Those Who Leave Venezuela Carry a Stamp on Their Forehead

Among the six million+ Venezuelans who have left their country, there are displaced citizens and refugees; but institutions, politicians, and social agents decide to deny them this status, feeding a vicious circle of human rights violations

Photo: Sofía Jaimes Barreto

In the treacherous waters between Trinidad and Venezuela, a patrol boat of the Trinidadian Coast Guard opens fire against a boat filled with Venezuelans who have paid what they don’t have to try and enter the island country and a baby is murdered in the incident, which will be then justified by the Prime Minister.

In the Darien Gap, the impenetrable jungle isthmus that separates South America from Central America and has inspired horrific travel stories for centuries, a young Venezuelan mother falls into the waters of a canal and drowns, as other migrants from other countries who are trying to reach the north with her are unable to save her.

In the most arid desert on Earth, in northern Chile, heading to bordering towns where there are people digging trenches and torching foreigners’ belongings as if it were a holy war in medieval Europe, other Venezuelan migrants succumb to nighttime cold or daytime dehydration, when they’re abandoned by the coyotes in the middle of nowhere.

And in the Río Bravo, or Río Grande, mentioned so often as the northern limit of Latin America, an eight-year-old Venezuelan girl slips off of her mother’s hand and gets lost in the current.

Read Part I of Los Migrados: When You Uproot Your Entire Family Tree

All these scenes, which have become as common as the sunken boats or the girls disappearing forever, are happening on borders where those human beings aren’t welcomed, neither as refugees nor as passing travelers. They take those natural risks because they insist on crossing those borders, paying coyotes to surpass a legal barrier through clandestine ways. They do it because they have enough reasons to leave their country of origin, and have embraced the hopes that their destination will be worth the financial, physical, and emotional cost of the journey (although they wouldn’t have made the trip or that particular route had they known the tragedy ahead of them, of course).

Crossing the Venezuelan border with Colombia isn’t safe either, but it carries fewer risks. If the border is open, Colombian agents have several procedures to follow on handling migrants crossing the line, so migrants don’t have to deal with a river current (as they’ve done right there in Táchira when the border is closed), run the risk of dying from dehydration in the desert (not even going to the arid Maicao, in Goajira, where there are refugee camps), or get lost in the jungle (reaching Arauca o Puerto Carreño is accessible for people in Apure or Amazonas). Colombia has spent a lot of time dealing with an active border and has taken measures to handle the largest flow of Venezuelan migrants in the world, crossing into Colombia to stay (as almost two million people have done) or to move on to other destinations in South America.

The border in Gran Sabana is even more organized. Venezuelans crossing to Brazil through Paracaima, via Boa Vista, are received by a medical, legal, and military operation, which identifies their needs, plans on whether they’re staying in Brazil or moving someplace else, and what sort of migrants they are. But what separates that from other land or maritime borders to the south or the north, in the rest of Latin America, the Caribbean, or the United States, is that as far as Brazil is concerned, any Venezuelan entering is considered, from the get-go, someone who is migrating out of need. Not an enemy they must repel.

The sea, the jungle, the deserts, and the rivers are formidable obstacles, but what determines things are the bureaucratic obstacles, orders received by border agents for when a Venezuelan comes by. And that is what makes the difference in conceptualizing a displaced person, a refugee, and a migrant, because depending on those concepts are migrant policies made, allowing us, or not, to pass.

…

Once they leave the country, among the many problems migrants have to deal with is how they will be classified. A sort of invisible stamp on their forehead will determine their level of vulnerability.

Someone is usually considered “displaced” when they were forced to leave home, pressured by armed groups or as a consequence of a disaster, and must move to another place within the same country. When Venezuelans are forced to cross the border, then doubts arise on what seal should be stamped on the forehead of our people. The severe food insecurity, the humanitarian emergency, and the collapse of services that have pushed and still push many Venezuelans to leave, even if they don’t have the means to do it in a safe way and without any guarantees about their possible destination, are not considered reasons to obtain refugee status, which grants the protection a State is mandated to provide for those under that status.

The “refugee” category, established in international legislation and translated in national laws and procedures to follow on borders after a State signs a convention or a treaty, commits a government to protect people who fall under that category. There are two international agreements that interest Venezuelans: the 1951 Refugee Convention, whose reach was expanded by its protocol in 1967, and the Cartagena Declaration of 1984.

Read Part II of Los Migrados: How Violence Separates or Displaces Venezuelan Families

According to the Convention, signed at a special conference of the United Nations, a refugee is someone who has been forced to leave their country because of persecution, war, or violence. That person has valid reasons to believe their life is in danger because they belong to a particular social group (an ethnicity or a religion, for example) or because of their nationality or political opinions.

This classic definition fits those who can prove they have been victims of political persecution: political prisoners and victims of repression who have obtained political asylum in countries who have ratified the Convention, as in the case of most Latin American countries. But it doesn’t fit the large majority of Venezuelans who left as the result of pressure of a violent nature that can’t be proven, or simply because they understood that if they didn’t leave to find work in another country, their kids would starve to death.

According to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, UNHCR, “when we say ‘refugees’ we are talking about people who are running away from war or persecution and have crossed an international border. We talk about ‘migrants’ when people are moving for reasons not included in the legal definition of refugee.”

In other words, if you’re not running away from war or persecution, you’re not a refugee, therefore you can be deported back to your country, you can be denied access, and there’s no international obligation to tend to you outside your basic rights, the same ones a regular traveler passing through an airport would normally have. That text on the UNHCR website we quoted in the previous paragraph, also says the following: “Migrants choose to move not because of a direct threat of persecution or death, but mainly to improve their lives by finding work or education, reuniting families, or other reasons. Unlike refugees, who cannot safely return to their country, migrants continue to receive their government’s protection.” But what protection is given by the de facto Venezuelan government to their migrants?

“When the international legal framework was structured to protect people in situations of human relocation,” Betilde Muñoz-Pogossian, director of inclusion in the OAS, explains, “situations like today’s didn’t exist, so they are outdated.” The 1951 Convention, which organized the functioning of the newly founded UNHCR, regulated the circumstances to grant asylum based on what the world had witnessed during World War II. It was signed in a less globalized world, where the international community had just learned that it had to protect people who were vulnerable to genocide and seasonal workers, like Mexican seasonal laborers in the United States. In the following decades, with more people moving and other factors driving that mobility, those post-war agreements have proved insufficient.

That’s why the Cartagena Declaration was made in 1984, at a congress by experts from Central America, Mexico, Panama, Colombia, and Venezuela. That Declaration broadens the refugee definition, to include all who have been forced to leave their country because their life, safety, or freedom is under threat by general violence, foreign aggression, internal conflict, mass human rights violations, or other circumstances that break with public order. A definition that brings to mind repression, nationwide blackouts, food shortages, humanitarian emergency, and which can be easily applicable not just for migrants, but for Venezuelans in general; in the 2017 protests, the 2019 power outage, and today.

The point is, the Convention is binding—every country who signed has to translate it into law—but the Declaration isn’t. Although the Inter American Human Rights Commission and UNHCR have asked for countries in the region to tend to Venezuelan refugees in accordance with the terms of the Cartagena Declaration, only two have complied: Brazil and Mexico.

Brazil launched Operaçao Acolhida in 2018, with which the Brazilian authorities have provided identity documents and assistance to tens of thousands of Venezuelans who have crossed the border, acquiring legal work status. They help migrants find work where they’re needed, they have received health care, and more than a quarter of a million people have settled in different parts of huge Brazil… all because Brazil assumes that all Venezuelans are refugees by default and deserve basic protection.

Mexico, on their part, has used the refugee definition from the Cartagena Declaration to give refugee status to thousands of Venezuelans who requested it. But the Mexican border isn’t like Brazil’s for those who arrive by plane or, worse yet, by land: just like with migrants from many other countries who want to stay in Mexico or, more commonly, try to enter the United States, Venezuelans are facing more obstacles to enter the country. After experiencing more refusals of entry at the border, Venezuelans now need a visa to enter Mexico, which, for most, is almost impossible to obtain. Mexico can grant asylum, but first you have to enter, and in their eagerness to help the United States manage their migrant pressure from the South, Mexico has created a wall for Venezuelans (and for other nationalities), a lot taller than the one Donald Trump wanted to build.

Countries like Mexico, says the joint director of UNIMET’s Centro de Derechos Humanos in Caracas, Victoria Capriles, see migrants as a national security issue, “as someone who represents a hazard for my people, and not a human safety issue.”

Capriles agrees that the critical point is about countries complying or not with what’s established in the Cartagena Declaration: “That’s why Operaçao Acolhida is so different. Brazil sees those people as forced migrants, not as economic migrants. Mexico approves almost all asylum requests from Venezuelans, but since its foreign policy is tied to the United States, it now imposed a visa that affects the right to asylum. The rest of the countries that don’t apply the Declaration contribute to the perception of Venezuelan migration as an economic one. Even the statute in Colombia sees them like that, and that generates serious flaws in its execution.”

…

Wouldn’t it be easier for everyone in the region, and not just Brazil, to put in practice the Cartagena Declaration in the case of Venezuela?

Not necessarily. A State that sees Venezuelans as refugees has to treat them as such, and that costs money: you need health and identification staff, an army of social workers; you have to organize transport, food, outpatient facilities, emergency lodging. In economies that already were in serious trouble when the pandemic began, this is an expense that almost no country in South America can afford: money doesn’t abound in the public treasuries, and voters’ patience is even thinner when it comes to spending money on foreigners when they aren’t getting what they want in public services, government aid, tax reductions, etc. Just as it’s happened on the eastern and southern borders of Europe with the intense refugee flow fleeing from starvation and wars in Africa and the Middle East, governments in Latin America and the Caribbean demand financial aid from richer countries to manage the Venezuelan migration, while they strengthen security measures and deal with xenophobia. That’s where geographical, economic, and public opinion differences become clear.

After decades of seeing Venezuela as the rich neighbor where petrodollars avoided the predicaments the rest of the region was going through, Andean, Caribbean, and Central American societies are now wondering why they have to pay for the Venezuelan collapse. However, “in my interaction with people from government and development agencies,” Betilde Muñoz-Pogossian says, “what I’ve felt is an acknowledgment of solidarity towards us as much as they can, with what they have, because what Venezuelans are going through isn’t our fault. But it may be a different issue with the communities.” In any case, the differences between countries like Brazil and Argentina, which are able to welcome Venezuelan professionals in provinces where they’re needed the most, and the likes of Trinidad or Chile which are militarizing the borders, there’s also a precedent disparity: different institutional histories. Brazil is a State with a better-shaped bureaucracy, larger, better trained, and more efficient.

Read Part III of Los Migrados: The Elastic Families of Venezuela’s Forced Migration

There’s another cultural element that translates into the political and institutional decisions to consider Venezuelans as displaced and refugees or not: the history of each country as a migrant issuer or recipient. Brazil and Argentina have a long history of receiving migrants since the 19th century; on the other hand, Colombia, Ecuador, or Peru have been migrant-issuing countries, where migrant policies have been designed to protect their immense diasporas, Muñoz-Pogossian explains, not to host immigrants. “These countries hadn’t built social pacts on how to welcome foreign people, then this landed on them.”

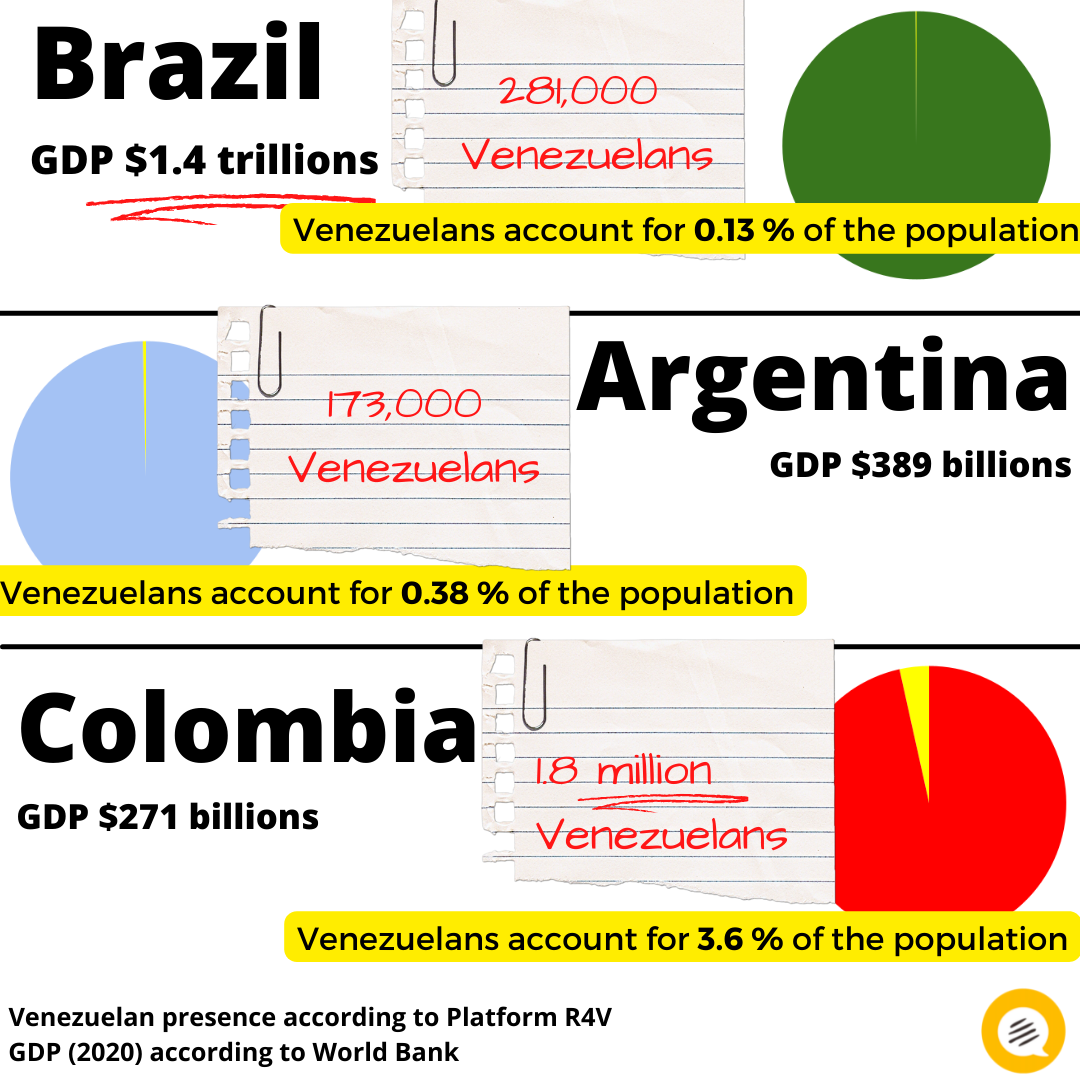

You have to take that into account to understand why Brazil and Argentina have handled Venezuelan immigration in such a different manner than other Andean countries, or Panama, or the Netherlands Antilles, and Trinidad and Tobago. Lastly, for a nation the size of Brazil it’s easier to protect a quarter of a million of Venezuelan migrants, with all the challenges on safety and poverty that Brazil has, than for a country like Ecuador, where there’s over half a million.

For Ligia Bolívar, an associate researcher on migration at UCAB’s Centro de Derechos Humanos in Caracas, the thing is quite simple: “The problem of denomination is about dodging responsibilities. The truth is that these are people who need international protection as soon as they leave the country, because they didn’t want to leave: they had no other choice.” It shouldn’t be that complicated, this expert claims: UNHCR states that a person is a refugee the moment he or she sets foot outside their country against their will, therefore, states only need to recognize the refugee status this person already has.

In the orientation notes from March 2018 and March 2019, UNHCR suggested to governments that, considering the context of Venezuela, they should apply the more ample refugee definition given by the Cartagena Declaration. This Declaration is the product of a refugee crisis, the one caused in the early 1980s by the armed conflict in Central America. “At the time,” says Bolívar, “a lot of people were leaving their country in a way that didn’t qualify in the refugee definition from 1951, but they were leaving because people were shooting each other right next to their house.” Since this wasn’t included in the definition, the Declaration was written to include conditions that, as UNHCR says, aren’t like the war in Syria, but do apply to Venezuela today. “What has to be clear is the country’s profile and that’s what Brazil has done through their Refugee National Commission. They came to the conclusion that there’s a massive human rights violation situation in Venezuela, which makes its citizens qualify as refugees. This diagnosis was extended for two more years.”

Bolívar points out that it’s concerning that the UNHCR doesn’t resolve the confusion in the definition of refugee. That the UN Secretary-General appointed an official to overlook the situation of Venezuelans relocating, with the mandate of coordinating UNHCR with the International Organization for Migration, is proof that the United Nations wants to settle by considering most of these Venezuelan economic migrants, not refugees. “And they’re not migrants, because there’s a consensus that they’re people who need international protection. They wouldn’t be a financial burden for hosting countries because that’s what international cooperation is for. Receiving countries want the money for international cooperation, but they won’t give Venezuelans refugee status. That’s the eternal gridlock of this problem”.

“The Coalition for Human Mobility of the OAS has already begun this discussion, but the ambiance isn’t ripe yet for that,” Muñoz-Pogossian tells from Washington, D.C. She admits that the sense of urgency has decreased. “Venezuelan migration has been normalized, it became another element of the context, and it already was like that before the new global refugee crisis created by the Ukraine invasion. This is an important obstacle when it comes to getting more funds to help those countries who are receiving Venezuelans.”

Victoria Capriles says that since the international community doesn’t want to see us as forced migrants, they haven’t released more resources. “UNHCR is doing as much as it can with Venezuelan migration. And these states aren’t getting the help they need. It’s a lack of ethics issue, of empathy by the governments.”

Is all this true? Well, let’s look at the numbers. Research done by Dani Bahar and Meagan Dooley for the think tank Brookings revealed that as of 2020 the Syrian exodus had received almost 21 billion dollars in aid, and the Venezuelan, though of a similar scale, 1.5 billion dollars. In other words, the international community had contributed $3,150 for every Syrian forced migrant, $1,390 for each South Sudanese forced migrant… and $265 per Venezuelan forced migrant.

Of the 1.3 billion dollars needed for Venezuelan forced migrants in 2020, only half was raised. In June 2021, when Canada organized the International Donors Conference in solidarity of migrants and refugees of Venezuela, it only managed to pledge donations for 954 million dollars, plus 600 million in concessional loans.

…

Betilde Muñoz-Pogossian says that we have to keep insisting on governments to use the broader definition of refugees from the Cartagena Declaration, and that they acknowledge the refugee status prima facie, as Brazil has done. In other words, to see Venezuelans as a human group forced to seek asylum—as we see today in the case of Ukrainians crossing the border with Moldova and Poland en masse—instead of making each Venezuelan, case by case, prove they need asylum, especially if it’s obvious when, for example, two little brothers without an adult claim that they’re looking for their mother, or a rural or Indigenous family is clearly on the brink of survival.

The problem isn’t that what’s going on in Venezuela isn’t known. The international community is pretty aware that Venezuela has forcibly displaced people, forced migrants. But the defensive traditional view of the migrant hasn’t diminished, and as Capriles says, that is the breeding ground for xenophobic discourse and policies, so it ends in a worse unprotected status: migrants aren’t being protected by their country of origin or their hosting country, and that’s why we see this new movement to a third country that is propelling the migrant crisis in Central America. “A Venezuelan woman who died of a heart attack in Costa Rica was coming from Peru, where she was living until she decided she had to go again, not back to Venezuela but to try to reach the United States. What we’ll continue to see is a surge of Venezuelan migrants heading North, by land, trying to cross the Darien Gap, to reach the United States through Mexico.”

This status quo based on denying displaced people their refugee character, of overlapping that label with the one of “migrants” to avoid taking in commitments, isn’t sustainable.

“Temporary solutions won’t solve the issue, we have to look for long-term solutions,” Ligia Bolívar says. “Finally, Colombia understood that by creating a mechanism of ten years’ protection, instead of two. I wish other countries would do the same. Even if tomorrow there was a change of government in Venezuela, people won’t turn around and run back, because they know they will find the same hardships, shortages, violence, social insecurity, and bad schools. They will wait.”

“Venezuelan migration isn’t a temporary phenomenon,” Victoria Capriles points out. “Those six million won’t come back. In the best-case scenario, one million people would return. And regional governments have to accept that fact. Colombia has to know that the protection statute is permanent and not temporary. Closing the borders doesn’t stop migration, it only makes it unsafe and irregular, and it increases the rights violations of these people who are moving.”

Closing the borders produces more painful scenes, which the media narrates over and over again until it becomes an echo that no one listens to anymore.

You can find a Spanish-language version of this article in Cinco8.

Read Part I of Los Migrados: When You Uproot Your Entire Family Tree

Read Part II of Los Migrados: How Violence Separates or Displaces Venezuelan Families

Read Part III of Los Migrados: The Elastic Families of Venezuela’s Forced Migration

Los Migrados was made with the support of Factual.

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 22 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate