How Patricia Van Dalen Trapped the Colors of the Tropics

This Miami-based visual artist strayed away from the kinetic art path, in order to explore the light in public and private works of art that see the world with Venezuelan eyes

Photo: Carlos Pieruci Isava

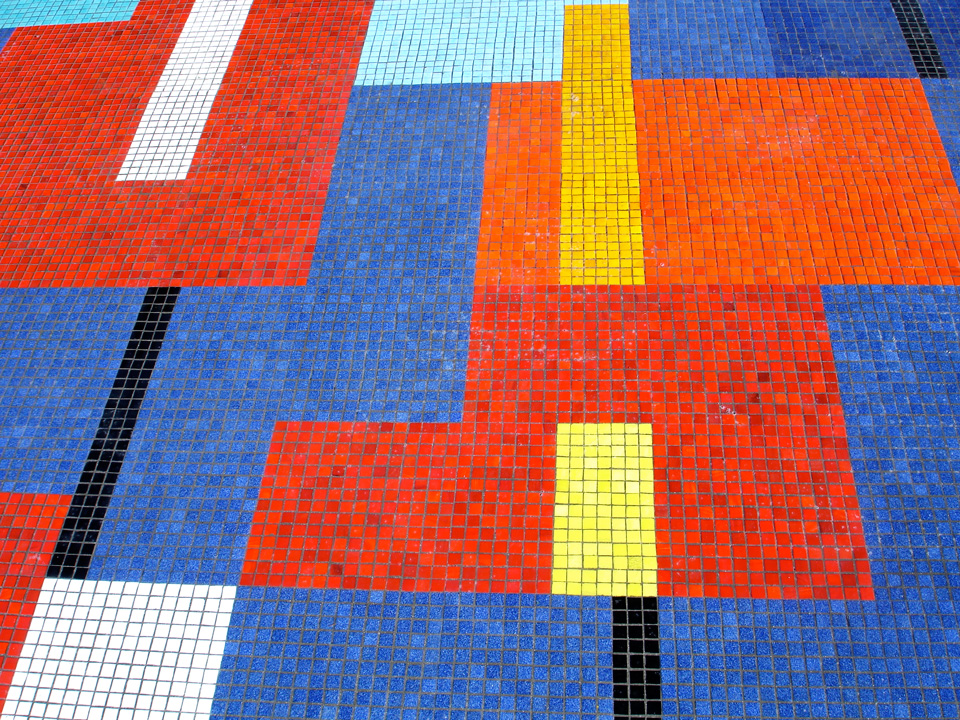

For many people in Caracas, the name Patricia Van Dalen (Maracaibo, 1955) could seem foreign and unknown. But her work is fixed in the mind of the people of the city: Jardín lumínico (2004-2005) covers a wall on the Prados del Este Highway, from Valle Arriba to Santa Rosa de Lima with big ceramic tiles —oranges, yellows and reds shattered over large blue and black spaces. “The color flashes were thought for those who’re driving at high speed on the highway,” says Van Dalen “and the pixels for those who’re going slow, trapped in traffic jams.”

Van Dalen’s fascination with color—made evident by the many shades of blue, red, yellow, green, black, white and orange filling the wall—has a long history. In 1980, Van Dalen met the Israeli artist Yaacov Agam (born in 1928) in Paris. He had established himself as one of the pioneers of kinetic art, alongside Jesús Soto, three decades earlier. “I was interested in how Agam was able to produce hundreds of tones with different shades. Like a hundred different stages between a magenta and a cyan,” says Van Dalen. However, Van Dalen didn’t arrive in the French capital with the plan of making art. She had just graduated in graphic design from the Neumann Design Institute in Caracas and she was in Paris as part of an education project funded by Corpozulia, alongside two other Venezuelan women: a pedagogist and a psychologist.

Courtesy of Patricia Van Dalen

Photo: Courtesy of Patricia Van Dalen

Van Dalen and her two teammates started to develop drawings and handbooks for a pedagogical concept created by Agam. But the influence of the Israeli master didn’t push Van Dalen on the path of kinetic art. “My work has never been related to kinetic art,” she says. On the contrary, she was looking to “reduce the possibilities, restrict them” by playing with color and sizes without allowing herself “total freedom”: tiles and monochromatic circles that all of a sudden crash with other colors; sharply colored collages, fragmentation and independent elements that come together to create a grater form.

Because of this, her work moves away from the rhythmic, rigidly organized forms of kinetic art and geometric abstractionism that prevailed in Venezuelan art in the 1950s and 1960s. Van Dalen works with multi-layered collages, cylinders with uneven sizes, paper, staples, aluminum shapes and ceramics. The developmental oil spirit of kinetic art stays behind and Van Dalen pushes the crack, the fragmentation, the fusion of the formal and the informal, and postmodernity upfront.

If we compare Agam’s From Birth to Eternity (1969-1972) with Van Dalen’s Jardin du Luxembourg (2008), we’ll see how both works share the width of its color range, but differ in terms of order: Agam engineered a rigid layout while Van Dalen managed chaos. “Disorder is the last thing kinetic art wants,” she says.

Van Dalen is interested in entropy, in measuring a system’s disorder. That’s what she did with the installation Luminous Gardens (2003), at Miami’s Fairchild Tropical Garden, where she put a hundred thousand flags in red and neon pink, which swayed in the breeze under palm trees, formed long lines over the green grass and reflected on a lagoon. Van Dalen wasn’t looking for an optic effect, but “the entropic relationship of a paradox: to represent nature with artificial elements.” She was remaking, with “poetic daydreaming,” the flowers growing in the countryside and “its entropy, for which I have great interest.”

A Fragmented Abstraction

“Agam project’s methodology showed me other ways of seeing the universe. I absorb everything with my sight,” says Van Dalen. In Paris, in the 1980s, she was taking names for her work from Frank Herbert’s Dune. She was fascinated with melange, the extraterrestrial spice that altered human conscience to allow space travel. “I used to imagine the effects of enhancing your perception. Just what I was trying to achieve with Agam’s educational project.”

This process makes her geometric expression in her work related to the moment she’s perceiving. “If I’m migrating, I can spend years working on the matter of trajectory, using not surfaces but lines, thinking about how we go from A to B,” she explains. This is what Van Dalen did with Estaciones/Stations (2019), a series of collages of pieces of ironed cotton paper, painted with acrylic and stapled together, every one expressing the color shades of places Van Dalen was traveling to, like New Mexico, Iznik in Turkey, Marnay-sur-Seine in France, but without glue to represent the impossibility of permanence.

Courtesy of Patricia Van Dalen

Photo: Courtesy of Patricia Van Dalen

This way, Van Dalen has explored abstraction through such diverse techniques like stapling, sewing, assembling solid color wood pieces, anything that could help her expose how relationships between structure and color can vary with a choice of material and shape. During this quest, she has found herself favoring increasingly flat forms. “I’ve been through almost all stages of the abstraction field,” she says. “Lyrical, expressionist, geometric, constructive and formalist abstraction.” How would Patricia Van Dalen define her own abstraction of controlled disorder and restricted possibilities? “Fragmented abstraction,” she says, thinking about the term for the first time. “I don’t intend to pursue perfection. I’m thrilled at disarticulating perfection.”

Similar to her leaps from one idea of abstraction to another, her work also expresses diverse forms: pieces for private residences, stained glass, decorative pieces, artwork for architectural projects, a color field on a botanic garden or a golf course due to the artist’s interest in “developing color on landscape.” Thus, Van Dalen is more than collage, painting and staples: it goes from ephemeral installations, passing through public art like the murals in Caracas or a wall at the Miller Learning Center at the University of Georgia—where she made Fragmented Light (2011) with a network of colored tape—to Jardines fragmentados (2011), a carpet manufactured at Ateliers Pinton in France for a house in Caracas. “This is a more inclusive approach for me,” she says about the diversity of the production forms in her work, “It defines my work more than a movement in particular.”

Caracas Disarticulated

“I take a lot from nature, from the cosmos,” Van Dalen says of what is perhaps her major inspiration. Words like “garden” and “universe” splatter her work. “Light also connects me with the spiritual,” she says of her other leitmotiv. A luminous Holy Trinity is the protagonist of one of her more expressionist pieces, La Trinidad V (1994), now part of a private collection in Holland. Light and gardens, translated into fragments or solid colors, is the artist’s personal way to represent Caracas, which she affectionately calls “the luminous city”.

Born in Maracaibo from a Dutch father and a Venezuelan mother joined by the magic of oil, Van Dalen–now based in Miami—has lived most of her life in Caracas. “I like to say that when the highway mural was inaugurated, I became a Caraqueña,” she says with joy. “Caracas’ urban landscape is found in my work. I’m fascinated by the variety of textures of its buildings, its balconies, the skin of its facades… such richness. I’m a person who’s always swallowing everything with my eyes, decoding everything I see.”

Her work Parque del Este (2016) shows one of these decodified approaches to the Caraqueño landscape: 171 aluminum tubes —manufactured by Venezuelan engineers living in Miami— oriented to create “that sensation of the forest at the north side of Parque del Este, close to the lake,” she says. But seen from above, the tubes mimic the map of the park and the colorful silhouettes created by Brazilian master Roberto Burle Marx. In this piece, the shape of the park emerges in shades of red, pink, orange and green from black pebbles inside the house of a Venezuelan family in Florida. A nostalgic ode to the country left behind.

“I’m continually giving shape to the memory of the jacarandas at Parque del Este, the araguaneys, the apamates (pink pouis), the Alta Florida neighborhood with those jabillo seeds dropping from the branches, that light that hits your eyes when you make a curve on those hills in Caracas or that warm mist that wraps everything, the hill slum houses, the informality of those houses and their particular texture. Everything that Caracas offers visually is apotheosis.”

Van Dalen: a Caracas Icon

The decoding of Caracas is also present in the mural. “I take the reflection of the Ávila, the dialogue with the golf course, and the big yellow sun on the access ramp as a sort of movie trailer of the universe,” she says about the yellow and red star amid a sea of blue tiles.

Van Dalen finished the first phase of Jardín lumínico in 2004 and the second one in 2005, replacing what had been a grey wall splattered with graffiti. She was responding to the urban renovation launched by then Baruta mayor Henrique Capriles, who opened a contest to develop an art project for the site in 2001, after BAK Estudio de Arquitectura designed a new walking path between the highway and a hill. Van Dalen competed against ten other artists. Her proposal was chosen by a jury that included people like Sofía Ímber, Pedro León Zapata, the architect Jimmy Alcock, mayor Henrique Capriles and curator María Luz Cárdenas.

“I use Photoshop a lot,” Van Dalen says. For the mural, she processed pictures she took of her own painting and created bands on AutoCAD, from which she elaborated color pixels. Every pixel was turned into a tile: 70,000 of them, actually, made at Cerámica Carabobo, to cover 1,200 square meters. Van Dalen went to the factory in Valencia to make the final decisions on the colors. “I had to restrain my project’s draft to squares in fourteen colors. A good exercise in reduction.”

Courtesy of Patricia Van Dalen

Even though the ceramic tiles are made to last, the mural has suffered in recent years from the general decay of the urban landscape in Caracas. Some tiles have cracked or fallen, and in 2015 some people sprayed “PSUV” ( United Socialist Party of Venezuela) all over the mural and stuck posters of chavista candidate Haiman El Troudi. The municipality used paint thinner to remove the political slogans, but dark and diffuse stains can still be seen on the yellow tiles.

In 2016, Van Dalen repaired a two-meter segment that was damaged by car crashes and big holes and bumps caused by the hill’s creeks despite the mural’s draining system. “I had to change the original design because the darkest blue had run out,” she explains.

In fact, it’s likely that future repairs will require a change of color, given the slim chances of replicating the original tiles in the current conditions of the country. “Any work must be coordinated with me, it’s my work,” Van Dalen says. “I respectfully ask the municipality to remember that any changes on the mural must be authorized by me.” About a year ago, Van Dalen talked about future restorations with Baruta but nothing came out of it. Then, a few hours after the first draft of the Spanish version of this article was completed, mayor Darwin González wrote to Van Dalen with the interest of repairing the mural. “It’s the mural, it’s an entity of its own,” says Van Dalen about the simultaneity of the mayor’s message and the publication of this piece.

Jardín lumínico isn’t the only iconic work by Patricia Van Dalen in Caracas. In 2003, artist Diana López —then director of Cultura Chacao— commissioned a mural for the Pajaritos barrio, a low-income community in the municipality. “I wouldn’t do an abstract work because the place is called Little Birds (Pajaritos). I’m going to work for the community here.” The result is a huge multicolored tile mural with tropical birds perching over abstract floating shapes, that evoke both the big leaves of the city’s trees and Calder’s clouds in Ciudad Universitaria. The birds represent species flying in northern Caracas, which Van Dalen took from a book published by Chacao: two azulejos (blue-grey tanagers), one querrequerre, one cristofué (great kiskadee), one troupial, one pico de frasco (groove-billed toucanet), one olive woodpecker, one macaw and a yellow-crowned amazon representing Roberto Antonio, the pet parrot of a near car shop.

Sixteen mts. long and two mts. high, Mural Pajaritos (2003) created big-scaled birds to amaze the children of the area. When López saw the design, she decided to move the original location to a more visible wall, right at the entrance of the slum. A group of artisans who worked on the murals of Ciudad Universitaria was in charge, among which was Italian master builder Antonio Foghin, an Italian immigrant from the northeastern region of Friuli. Once the mural was finished, Patricia—always outstanding with her red hair and her blue eyes— took a picture of herself and the kids she had in mind when designing the birds. Almost twenty years later, the mural and its large pajaritos are intact: they’re in the care of a community that appreciates and values them.

“My work is vast, but little known, there are no books on it and just a few publications,” says Van Dalen. Maybe, on paper and online, she’s gone rather unnoticed. But it’s different in Caraqueños’ imaginarium, where her pixelated solar universes and her giant birds are deeply embedded. Or even farther east, in the Caribbean village of Río Caribe, where her mosaic Jardín de calas (2006) covers a colonial square among tall chaguaramo palm trees. Van Dalen isn’t really an unknown artist, she’s a thousand-colored fragment in the collage we call Caracas.

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 22 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate