Chavismo Goes After the Caracas Lion

The City Council of Libertador municipality in Caracas, with a PSUV majority, approved a resolution to change our capital’s anthem, its coat of arms and flag. But it’s not the same as other examples of revising history.

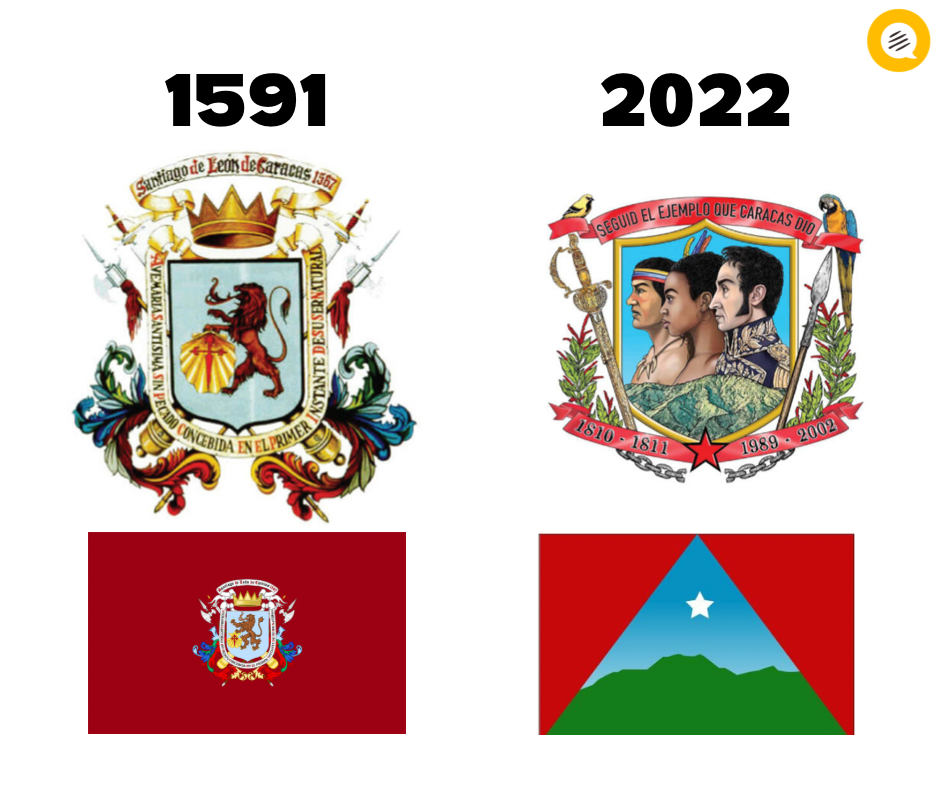

Last week, the municipal authorities of Caracas announced a new coat of arms and flag for the city, replacing the iconic lion imagery associated with the capital’s existing flag and shield. Chavista mayor Carmen Meléndez’s tweet announcing the new designs was followed by uproar across Twitterzuela, as residents of Caracas expressed their outrage that the city’s historical legacy was being erased.

Chavismo rhetorically justifies the need for new symbols by citing the colonial legacy associated with the official name Santiago de León de Caracas, which was allegedly chosen by the conquistador Diego de Losada when he founded the city in 1567.

Replacing or altering national symbols tied to colonialist imagery isn’t unique to Venezuela, though. Over the last few years, we’ve witnessed movements, mainly in Western countries, to remove statues, images, and names associated with the evils of slavery and brutal colonialism. Some claim that problematic historical figures shouldn’t be celebrated, while others believe these are undue attacks on key figures that are part of the history of their cities and countries.

Changing a coat of arms or a flag isn’t inherently a bad idea if done with the proper consensus and deliberation. Maybe caraqueños should consider challenging the colonialist legacy tied to these symbols—but that’s not what’s happening here. In this case, these changes in national symbolism are designed to serve as rhetorical ends rather than correct historical injustice.

As expected, the newly approved flag and coat of arms were charged with communist-style national imagery that glorifies Chávez’s so-called revolution. But these kinds of efforts are not new for chavismo, which has been replacing national symbols for over 20 years. The national flag and coat of arms, for example, were altered on Chávez’s orders, and the León de Caracas, a historical monument of the city, was replaced in 2018 with a sculpture of the Indigenous chief Apacuana. Not to mention the bizarre proposal in Chávez’s failed constitutional reform package to officially rename Caracas to include “Birthplace of Bolívar and Queen of Waraira Repano.”

Graphic design is my passion.

Ultimately, though, these attacks on national symbols are part of a legitimization strategy for the government. The new symbols for Caracas, for example, use the guise of anti-colonialism to distance political discourse from the regime’s own failures, all while generating political controversy with little relevance to the everyday life of Venezuelans.

Appropriation of Indigenous People

First, the party uses the changes to claim the moral high ground, centered around the fiction that chavismo cares deeply about Indigenous rights and history. In practice, though, the chavista government has severely neglected and even actively suppressed Indigenous participation in the political system. In 2016, for example, the Supreme Tribunal of Justice (TSJ) barred three elected Indigenous deputies from Amazonas from being incorporated into the National Assembly because it would have given the opposition a super-majority in the incoming parliament.

Additionally, establishing the Mining Arc in 2016, a large swath of the Amazon designated for extensive mining, has devastated local Indigenous groups. Indigenous communities were not consulted at all and, due to illegal mining and extreme poverty, many Indigenous people have been forced to work in slave-like conditions in illegal mines to survive. The nationwide economic crisis has also pushed the Warao and Wayúu groups, unable to access food and medicine, to leave their ancestral lands for protection in Brazil and Colombia.

The sidelining of Indigenous peoples by the Venezuelan government belies its proclaimed concern for their historical mistreatment. There are many examples of cities across the world making good-faith attempts at recognizing Indigenous symbols in their flags and coats of arms. Montreal, for instance, modified its flag in 2017 to include Indigenous symbols alongside the symbols of the “founding peoples” of French, English, Scottish and Irish descent. In our case, though, the appropriation of Indigenous empowerment is merely an attempt to legitimize a morally bankrupt regime, not raise the voices of the historically abused and politically excluded.

Political Distractions

These new symbol changes are also distractions from the regime’s governance failures. They fuel controversy in areas of the political sphere that are irrelevant to Venezuelans’ day to day. Instead of having people talking about widespread corruption and inflation in a dollarized economy, it’s more convenient to have people debating whether it’s appropriate that symbols with ties to colonialism must be erased from public view.

It’s why the new designs for Caracas are over-saturated with imagery that borders on caricature.

The coat of arms, for example, features a quote from the national anthem, Bolívar and his sword, a spear, a black woman, an Indigenous man, the turpial (national bird), and the guacamaya (which might as well be the de facto bird of Caracas). Then there are chavista elements, like the red star of Soviet origin, appropriated by the Bolivarian Revolution, and dates considered “victories” by chavismo (1989 – 2002) unironically placed alongside the years of independence (1810 – 1811).

The melding of party and national symbolism that’s so successful at generating outrage because the changes are a reminder by the government to its citizenry that chavismo is here to stay, not just as a political movement but as a foundational reworking of Venezuela itself. The subtext is clear: the old Venezuela is gone for good. And while it may be tempting to think that the government is making these changes sólo por joder, there’s more to it.

The comical excess of symbolism melded with chavista iconography evidences a desperate need for legitimacy in a moment of unclear ideological direction within the regime. This is important because chavismo continues to label itself a leftist, revolutionary force while governing in a way that is the antithesis of extreme-leftist ideology. Just look at the fetishized consumerism that Bodegonzuela embodies with its lavish imports, shiny new Toyotas, high-end restaurants, and luxurious parties. Symbolism is important to the regime because it allows the government to hide its failings behind a superficial layer of socialist ideology.

The regime feeds on the polarization generated by these changes, aligning itself with a decision that may have legitimate moral justifications but comes off as disingenuous and self-serving. Most disappointing, though, is how these decisions rob Venezuelans of the opportunity to grapple with our country’s colonial past through nuanced political discourse and develop the kind of consensus necessary to begin making changes to problematic national symbols. If new symbols are simply imposed, they have no power. After all, symbols are ultimately worthless if people are not invested in their meaning.

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 22 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate