The Venezuelan Astronomer Who Helped NASA Land on an Asteroid

Behind the successful OSIRIS-REx mission on Bennu is Humberto Campins, one of the leading experts on asteroids

A truly inspiring adventure, as told by an inspiring man.

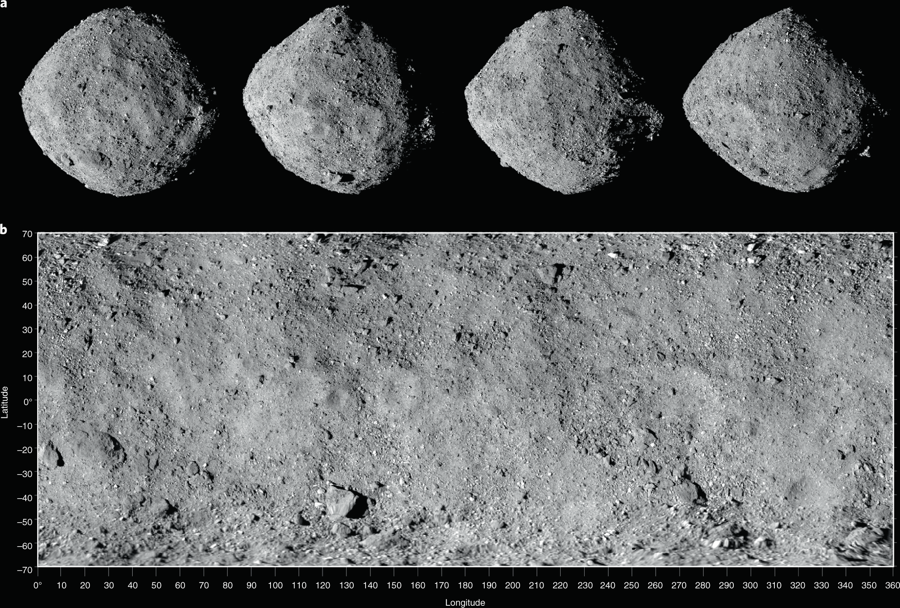

Photo: NASA

On the afternoon of October 20th, a space probe the size of a bus landed on an asteroid in an orbit opposing our planet’s. The area where contact was made isn’t larger than a parking lot and the precision needed to execute this task was inch-perfect. The mission: to collect and recover a sample of Bennu’s soil, a celestial body neighboring Mars and Earth, and on that day, it was travelling over 321 million km away from us. According to the results of the analysis published weeks ago with data sent from the probe, it’s very likely Bennu contains carbon in a way often associated with organic compounds. This means that, on the surface, it doesn’t only carry the primary components which date back to the origins of the Solar System: it may also carry molecular traces of what originated life on Earth.

OSIRIS-REx was launched on September 8th, 2016 from the U.S. Air Force base of Cape Canaveral, in Florida. It reached Bennu on December 3rd of that year and began to orbit the asteroid for the first time by the year’s end. The probe has been programmed to return to Earth on September 24th, 2023, when it must land with a parachute in the Utah desert. One of the specialists who will be there with a pair of binoculars is Venezuelan scientist Humberto Campins, one of the leaders of the expedition.

Dr. Campins, with the upbeat temperament and eloquence that characterizes scholars used to dealing with students on a regular basis, rarely says no to an interview. He usually answers them while eating breakfast or during a short walk. The morning after the mission, we had a scheduled meeting to talk about the OSIRIS-REx, a call that was only possible because of the satellite phone he used to contact me, since the CANTV connection had died in all of Mérida State, where I live, as it usually goes. When the call finally came through, the first thing I noticed was a slight barquisimetano lilt in spite of his 47 years living in the United States. I asked him how he felt after the mission and, between laughs, he said he was very happy with the results:

“I feel a great satisfaction, mainly because the entire team worked very hard for many years and we achieved the main goal, which was to take the samples. I was invited to be part of the team way back in January 2010; so I’ve been working on this for over ten years. It was in 2011 when NASA gave us the funds to build the ship. Since it launched, we’ve been mapping the asteroid and we were finally able to collect the samples.”

Humberto Campins was born in Venezuela in 1954, and studied at Santo Tomás de Villanueva school in Caracas, in the early ‘70s.

Bennu might have clues into very important questions.

Photo: NASA/Goddard/University of Arizona/Lockheed Martin

“I’ve liked astronomy for as long as I can remember. I was a four or five-year-old boy and I recall saying that I wanted a rocket, or even a helicopter to go to Mars. So I’ve always wanted to be a scientist. For me, the process was pretty much the same as it is for any lover of science: my main goal was to learn as much as I could. And that’s the advice I give to young people everywhere.”

After finishing high school, he studied for a year at the Simón Bolívar University in Caracas and decided to emigrate, enrolling at the University of Kansas in 1977, where he got a degree in Astronomy. He’s been working in America as a teacher, researcher, and scientist ever since, and he tells me he never looked into the future, he just focused on working with determination and discipline.

“To get anywhere, you have to be focused on what you’re doing, doing the best work you can with the task in front of you at that time. Without haste, or hurrying things. If you stand out by always doing a good job, then everything else falls into place.”

His determination has paid off, because after getting his degree, he went for a Master’s and a Doctorate in Planetary Sciences. As a graduate student, he was appointed representative of the United Nations Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space. He has worked in observatories all over the world, including Arizona, Chile, France, Hawaii, Spain, and the Vatican. He is a lead investigator for the Hubble Space Telescope to study inactive comets and lead scientist at the Lunar and Planetary Laboratory of the University of Arizona. He has also collaborated with the European Space Agency and he was the recipient of NASA’s Ames Research Center Award for scientific achievements in 1987.

Bennu’s Secrets

Doctor Campins’s specialty are comets and asteroids, so I took the chance to ask him why they chose Bennu for this mission, and why that asteroid is so special.

OSIRIS-REx nearing Bennu, a task of extremely delicate accuracy.

Photo: NASA/Goddard/University of Arizona/Lockheed Martin

“We chose it for several reasons. First, because it had an orbit that was accessible and similar to Earth’s, and it possessed features of a primitive asteroid. In other words, it has organic matter, which is the main justification for the scientific side of the mission. The idea is to bring the sample to understand how life originated on Earth; which was the first step of complex organic matter becoming a living cell. This way we can deeply understand how life was formed. Also, this asteroid could come face-to-face with Earth in the future, so if we have to alter its course, it’s good to know how.”

To collect the samples, OSIRIS-REx tried a method NASA hadn’t tested until now: Touch-And-Go (TAG). First, the spaceship extends its robotic sample arm. Then both solar panels on the ship move in a “Y wing” configuration, which puts them safely above and far away from the asteroid’s surface. This configuration also places the ship’s gravity center directly above the TAGSAM collector head, the only part of the ship that’ll come into contact with Bennu’s surface.

“For us, this week’s maneuver was the most dangerous, most complicated one. Because we had to lower one of the ship’s arms. It was a very difficult procedure. The ship is very far from Earth for us to control it in real time, so we programmed it so that it would make its own decisions. As it got closer, we could compare the images it was getting with the ones it already had, and navigated with the asteroid’s topography. This way, it avoided collision with a large rock and reached the crater from where we took the sample.”

According to NASA, at 1:50 p.m., OSIRIS-REx turned on its engine to exit the orbit around Bennu. It extended its shoulder, then the elbow, and then the wrist of its sampling arm and moved towards the asteroid. After a four-hour landing, at an altitude of about 125 meters, the spaceship used its engines to reduce the speed of descent, tune in to the asteroid’s rotation and place itself in a clear area, at a crater on the northern hemisphere.

“The images are heavy and the antenna can only send a certain amount of data,” Campins explains. “But once the sample was taken, the telemetry started to arrive. I saw some of the images this morning. I saw when it touched the surface and the gases the ship shoots to liquefy the asteroid’s soil and place it inside the container. But go figure, if it usually takes a while here on Earth to get an image, think about one that’s coming from the other side of the Solar System, where it takes it about 20 minutes at light speed to reach the Earth. Once it’s here, it has to be downloaded little by little.”

A Crucial Discovery

One of the reasons Doctor Campins was able to convince NASA of sending a probe to collect samples on Bennu was because, in 2010, he discovered frozen water and organic molecules on asteroid 24 Themis and later on another asteroid, 65 Cybele, which supported the idea that water on planet Earth came from asteroids.

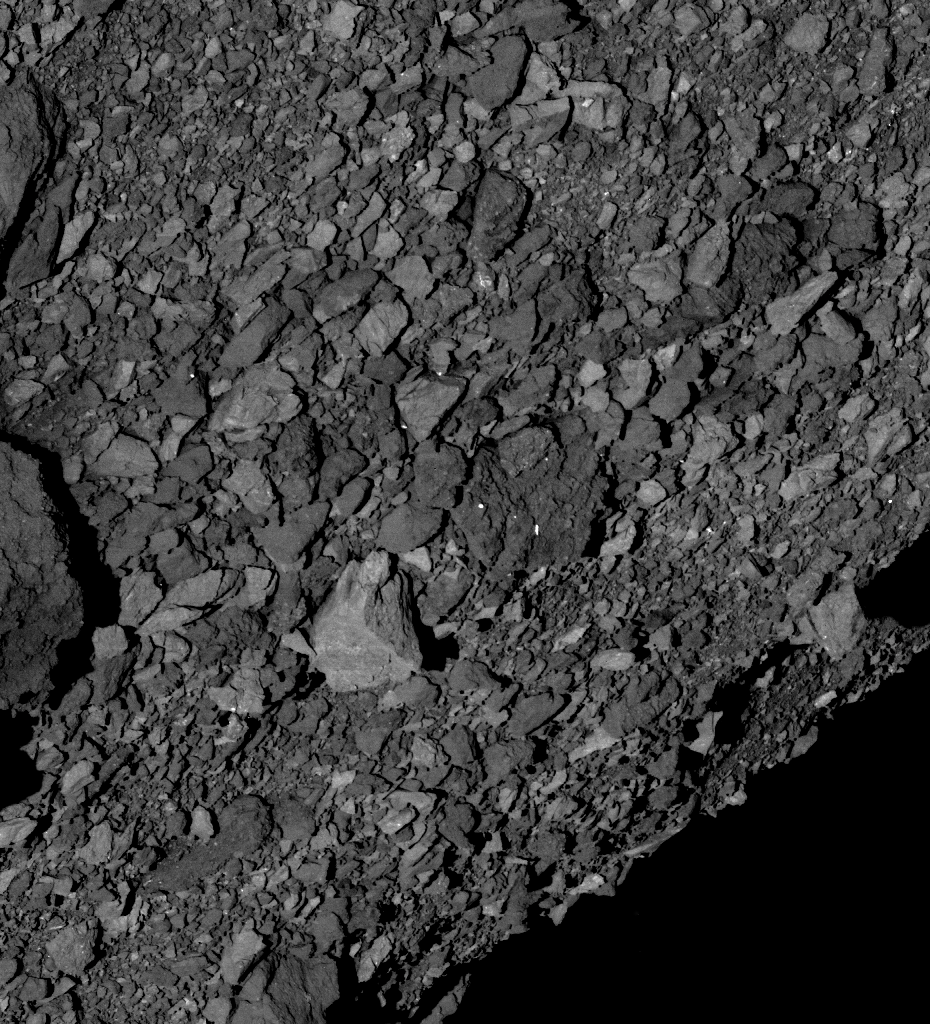

Bennu’s rocky surface as seen through the PolyCam on March 7th.

Photo: NASA/Goddard/University of Arizona/Lockheed Martin

“Two separate and independent teams found organic matter on two asteroids,” Dr. Campins says. “I was the leader in one of them. The first asteroid where we discovered organic matter was on 24 Themis, in 2010. I had just been invited to join a team that would work on the collecting ship. They mentioned that we had to prove to NASA that we could take samples from an asteroid, because no one had done it before, and I tell them, ‘Of course it has been done. Two teams did it and it’s going to be published soon in a journal.’ They were all shocked, because the journal asked us to keep it a secret. But since this was my new team, we could discuss it. I remember I was very happy about it, since they were going to help us on the mission, and they were even happier.”

At 8:30 in Tucson, Arizona, Dr. Campins tells me he has to leave for other commitments. But not without answering one last question, about the changes and discoveries that my generation will see in the upcoming years, as our grandfathers saw the first airplanes, and our parents saw the first moonwalk.

“In a decade or two,” he answers, “we’ll take the steps to obtain raw materials from space. For example, we could get water from asteroids, we’ll separate oxygen from hydrogen and we’ll get fuel. Colonization of the moon is coming. Manned missions to Mars are coming; a whole lot of surprises are coming that we can’t even think about. I hope very interesting changes are on the way, maybe some we can predict and others we won’t, but they’re changes that will come soon.”

I thank him and, before hanging up, he warmly says:

“To those over there, students, teachers and scholars, I tell you: don’t get discouraged. It isn’t easy making it in science, it takes years, time and dedication, but in the end, it’s beautiful and worth it. All that knowledge will be good for you. Whether the situation surrounding you is in your favor or not, knowledge in science and nature, and methodical studying will always be useful to us, in our actual lives, cultivating our spirits.”

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 22 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate