How Brutal Are Venezuelan Police Forces?

The Monitor for Lethal Force in Latin America published its first report, covering Brazil, Colombia, El Salvador, Mexico and Venezuela. When it comes to executions, we’ve earned more medals than in the PanAm Games in Lima.

Photo:800 Noticias retrieved

This piece was first published in Spanish in Cinco8.

What’s the Monitor del Uso de la Fuerza Letal en América Latina?

It’s a working group based in Mexico, focused on gathering academics on security and human rights, to document and spread information about how many people are dying at hands of the police and armed forces in the region (one of Latin America’s biggest human rights issues—it’s not just in the U.S.). The researchers behind the report come from countries involved in the study; from Venezuela we have Keymer Ávila, who works at the Institute for Penal Sciences from the Universidad Central de Venezuela. This first report clearly states the nature of the problem, also looking into the international legislation, getting precise on how their indicators are laid out, and it ends with several suggestions on how to reduce these embarrassing numbers.

Why should we even care?

Because of the same reasons it’s important in the U.S., Canada or anywhere else. The thing is, Venezuelans can be ambivalent here: For example, in social media, many cheer for the killing of perceived criminals, taking this perception at face value (the murders are usually at the hands of the police itself).

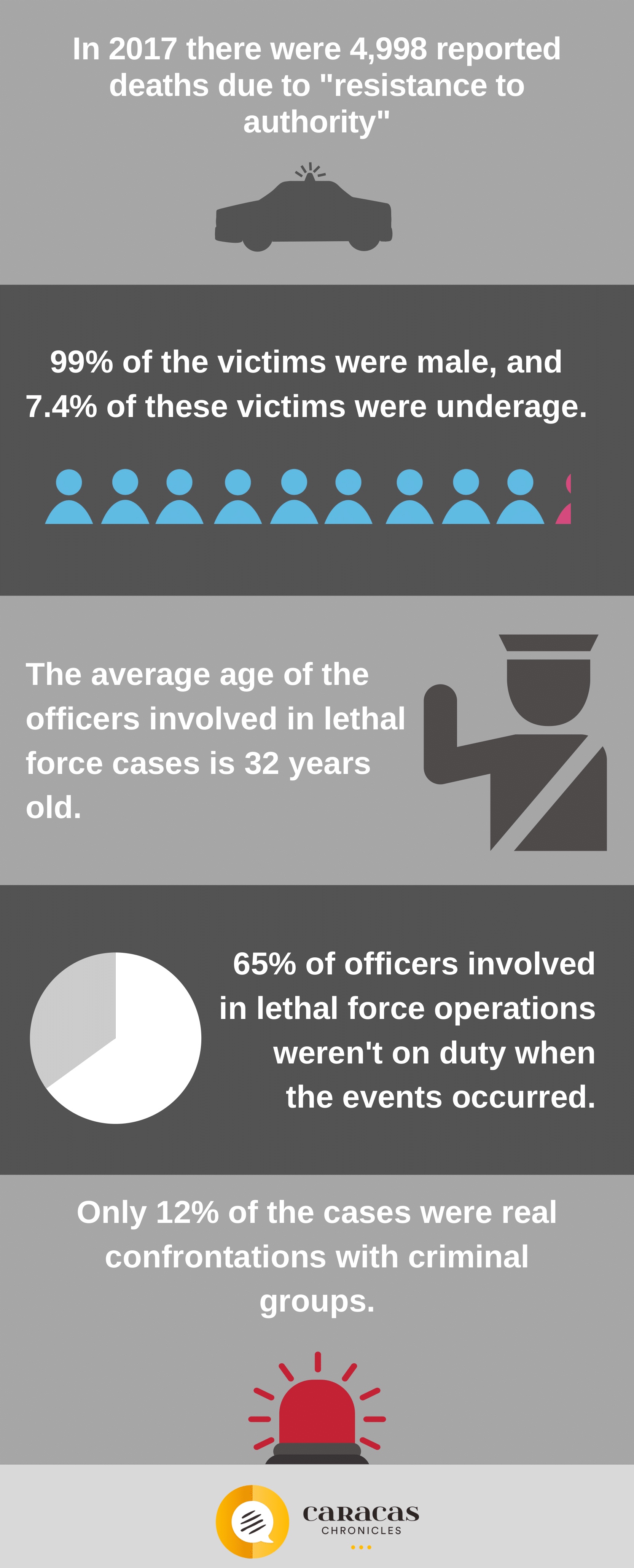

Because the world isn’t black or white, the subject is hard to study and judge. Some laws state that a police officer or army member has a right to end another person’s life, given certain circumstances; they’re the ones supposed to monopolize violence, after all. But officers often go too far. This continent has had a long tradition of dictatorships and crime rates that seem permanently on the rise, and these excesses represent a very serious matter for two main reasons. First, to unlawfully take a life, even if you’re wearing a uniform and using a regulation firearm, means that the law is being sabotaged and the access to basic rights is truncated. Second, when officers kill, they often kill innocent people, planting evidence to make it look appropriate. They do kill felons, just as executions—not shootouts. This is why this report refers to victims as “civilians,” that’s what they are whether criminals or otherwise. This distinction is not always clear, and even if the subjects were guilty, we don’t carry the death penalty. These are extrajudicial executions.

How bad is the situation for Venezuela?

According to the report (with figures from 2017) it’s dire.

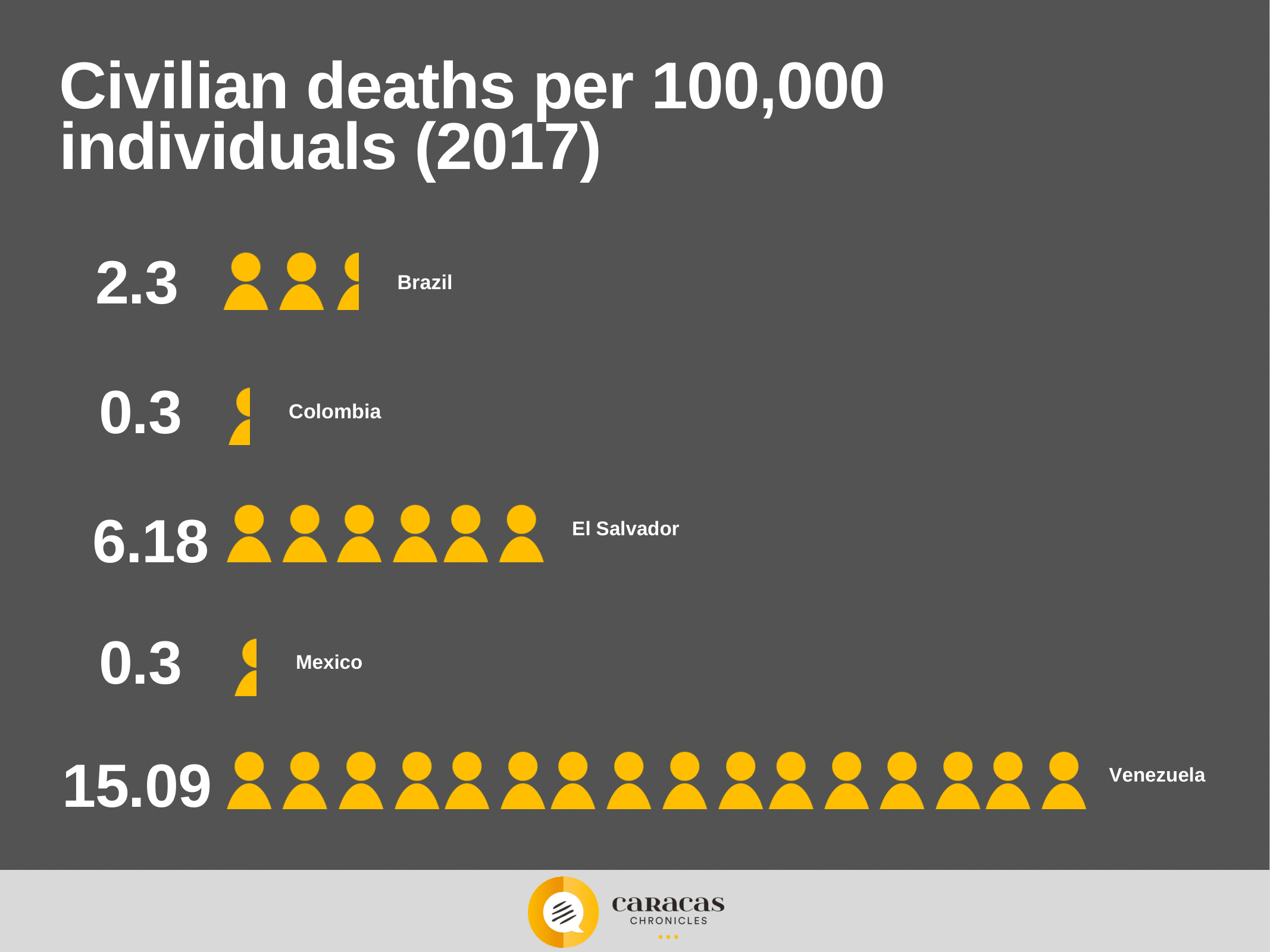

These numbers predate the action plans carried out by FAES (the Special Action Forces of the National Bolivarian Police) although they come after the exponential increase —caused by the Operaciones de Liberación del Pueblo (People’s Liberation Operations)—of killings by law enforcement agents: In 2010, this rate was of 2.3 per 100,000 individuals, while in 2016 the number rose to 19 per 100,000 individuals, according to the Justice Ministry. That’s a 726% increase.

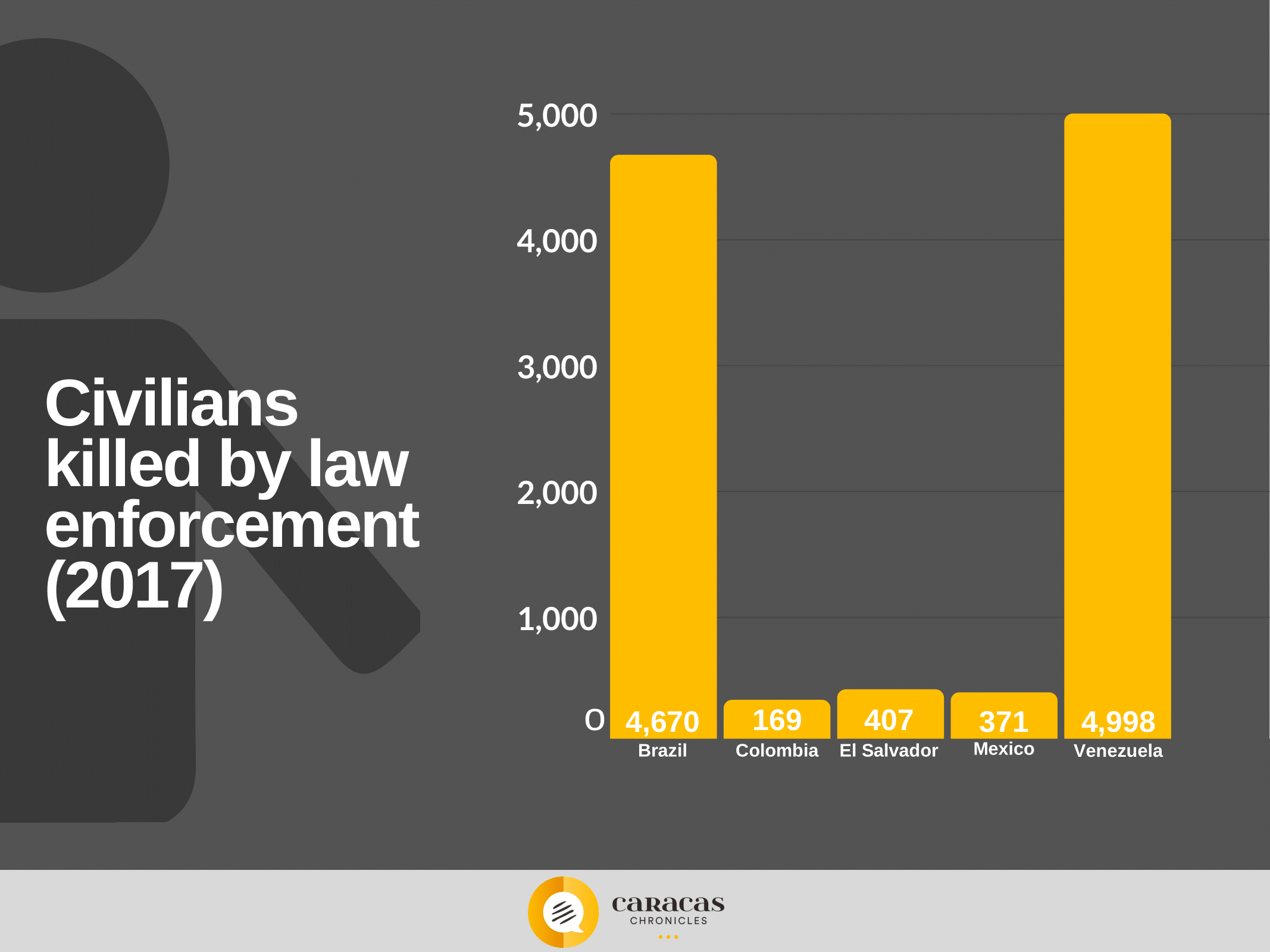

The 2017 numbers say that there have been more civilian deaths at the hands of law enforcement agents in Venezuela than there are in Brazil, which has a population seven times greater. This means that over a quarter of homicides committed in Venezuela are carried out by the state.

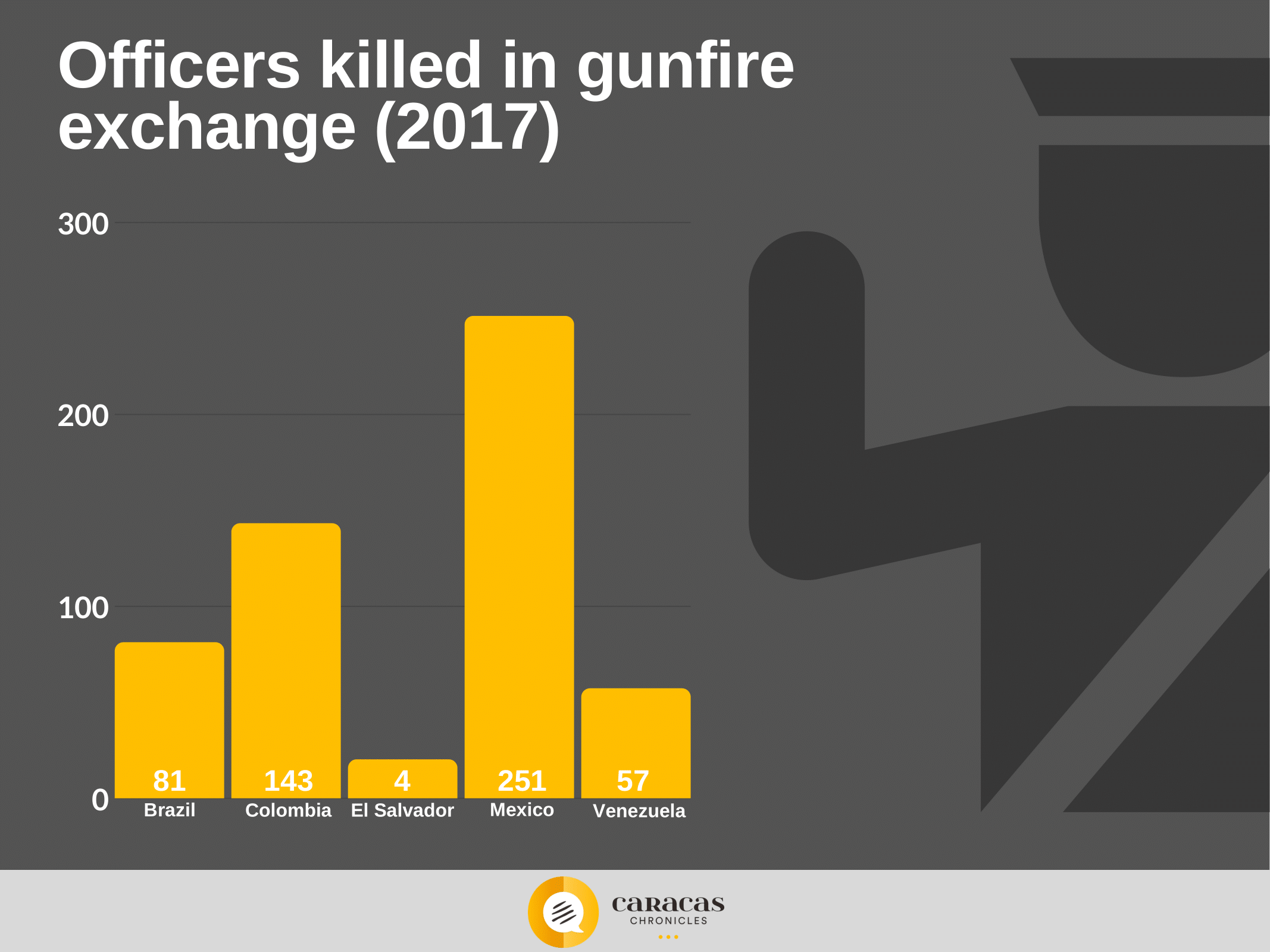

This has many layers. The Monitor program warns that the lethality of police and armed forces increases the risk of violence towards themselves. This is why, in Venezuela, there’s a noxious cycle: Criminals kill police officers and national guards, who respond in kind. The more killings from one group, more retaliations.

The research in Venezuela was led by Keymer Ávila, who points out that security in the country has been militarized for eight decades, with a violent logic in which criminals (and, in good measure, the poor) are seen as enemies. Officers don’t adhere to the legal limitations of a democracy, but to a criteria that relies on exceptions and the open violence of war. His analysis, which should be read entirely, is based on data such as:

Where does the information that the Monitor handles come from?

The sources are official numbers or, particularly for Mexico and Venezuela, authorities and press reports, both independent and pro-regime. Ávila has a victim registry, complete with full names to avoid double counts, and they are compared to records taken by human rights NGOs like Provea and Monitor de Víctimas.

In Venezuela, just as health and disease rates aren’t properly published, homicide figures aren’t reported clearly: Law enforcement usually writes reports as if describing an armed conflict, naming those executed as casualties. Sometimes they miscount the number of murder victims, when they weren’t killed by the police or if they passed away after being wounded. Counting murder victims is a very difficult task and the number are easily manipulated by governments, especially dictatorships. That’s why independent reports such as the one published by Monitor del Uso de la Fuerza Letal en América Latina are so important, however flawed in the original data (as explained in the report’s methodology section).

To quote the research team: “The information obtained with this study allows us to reach two relevant conclusions. The first one is the lack of transparency when addressing the use of lethal force in Latin America and, as such, the need for important data to be published and released regularly, so that specific monitoring may be possible. The existing obscurity in several countries made it impossible to calculate and study different indicators. The second conclusion is that the numbers point to an excessive use of force in various countries in the region, placing Venezuela in the most dramatic position, followed by El Salvador. All of the analyzed nations, with the exception of Colombia, exceed the accepted limits in at least one of the points considered in the abuse of force. It is urgent, therefore, that both the governments and society look for a way to change this scenario.”

We know what Maduro’s regime thinks and does about the problem. The questions that remain unanswered are: How would this be handled in an eventual transition towards democracy? And how convinced is Venezuelan society that killing criminals (or innocent people presented as such by law enforcement agents) isn’t the way to a safe and peaceful nation?

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 22 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate