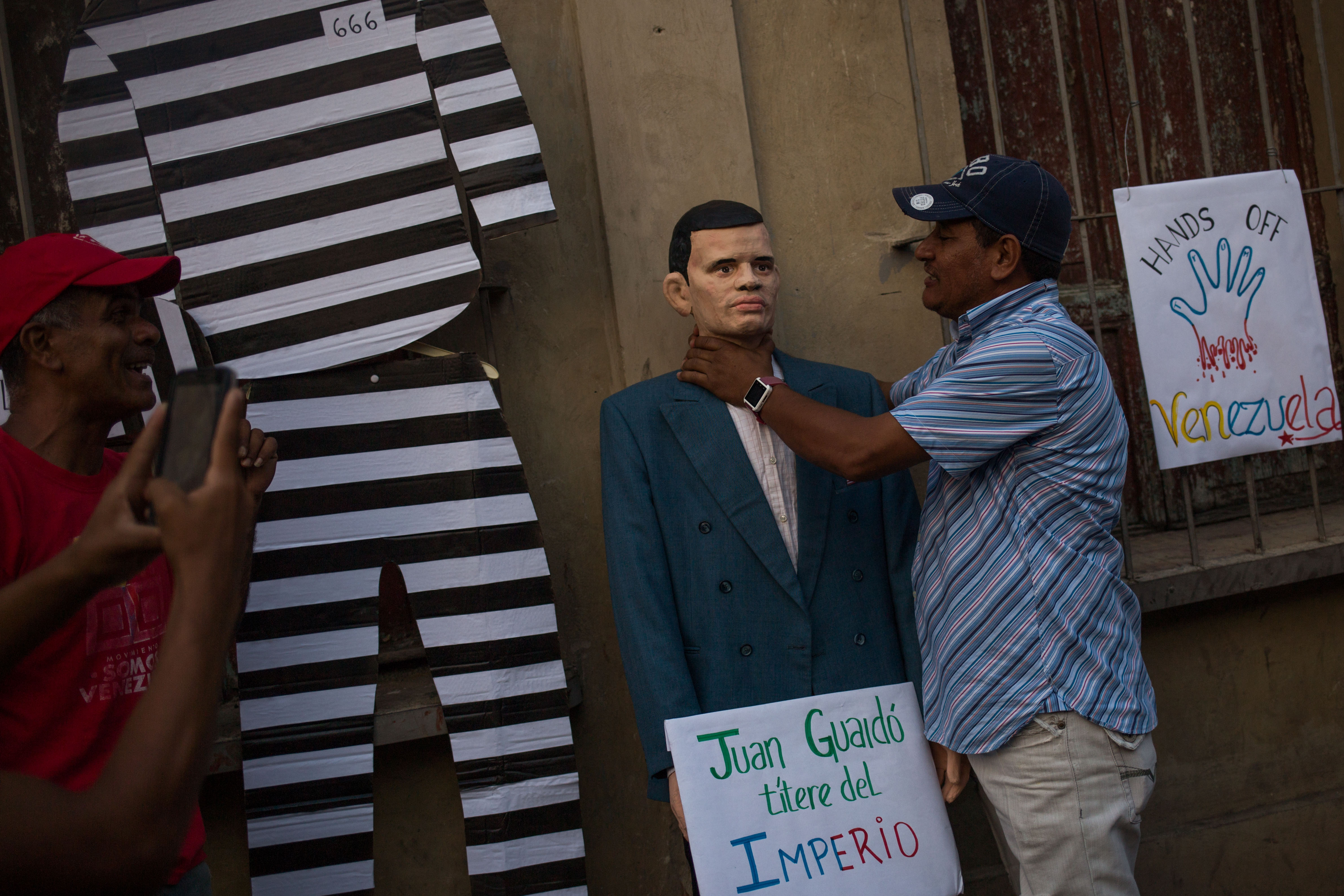

The biggest celebration took place in San Agustín, a barrio known for its strong community values and musical diversity. In 2010, San Agustín was named Musical Heritage of Venezuela. Salsa was the center of the burning of Guaidó, hosted by Grupo Niche, Lluvia Sky and El Abuelo Salsero.

El Abuelo Salsero, one of San Agustín most spirited and respected musicians.

El Abuelo Salsero, one of San Agustín most spirited and respected musicians.

“We’ve been celebrating the burning of Judas for the last 34 years,” says José González, the main organizer of the event, a timid 30-year-old man with piercing eyes and a PSUV shirt. “I make the dolls, and it takes me more than a month to do it. I am interested in making it as realistic as I can. I remember when it was hard for us to make this party, when we were burning presidents it was scarier, more violent. Now it’s all about having fun and not worrying about a thing.”

San Agustín has one of the oldest burning of Judas tradition, as they have celebrated it for the last 34 years.

San Agustín has one of the oldest burning of Judas tradition, as they have celebrated it for the last 34 years.

The doll is filled with small fireworks, so it explodes as it burns. Children run and women hide, while men throw more fireworks into the fire.

The doll is filled with small fireworks, so it explodes as it burns. Children run and women hide, while men throw more fireworks into the fire.

Kids played sports and ran around hitting each other while grownups danced under the sun. Unlike the burning of El Cementerio and 23 de Enero, this was a straight-edge, abstinent, salsa celebration.

“Guaidó pretends to give the country to the empire. We won’t allow it. We are proud, we are strong. We celebrate life by killing the traitors of this land.”

“Guaidó pretends to give the country to the empire. We won’t allow it. We are proud, we are strong. We celebrate life by killing the traitors of this land.”

When it was time to burn Guaidó, women gathered to insult the “self-proclaimed clown”: taconero, lambucio, perdedor, traidor, asesino, incapaz. The doll is filled with small fireworks, so it explodes as it burns. Children run and women hide, while men throw more fireworks into the fire. A couple of shots are fired into the air and the party goes on until dawn. Ro, one of the dancers and hostesses, chases kids with a mischievous laugh: “Guaidó pretends to give the country to the empire. We won’t allow it. We are proud, we are strong. We celebrate life by killing the traitors of this land.”

The streets of the 23 de Enero are empty while colectivos from La Piedrita burn a giant doll of Trump sodomizing Guaidó. “They are traitors of national peace and humanity, they deserve to burn,”

The streets of the 23 de Enero are empty while colectivos from La Piedrita burn a giant doll of Trump sodomizing Guaidó. “They are traitors of national peace and humanity, they deserve to burn,”

Sexually explicit Guaidó and Trumps dolls are a common sight, most of them referencing homosexuality as an insult to these political leaders.

Sexually explicit Guaidó and Trumps dolls are a common sight, most of them referencing homosexuality as an insult to these political leaders.

On the other side of the city, the streets of the 23 de Enero are empty while colectivos from La Piedrita burn a giant doll of Trump sodomizing Guaidó. “They are traitors of national peace and humanity, they deserve to burn,” says one of them, with a cheerful smile on his face and a bottle of rum in his hands, which he has no problem to share. A couple of blocks away, a samba group cheers the streets while Catia residents display their Judas, unrecognizable for everyone present.

“It’s a hungry person, like us,” one of them states. “Come back at six! Let’s all burn hunger together!”

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 22 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate