Museums and Galleries Fight (on Their Own) to Stay Alive

In January, Chávez’s “cultural revolution,” which reduced to a monochromatic red a whole palette of administrations and symbols, will turn twenty years old. The damage is extensive, but not all is lost

The siege was part of a deliberate plan

Photo: Museo de Arte Contemporáneo

In June, Carlos Zerpa—renowned Venezuelan artist—thanked the invitation for the “Conceptual Art in Venezuela” exhibit, scheduled for 2021 in the Museo de Bellas Artes de Caracas (MBA). He turned it down, though, not wanting to participate in shows and exhibits by institutions of the Venezuelan State. He said that “the idea for the exhibit is fantastic, what’s wrong is doing it in a museum handled by the chavista government […] find another venue that isn’t handled by the government and I will gladly participate.”

Then, Nelson Garrido, winner of the National Award of Plastic Arts in 1991, after having accepted the invitation, also decided to withdraw. Javier Téllez, another invited artist, didn’t accept either: “Obviously I won’t participate in a show at a museum controlled by a totalitarian regime.” Visual artist Sigfredo Chacón followed suit: “I’m not interested in participating, I was included without my consent.”

Zerpa’s stance shouldn’t have come as a surprise to the show’s organizers: in previous years, he criticized several artists (including a graffiti artist with his same name) that were to represent Venezuela as “accomplices”, since they were sponsored by the state in the Venice Biennial. But Noel Zarins, one of the organizers for the concept art show, answered: “It’s an interesting position. In mine, abandoning spaces has been a mistake, like when the opposition abandoned the elections for the National Assembly” and then clarified that he doesn’t identify with either the regime or the opposition. Mariana Silva, one of the other organizers, specified that the exhibit was a private project “looking to confront the institutional and social hardships and generate spaces for cultural expression.” Zerpa snapped back: “A private initiative that aims to have an exhibit in a Venezuelan museum, immediately becomes an accomplice.”

On the other hand, artist Héctor Fuenmayor stepped out in support of Silva and Zarins, whom he describes as “decent people trying to do the impossible in a cultural wasteland.” He explains that he agreed to participate if his iconoclastic work Delirio sobre el Chimbo Raso—censored in the Alejandro Otero Museum, in 2006—was included in the show, along with the documents that registered the scandal. Curator Isabela Villanueva, on her part, considers that meeting with the authorities is negotiating with chavista censors: “They want to have their cake and eat it too, when clearly they follow the government’s lead.”

This is the newest chapter in a political conflict unleashed on Venezuelan art museums since the arrival of Hugo Chávez and his “cultural revolution” of 2001.

The Landslide

The “demolition” of public cultural institutions, according to Lorena González Inneco, art professor at the Universidad Metropolitana and independent art curator, began in January of 2001 when, during a broadcast of Aló Presidente, Hugo Chávez announced the abrupt dismissal of about thirty directors (among them culture giants Sofía Ímber and Mirla Castellanos) from public institutions associated with the National Culture Council (CONAC), a state-run, yet autonomous, organization created by poet Juan Liscano in 1975.

“The cultural revolution that took place in 2001’s Venezuela wasn’t like Mao’s,” former president of the Museo de Bellas Artes and one of the directors fired that year, María Elena Ramos, explains. “It was more like the one by the Italian thinker [Antonio] Gramsci,” whose vision focused on establishing a new supremacy allegedly based on the ideas of the working class. “Culture was becoming elitist,” Chávez said on his show, making reference to intellectuals and cultural agents, “princes, kings, heirs, families, took over institutions.” It was the first blow against the museum’s autonomy, following the suggestion by Manuel Espinoza, then vice minister of Culture, who said in 2000 that they had to “dismantle the state’s foundations” and “dismantle the principality”.

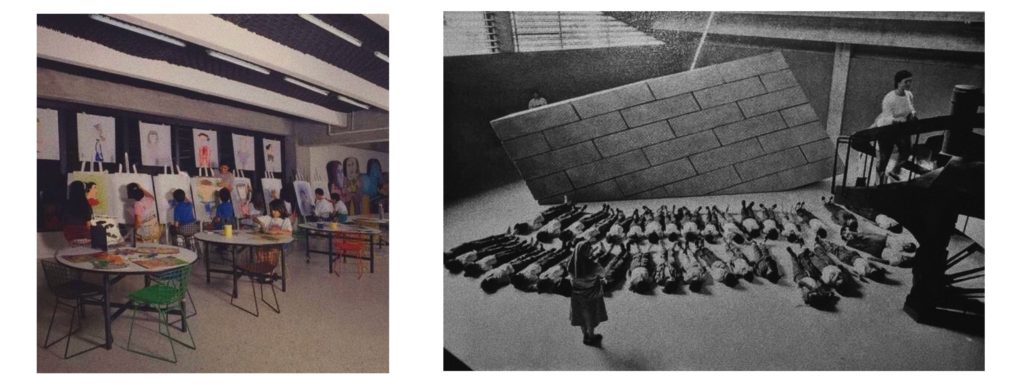

The educational departments of museums took their relationship with schools to heart

The situation worsened when Farruco Sesto was appointed vice minister of Culture. First, by means of veto, he would censor the work of Pedro Morales which was going to represent Venezuela in the Venice Biennial in 2003 and then, using the (discriminatory, illegal list against all opposition-voting citizens) Tascón List, he unleashed an “unconceivable apartheid in our democratic tradition,” Ramos says.

Up until the cultural revolution, Lorena González explains, our museums had had the main collections in the region (from Goya’s Caprichos, and one of the few complete Suite Vollard sets in the world by Picasso, to a Warhol Nixon and a Rodin Thinker), all thanks to three administration models that had begun during the Venezuelan democracy: the museum model (by Miguel Arroyo, in the Museum of Fine Arts, based on museography, department structure, archives, and registry), the educational model (by Manuel Espinoza, from the National Art Gallery, who looked to strengthen the link between the institution and all of its workers, while educating visitors) and the communications model (by Sofía Ímber, from the Contemporary Arts Museum who, as a journalist, spread the museum’s image to all corners of the country). The museums also served as a complement to the education system, where different kinds of professionals could further their knowledge. In fact, it was common practice to welcome interns from all over Latin America, especially Colombia and Argentina, since they “were a bit behind in the museum exercise.”

In 2005, Sesto gave the final blow to the autonomy of these institutions: he abolished the museums’ autonomous foundations (created in 1990 as part of a decentralizing plan), created the Fundación Museos Nacionales (FMN) and even eliminated the logos for each institution, designed by iconic graphic artists from the 20th century, such as Gerd Leufert, Nedo Mion Ferrario, Carlos Cruz Diez, Álvaro Sotillo and Waleska Belisario. Then the CONAC was replaced by the Ministerio del Poder Popular para la Cultura and everything was now linked to the government.

The foundation, recalls González, was “a very bureaucratic place, delaying processes, complicating paperwork, and undermining the economic impulse that the museum could’ve had as administrator of its own assets and profiles. This put an end to the administrative autonomy and the possibility of support by the private sector, condemning museums to weak budgets. For example, González says, the foundation withdrew the name of Sofía Ímber from the Contemporary Art Museum of Caracas and, in 2009, José Manuel Rodríguez, then vice minister of Culture, suggested (unsuccessfully) the return of African, Egyptian, and Chinese art collections of the MBA to their country of origin. The cultural development that Venezuelans lived through, González says, “has been being destroyed, nullified, and forgotten for 20 years.”

The Dissolution of Memory

The FMN would unify each of the museum’s particular collections into one national collection. This way, museums would lose the capacity to approve loans, decide when pieces would return to the storage rooms, or follow the specific conservation manuals for each work of art. Since 1999, the procurement to acquire new pieces has been suspended, according to González, leading to a loss of memory and management.

The Acquisition Committee of the FMN is inactive, says Daniel (a false name; he requested to remain anonymous), an employee of the foundation who explains that they have only bought works of art in clearance sales by the Social Protection Fund of Bank Deposits (Fogade) and the Banco Industrial. This is why making up for time lost in artistic production, González says, would require “a huge institutional and economic effort”: “The cost of abandoning the memory, the testimony, is symbolic, but it is also financial.”

The collection is also in “extremely dire conditions,” González says, because of deterioration in the infrastructure. According to Daniel, the fire extinguishers in museums don’t work, there’s no air conditioning, there’s no safety equipment nor protection or evacuation plans. The water damage in the Contemporary Art Museum’s ceiling has forced the removal of works from the vaults: “fungus grows on the sheets of paper and the paintings begin to bulge out,” Alice (fake name), a museum employee, explains. Moreover, the museums have drawn away from the public and education plans have slowed down, such as the now defunct Maccsibus (a bus from the Museo de Arte Contemporáneo Sofía Imber, which would take exhibits and education courses to schools, remote areas of the country and popular urban areas) or the guided tours and workshops for school groups.

Damage on Marisol Escobar’s “El Avión,” at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Caracas. Picture by Tony Frangie

María de Lourdes Rengifo, director of the GAN (National Art Gallery) between 2015 and 2018 and a former employee of the Alejandro Otero Museum since 1997, says that when you enter the Gallery, you can see it’s already in disrepair. Rengifo, who was known as “the posh girl of the museums”, organized an exhibit celebrating the GAN’s 40th anniversary. In fact, thanks to the ties she had made with the MAO (Alejandro Otero Museum), Rengifo managed to get materials from certain people in the Army (such as a water pump) as well as support from the Fondo de Valores Inmobiliarios, who “practically adopted the GAN” and opened a small exhibit room for photography. Thus, discreetly, many museum administrations have managed to procure some support from the private industry.

But the problems in infrastructure were huge: a utopian GAN Square was never finished, so it is now filled with street vendor stalls and it’s used for militia exercises. There were even talks about turning it into a bus terminal, but “we fought against it, directors against ministers, and it was stopped,” Rengifo says. A president of the FMN approved in 2016 a budget to finish the square and the façade of the GAN but “there wasn’t a bid, they just gave it to a company that put up two benches and that was it.” There are no replacement parts for the original lights that come from Argentina and they have to open the windows to let the natural light in.

So, because of “political demands that I disagree with, I couldn’t take it anymore,” after 23 years, Rengifo retired from the GAN and began to work in the Sala Mendoza, in the private circuit: “I was done. Wonder Woman doesn’t exist.”

The damage to the infrastructure and the centralization of the collections have unleashed rumours of pillage of art pieces in museums, especially after Matisse’s Odalisca de pantalones rojos was stolen from the Contemporary Art Museum (probably taken when it was on loan for an exhibit in Spain), later found by the FBI in 2014, at a Miami Beach hotel.

“That’s just speculation, sensationalism,” González says. Rengifo claims that the GAN has “video surveillance and a committed team” and “in reality we don’t have a lot of art trafficking in this country.” Theft would be “easily detected”, because “everyone knows each other” in the art world. But, things could be different in other public collections that aren’t as controlled, like it was evidenced in the art theft of the Venezuelan Embassy in Washington (Carlos Vecchio, the ambassador designated by the National Assembly, has already started an international investigation).

Stalinism in Caracas

The politicization of museums has prevented exhibits where the work transcends the powers that be, González says. In fact, “there were times when they forced you to put up exhibits of the ministry or gubernatorial management, of Diosdado, of Chávez, with praise to those personalities,” or manipulating history with propagandistic ends. She recalls, among them, “4F February Revolution” (2012) in the Jacobo Borges Museum, the themed exhibit “4-F: From rebellion to utopia” (2012) in the Alejandro Otero Museum and “Comrade Picasso” (2018) in the Contemporary Art Museum.

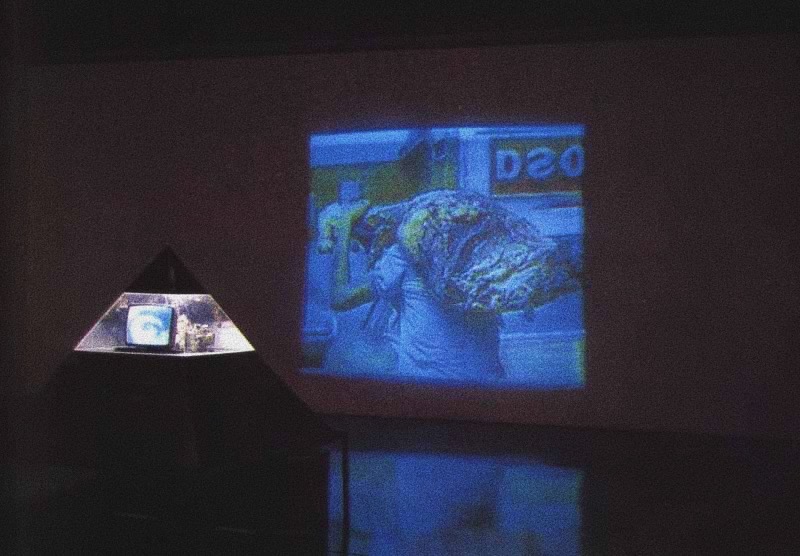

“Management wasn’t unblemished in that regard,” González says, “but you had some range of freedom and the curator was respected.” In 1999, for contrast, the Rómulo Gallegos Center for Latin American Studies (CELARG) showed José Antonio Hernández-Diez’s work In God We Trust, a video-art exhibit which featured images from the Caracazo riots. Luis Pérez-Oramas and Ariel Jiménez organized “La Invención de la continuidad” at the GAN in 1996, which received the visitor with a Soto walk-through kinetic piece that took you to the Meyer Vaisman shack-installation: a critique to the project of modernity of Venezuelan democracy and kinetic art as the official art form.

Back from a time when power could take criticism: José Antonio Hernández-Diez’s “In God We Trust”

The Minister of Culture took over the presidency of the FMN and lots of people lacking the qualifications are appointed in positions where they manage institutions “like a minimarket,” says Daniel. He names Morella Jurado, former director of the Alejandro Otero Museum who “tried to get in line for Minister of Culture” and “was an artist who didn’t graduate.” According to Daniel, Morella Jurado “systematically mistreated” employees and put up politicized exhibits, financed by her friends of the chavista diplomatic corps. Today, the former director has an educational painting show on state-controlled TV station VTV.

Alice recalls a very talked about incident among the MACC (Caracas Museum of Contemporary Art) employees: during a visit by the Minister of Culture, Ernesto Villegas, when they were setting up the “Comrade Picasso” exhibit, a group of employees showed him the Suite Vollard, a series of one hundred engravings by Pablo Picasso which only a few museums in the world, including the MACC, posses in its entirety. After looking at the engravings, Villegas answered: “Okay, but where are the real Picassos?”

Crisis, Exodus, and Resistance

Although several private institutions have done internal inventories, the FMN hasn’t done an exhaustive inventory of the unified collection from 2015, Daniel says. These inspections should be done every year or every two years, or whenever there’s a change in management, according to the law. Besides, since 2015, insurance coverage was lost on most of the artwork, which was international and in dollars.

The loss of budget has resulted in two staff exodus waves. Gabriela Rangel, of the MAO, today runs the Museum of Latin American Art in Buenos Aires; Luis Pérez-Oramas was the curator of Latin American art for several years at the MoMA in New York; José Luis Blondet, of the MBA, is currently the curator for special projects in the Los Angeles County Museum (Lacma), and Julieta González, also from the MBA, is artistic director of the Jumex Museum.

Sofía Ímber with the original MACCSI workers

Yet, resistance against abuse is strong by those still inside. Daniel says “there’s staff working with a commitment that goes beyond conflict,” who are “battling for things to be done right and that have been there for many years in spite of the salaries they get, which aren’t even symbolic.” He says that not all of them have the same political tendencies and the heritage is guarded, although there’s no diffusion or chance for consults. For Rengifo, people should be relieved “because institutions still have valuable people and an institutional commitment.”

The preservation of our collections are in the hands of these people. “If an opening appeared to rebuild and renew these spaces,” González says, “all those who have walked away from museums would join for their recovery, to put together what’s so meaningful to our own history.”

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 22 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate