How Spain Turned Venezuela into a Political Throwing Knife

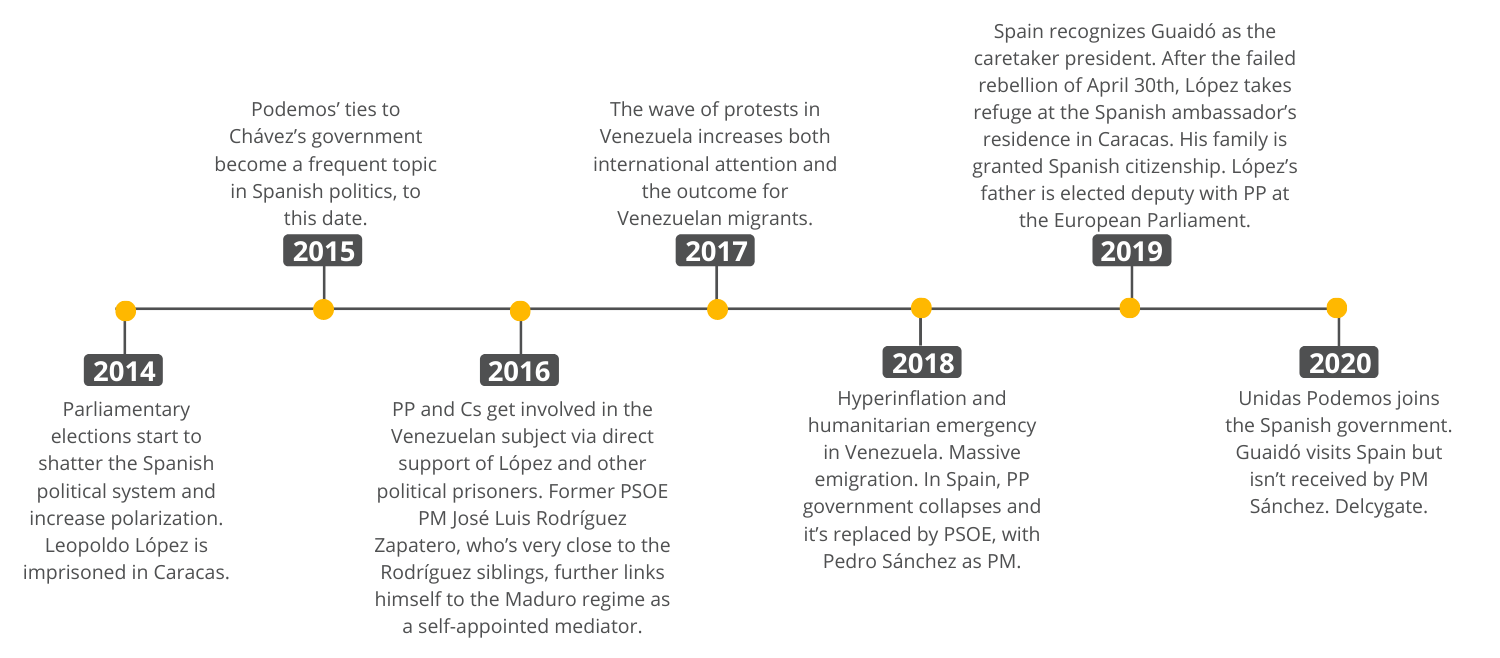

If you think Venezuela became a frequent subject in American politics, see how populism and corruption has made us a staple in the polarized Spanish scene since 2014, with some effects in our country

A weapon of choice, for all sides.

Photo: Reuters

In the past six years, I’ve heard the name “Venezuela” spoken in some of the most disconcerting ways yet since leaving for Spain in the late 2000s. Politicians over the world have become adept at brandishing it against one another whenever it best suits them and as often as context would allow it (and abusing it when not). Our country seems to have landed itself an awkward, yet vital role as a famously handy throwing knife. And this rhetorical weapon flies across by the dozens as a very divisive socio-political moment, the 2020 U.S. elections, begins its run to boot.

How does a knife-wielding party like this start in the first place? Look to Spain for an answer.

A Shift in the Political Landscape

Besides the fact that many people from Spain emigrated to Venezuela in the 1940s and 1950s, and that there are close cultural and familial ties between the two countries, Venezuela was thrust into Spain’s current political scene as it reached what felt like a watershed moment in its still short democratic installment. The modern Spanish democracy started with dictator Franco’s death in 1975, and it’s still dealing with ancient wounds of the 1930s’ Civil War.

Since 1982, the country has settled into a bipartisan constitutional monarchy alternating governments under the Spanish Socialist Workers’ Party (Partido Socialista Obrero Español, PSOE) and the People’s Party (Partido Popular, PP), echoing the sides of the conflict. Century-old social democrat party PSOE was instrumental to Spain’s democratic transition, whereas Catholic conservative PP was George W. Bush’s and Tony Blair’s closest ally in Iraq. Between the two, they have produced three and two prime ministers respectively, with their tenures spanning 38 years. And it was two such administrations, namely those of PSOE’s José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero (2004-2011) and PP’s Mariano Rajoy (2011-2018), that brought about the circumstances for a major turning point in the political landscape.

Zapatero’s non-response to the 2008 financial crisis had fatal consequences for the economy and later offered justification for gruesome austerity in Rajoy’s first term. The public also learned about decades of corruption in both parties during Rajoy’s tenure, springing a protest movement out of a demonstration on May 15th, 2011. Come 2014, this had set the young-yet-tried bipartisan system to go belly up.

To top it all off, in February 2015, they received a not-so-veiled endorsement from our very own Diosdado Cabello.

That year, on the eve of a large batch of elections, two additional parties came onto the scene as newer, cleaner faces for either side of Congress. One was a center-right Catalonian regional formation aiming to go national, and the other surged in the left, as an offshoot of the Indignados protest movement, born in the evictions and layoffs massified by the economic crisis. The former called itself Ciudadanos (Cs) and presented itself as the true center option, while the latter, Podemos, sported a brand of left-leaning populism with which our expat community was all too familiar.

The December 20th, 2015 general election produced the most diverse Congress in Spanish democracy since the 1980s. The parliament was so fragmented that a snap election had to be called in 2016.

And it’s here that Venezuela’s current role was defined for Spanish politicians and their constituencies. After Podemos had early successes in the 2014 European elections and in the 2015 local elections (winning Barcelona’s town hall on May 24th), all sorts of verified and alleged ties were revealed between three key figures in its leadership and chavismo. To this day, general secretary Pablo Iglesias features a video on YouTube of a segment he did for Venezuelan state TV in 2013 praising Chávez’s life and work; in an interview for state media that year, party coordinator Íñigo Errejón celebrated the lines that had begun forming at stores in an obscure interpretation of Venezuelan society. And co-founder Juan Carlos Monedero came under fire in January 2015 for having failed to report money earned for consulting services offered to the Chávez regime over a five-year period.

To top it all off, in February 2015, they received a not-so-veiled endorsement from our very own Diosdado Cabello.

The Friends of Leopoldo López

In January 2016, a newly minted, opposition-led National Assembly in Venezuela set up a commission to look into the chavista regime’s alleged funding of Podemos. They also engaged representatives from all other major Spanish contenders—PSOE, PP and Cs—and these involved themselves to varying degrees.

While PSOE’s general secretary Pedro Sánchez walked an ambiguous line between sympathy and indolence, PP’s leadership—to which Leopoldo López’s wife and father made appeals—was in a position to offer support from elected office at both national and regional levels. Central government speeded the delivery of citizenship to López’s relatives throughout the year, and the Madrid regional administration provided its seat to hold an event on March 15th, 2016, for the promotion of López’s book Preso pero libre. And yet no involvement was as vocal and visible as that of Cs general secretary Albert Rivera, who the AN invited over for a congress on democracy and human rights.

Rivera had reason to accept; even though they shared similar positions on systematic corruption and Cs had started higher up on the polls, the 2015 election saw Podemos become the third force in congress by forming a coalition now known as Unidas Podemos (UP) with like-minded, smaller outfits, while Cs sat fourth.

And yet no involvement was as vocal and visible as that of Cs general secretary Albert Rivera.

So barely a week after Zapatero embedded himself in the Venezuelan crisis as a self-appointed mediator, and despite Diosdado’s threat that port authorities would turn Rivera away at the gates, he boarded his flight on May 24th, met Lilian Tintori at Maiquetía, kept his appointment at the National Assembly (a jab at UP included) and sat with the families of other political prisoners. He was unable to meet with Leopoldo or Antonio Ledezma themselves, but still, it was the most thorough immersion of any running candidate in the subject.

It didn’t prove as productive upon his return though; when a right-wing pundit asked him in an interview whether Venezuela was a dictatorship or not, Rivera favorably compared a dictatorship’s imposed order to the arbitrariness of the Maduro regime.

Iglesias grabbed that during a one-on-one debate, gave it a little spin, and accused him of preferring dictatorship over democracy, saying how clear it was that some benefitted electorally from talking about Venezuela. Agitated, Rivera hoped to surprise his sparring partner with the news that Venezuelan legislators wanted to subpoena him over the money Maduro had given him, but the move didn’t pay off as he hoped.

Discussing Venezuela While Looking Like Italy

Spain’s Congress of Deputies has remained fractured. In this way, 2016 marked the beginning of an “italianization” of Spain’s politics, meaning that its government lacks a clear majority and depends on occasional and frail party alliances.

Accordingly, a crisis within PSOE enabled Rajoy’s second term to get underway on the fourth try, only for Pedro Sánchez to pursue a no-confidence motion in summer 2018, the first-ever to succeed in Spanish democracy. Sánchez took office as prime minister on June 2nd, formed a minority government, and had to call another snap election before his first year was through.

It was this short-lived administration that saw Juan Guaidó become caretaker president, which gave Sánchez a chance to finally compromise on the subject of Venezuela by acknowledging his mandate.

That didn’t last, either. Today, and after years of animosity on the left, a PSOE-UP coalition favored by Zapatero voted Sánchez prime minister by the narrowest of simple majorities on January 7th, 2020, and knife-throwing is all the more frequent now. In closing ranks with Iglesias, now one of his VPs, Sánchez has nuanced his acknowledgement of Guaidó and now refers to him as “leader of the opposition,” whenever he can’t just avoid the subject. He even stood him up during his tour stop in Spain on January 26th, having the Minister of Foreign Affairs meet him instead.

Sánchez has also escaped involvement in the backlash of another encounter, on January 20th, between his Minister of Transport and Delcy Rodríguez at Madrid-Barajas Airport. The Spanish press has dubbed this “Delcygate,” and a legal investigation was launched into the Minister’s conduct based on the unknown purpose of the meeting. While Sánchez has washed his hands of it, PP and right-leaning party Vox have made sure it remains a front-page issue.

As for Cs and UP, they have both fared differently than anticipated. Following Cs’ worst-ever electoral results, Rivera stepped down and has retired from politics, leaving his party in a rut it has yet to overcome. Conversely, multiple investigations have mined Iglesias’s formation in spite of their gains. Spain’s Court of Auditors is currently studying claims of illegal funding to them by both Maduro and the Iranian government, while a magistrate’s court is looking into services they received in 2019 from a political consulting firm which had previously worked for Maduro and Evo Morales and has employed Juan Carlos Monedero, of all people. Meanwhile, now independent Íñigo Errejón has continued his obscure reasonings as late as 2018, when he defended Maduro by stating that the situation had improved, that people now ate “three meals a day” in Venezuela.

With Vox denouncing that the COVID-19 State of Emergency was meant to ruin the country’s economy (while shouting that “We are not Venezuela!”), and UP facing a dim future if the first regional votes under the coalition government are any indication, we ultimately face the same question in Spain that people ask in the U.S. The tone of the conversation around Venezuela has been set against UP much like it has been set against left-of-center Democrats. In the Spanish case, how are we to keep unbiased awareness, let alone increase it?

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 22 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate