Marapolio: Monopoly with a Maracucho Twist

For many Venezuelans, and particularly for natives of Zulia State, there’s a board game that's pushing all the right buttons of quality and nostalgia

Photo: Carlos Fung

The world grew up hearing about Mediterranean, Oriental, Virginia and States Avenue. How about Raúl Leoni, Sabaneta, El Naranjal or La Limpia? If some of those names ring a bell, then you certainly have played Monopoly. If all of those names sound familiar, then, not only have you played Monopoly, you’re also from Maracaibo. How about a combination of both now?

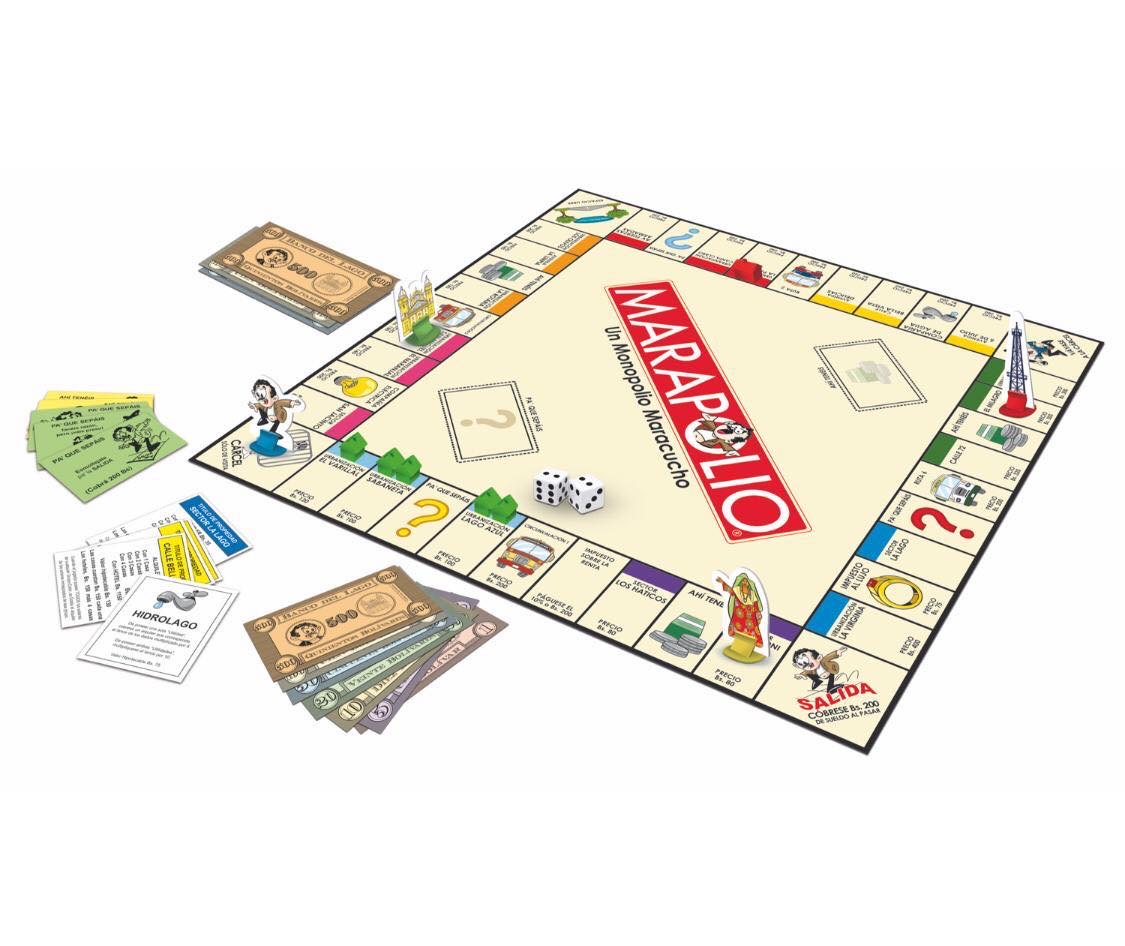

This week, lots of Venezuelans on social media stumbled upon the video of a delighted lady unboxing the Marapolio board game, a version of the classic Monopoly where the gimmick is the setting: Maracaibo, Venezuela’s second largest city. In the video, we can see the joyful appreciation of an obviously well-crafted product, full of a pride that’s not atypical for the average Maracucho.

As the resident Caracas Chronicles “Maracuchean”, I was given the task of taking a look at this unlikely product, and I found a whole history behind a simple cardboard game, with lots of things to touch my zuliano heart.

A Healthy, Curious Mind

Turns out, the video on social media didn’t begin to scratch the surface of the story. For anyone watching the clip, myself included, the perception suggested that this was a brand new product from the nostalgia-driven mind of some Zulian entrepreneur.

Well, not quite.

“This American version came out last year, becoming an immediate success.”

Photo: Carlos Fung

Marapolio itself isn’t new at all; its creator is Carlos Fung, a Florida resident. The game is produced by his Montesacro Editores and the first edition was released in 1996, a rudimentary version in Fung’s own words. There were changes in production through the years, with materials sourced from different countries at different times (Venezuela, Colombia, China) and this American version came out last year, becoming an immediate success with all 500 game sets being sold within the first month of release, both in physical stores and on Instagram. Carlos tells me that the video gave an amazing boost to demand, to the point where, for the time being, it cannot be met until March, when a new batch of Marapolios comes out.

But there’s something that the mild-mannered Mr. Fung told me that I got a kick out of. Carlos and his friends were avid board games enthusiasts and one day, playing the classic Monopoly with his pals, one of them mentioned how cool it’d be to play the game with Maracaibo streets instead. In tune with the behavior of a healthy, curious mind, Carlos took it upon himself to make the Maracaibo version by hand, and brought it to the next game night, much to the delight of his friends.

It was that group who suggested turning Marapolio into an actual business venture.

There’s No Monopoly on Monopoly

When I saw how well made Marapolio seems to be, one of my first thoughts was that there must be some kind of infringement with Hasbro, the company currently holding the rights to Monopoly.

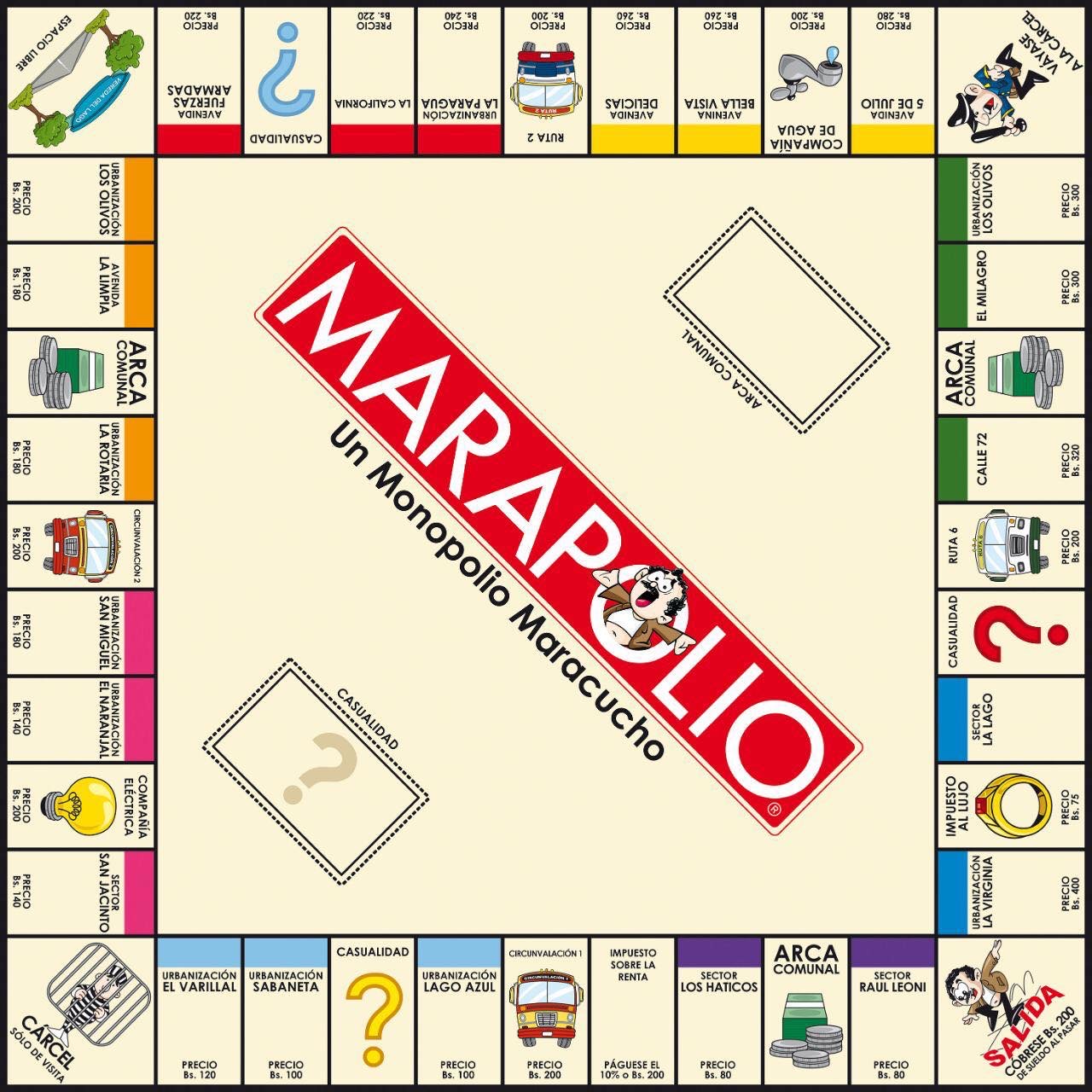

Yet Carlos explained to me that, even though Hasbro has ownership of Monopoly, the actual patent expired many years ago (the original game came out in 1935), meaning that you can make a board game with the mechanic of buying and selling property, as long as the name and features differ from Monopoly. That’s why you won’t find Baltic Avenue on Marapolio, but you have Avenida El Milagro.

As a matter of fact, this isn’t the first Venezuelan Monopoly; another version, so “Venezuelan” that all streets were from Caracas, was made and sold with success in the ‘80s. In that vein, this utterly Zulian version has similarities with real-life Maracaibo, which is not the city it was five years ago, let alone 25.

In the viral video, the lady describing “El Monopolio maracucho” is just so thrilled; I’ve never seen anyone that excited about the quality of a game manual—yet one thing that makes sense is the sequence of the streets on the board, which follow a coherent geographical configuration when compared to the actual city it attempts to recreate. Another nugget is how the priciest zones in the board are also true-to-life, with Sector La Lago and La Virginia being prime real-estate.

“This utterly Zulian version has similarities with real-life Maracaibo.”

Photo: Carlos Fung

Prices are in bolivars, more and more a quaint notion these days. Los Haticos, for instance, is amongst the cheapest, at Bs. 80, while La Virginia goes for Bs. 400. In reality, you can’t rent or buy property in Maracaibo with bolivars, but you can certainly buy for relatively low prices—finding a house in La Paragua, for instance, for 20 thousand dollars, a bargain considering that six years ago the asking price for a property in that middle class area could easily be 120 thousand dollars. In Marapolio, La Paragua goes for Bs. 240, well within the range of a savvy player.

I wonder if in the game, like in the actual city, players can refuse to take broken bills or painted-on bills. Everything sells for dollars in Maracaibo, but no one will take a single banknote with a slightly broken corner or a mustache drawn over George Washington’s face. In fact, people with damaged dollars can go downtown to sell them below their price. If you have, say, a $50 bill with a ripped bit, you can sell it for 75% of its value. Then the person who buys the banknote goes to Colombia, deposits the money and makes a sweet profit. Perhaps this practice should be in Marapolio, too.

Another feature Marapolio could add from reality is the shortage of smaller dollar bills that real life Maracaibo faces today, making you buy things you didn’t want at the store just so you can get change at the cashier. It’s like, Marapolio’s bank has no cash, so you have to buy a hotel in El Varillal when you only wanted a house in Indio Mara.

All in all, Marapolio holds up to the city, albeit romanticizing cultural aspects that have deteriorated with the passing of the neverending crisis we live in. Local players will enjoy “Ruta 6” and “Ruta 2,” staples in the bus routes of the city. Corpoelec and Hidrolago (state-owned electricity and water companies) also make an appearance; I’m sure that the jolliest of players will comically curse these companies, as they do in real life. The cards written in a local accent are also a nice touch.

It’s not a surprise that Marapolio is currently sold out, with so many Maracuchos living abroad and yearning for a city that no longer is. Any taste of that Maracaibo they left behind brings life to expats, who can take joy in the memories they carry, and this original spark of Maracucho creativity, so well-crafted and well-received, should be something to smile about for all Venezuelans, wherever we are.

It surely is to me.

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 22 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate