Illicit Trade Represents 21% of Venezuela’s GDP: Is This Our Post-Oil Future?

Research by Transparency International Venezuela and Ecoanalítica estimated the size of the criminal economies that deal in gold, drugs, and gasoline with the enthusiastic participation of a corrupt State

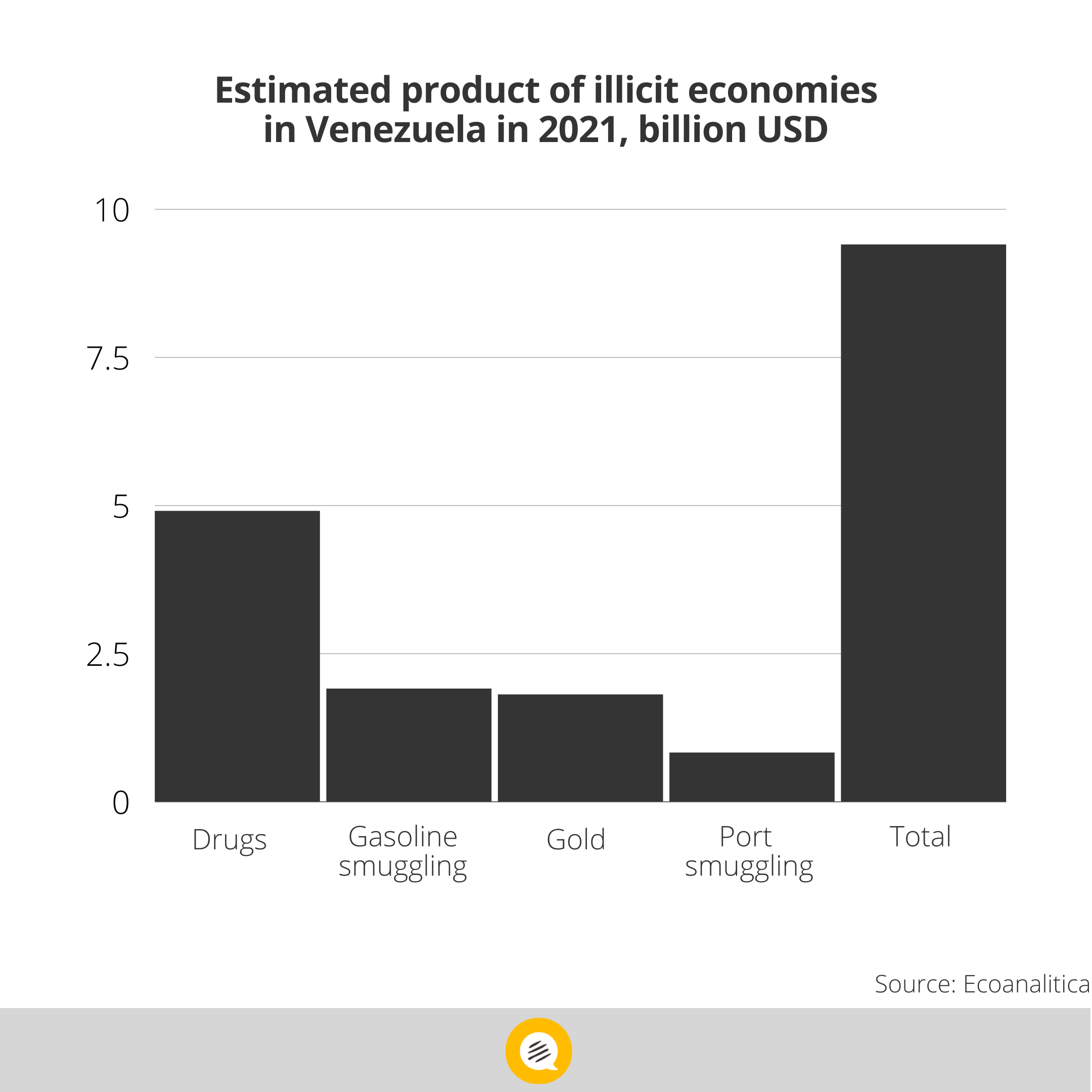

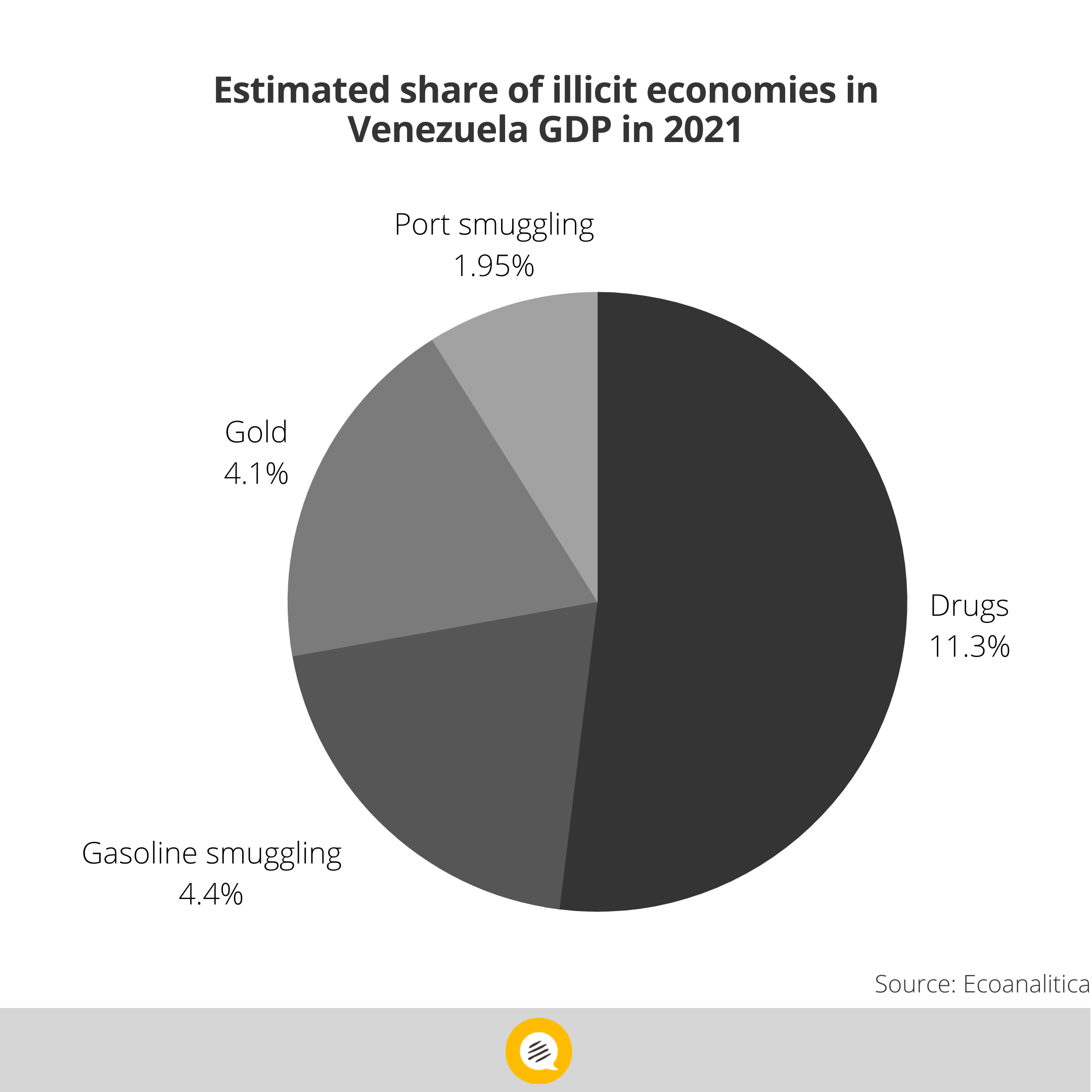

After calculating the current annual worth of drug, gold and gasoline trafficking and port smuggling in Venezuela, a study by the local chapter of the anti-corruption nonprofit Transparency International—with estimates from Ecoanalítica, a Venezuelan economic consulting firm—concluded that these illegal economies made up 21.74% of Venezuela’s GDP last year. “This means they are more powerful than any other economic sector right now, including oil,” says Mercedes De Freitas, Transparencia Venezuela’s executive director. “And we are talking only about the size of four of these economies, the most important ones. There are other illicit trades: certain types of food smuggling, diesel smuggling, cooking gas trafficking, human trafficking or timber trafficking, which could be important in some regions.”

De Freitas thinks that institutions have been put at the service of small groups that control justice by generating lax spaces where all sorts of illicit trade can flourish. “Illicit trades are not external to the State: they are organized and promoted from within the State.”

This “black economy” of illicit trades, as the study defines it, is part of a bigger “underground economy”; the set of undeclared economic activities that escape state administration and official statistics, encompassing both the informal economy—which has increased since 2014, mostly because a reduction of public sector jobs—and the illegal economy.

The black economy “has worsened in the last years in Venezuela,” says economist Asdrúbal Oliveros, director of Econalítica. When the firm started these calculations in 2016, illicit economies accounted for 10% of the GDP. Now they are twice that size. The study also measured scrap exports, checkpoint extortion and the transfer of state assets to private hands.

For Oliveros, these illegal activities are “a perfect substitute for the clientelist economy” of the chavista boom years. “It has consequences in every aspect.” It’s money that feeds legit activities and consumption, but also business investment. Its vast networks involve a considerable number of people who benefit, thus decreasing social tensions. But by benefiting the elite that controls these activities, they decrease the possibilities of political change. “The illicit economy is a central element to understand the economic, political and social dynamic happening right now in Venezuela,” Oliveros says. “It explains part of the current growth of economic activities and consumption.”

For each of the illicit economies studied, Econanalítica used a variety of statistical methodologies. Obviously, estimating illicit economies “is a challenge everywhere in the world because the concept of the illicit economy is precisely tied to something underground, hidden,” says Oliveros. “It’s an approximation to try to quantify what the illicit economy represents in Venezuela. It’s not crazy to think that some of these activities are underestimated.”

A Black Market For Imported or Subsidized Fuel

In 2018, Venezuelans were paying 99.9% less for their gasoline than what they paid in 1986. Thus, subsidized gasoline—the cheapest in the world back then—started to be smuggled to Colombia. When shortages aggravated in early 2020, smuggling networks would reverse as western border states started to demand illegally imported gasoline from Colombia.

At the same time, another type of smuggling would also flourish: with 42% of gasoline in Venezuela subsidized, a parallel market of deviated subsidized gasoline sold for higher prices started. Nowadays, diverted gasoline can reach up to $3.5 per liter. Civilian and military personnel are in charge of distributing gas in the country.

The study, based on interviews with government sources, estimates that around 60% of the country’s production is diverted for illegal sales. Ecoanalítica created an estimation model based on data about the average consumption of fuel in Venezuela, and estimated the profit generated by the diverted 60% using black market prices, which are usually higher than international ones.

A Stable Flow of Drugs

For years, Venezuela has been considered a major transit country for drugs—mainly cocaine—produced in Colombia, shipped from Venezuela to the United States, the Caribbean islands, Central America, Africa and Europe. But according to DEA reports quoted by the study, the situation has worsened as Colombian criminal groups and guerrillas have settled in the country, transporting and storing big quantities in rural areas before exporting them.

Assuming the amount of drugs trafficked by sea remained constant since 2019 and adding up proven seizures reported by other countries and local agencies, concluded that at least 55,500 kilos of cocaine and 7,000 kilos of marihuana transited through Venezuela in 2021, which accounts for a gross margin of $4.9 billion dollars per year, the most profitable of the illicit trades in the study. The firm also used a model elaborated by the Bank of the Republic (Colombia’s central bank) and adapted it to Venezuela’s transit country status.

Open Ports

The bodegón fever is part of the study, which also calculated the profit of illicit port activities. Through over-regulations and centralized and militarized port authorities, says the report, military personnel and state officials—including some bigwigs—have participated in the systematic extortion of both public and private companies.

The highly popular “door-to-door” (puerta a puerta) services, in which courier companies send move-outs or goods directly from the United States or other countries to people’s homes in Venezuela, represent between 20% and 30% of the containers processed annually in Venezuela, says the report. According to sources interviewed by Transparency, courier companies don’t declare the value of the goods inside the container but pay corrupt officials. The real tariffs are pocketed by those who work in ports and customs, instead of SENIAT.

To calculate the profit of this illicit economy, Ecoanalítica compared “the import volumes reported by Venezuela and the volumes registered by the rest of the world and found the discrepancies,” says Oliveros.

Ecoanalítica studied 20 transportation and distribution companies in the first quarter of 2022. Then, measuring variables related to their experience, they collected data from ten of these companies and averaged the answers of the companies to reach a 25% probability of suffering road checkpoint extortion.

The Mining Arc’s Pax Mafiosa

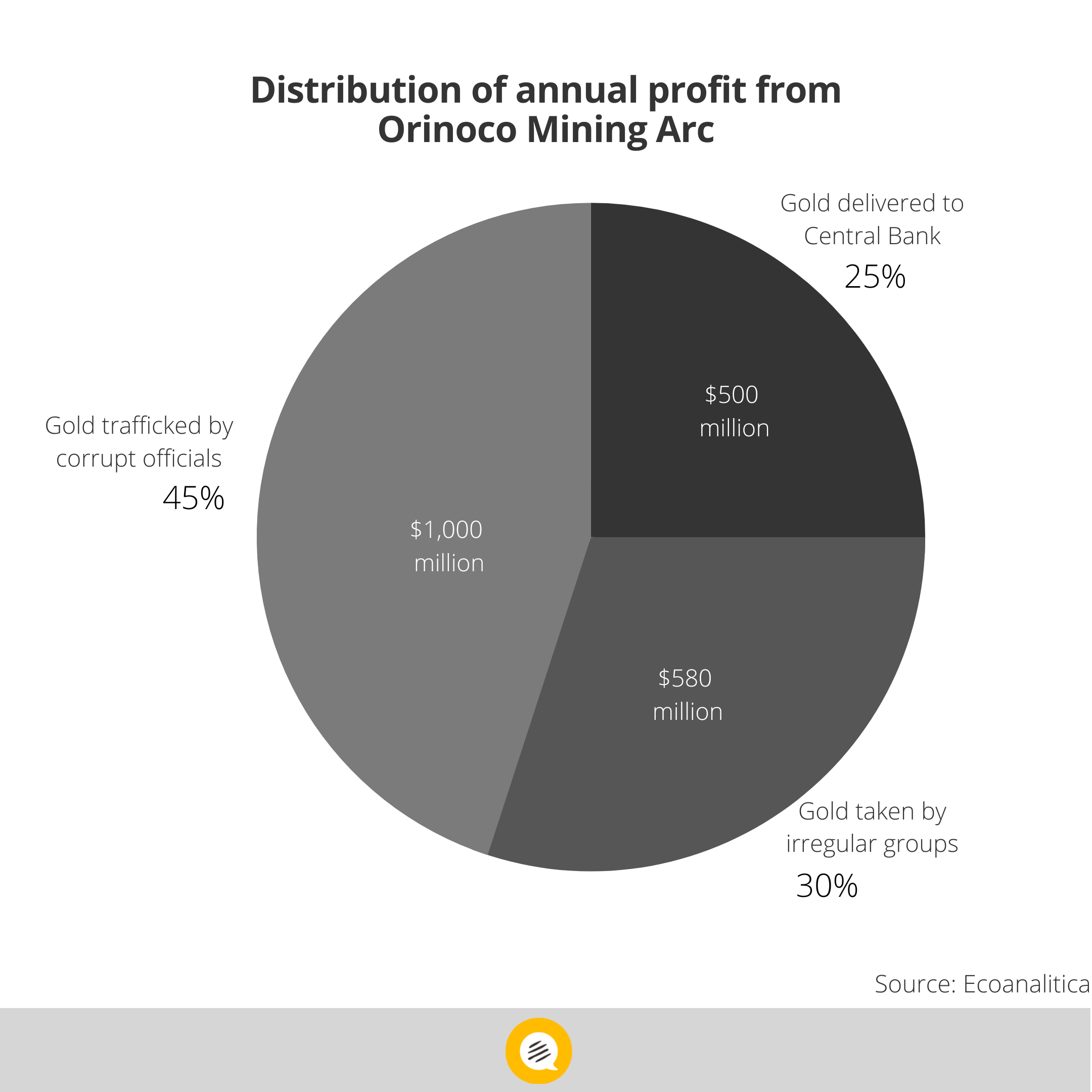

Since the Orinoco Mining Arc was created in 2016, a plethora of public and mixed companies operate in the area under conditions devoid of any transparency and accountability. Even if gold won’t fill the state coffers to the point of compensating for the lost oil income, says De Freitas, the illicit gold trade generated $1.8 billion in 2021 according to Ecoanalítica’s estimations (Venezuela’s oil revenue in 2012 was $21 billion according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration).

According to the study, only around 25% (7.5 to 9 tons per year or between $500-580 million) of the gold being extracted actually reaches the Central Bank of Venezuela (BCV). 30% (7.5-9 tons per year or $500-580M) is taken by irregular criminal groups and the rest—the higher percentage—ends in transactions made by corrupt officials (13.5-17 tons or $900M-1000B per year). Thus, 75% of Venezuela’s gold production goes to irregular groups.

These numbers are similar to those given by an office of the Ministry of Environmental Mining Development in 2018, when the entity admitted that the BCV was getting just 30% (10.5 tons) of the gold production while the rest was smuggled to Guyana, Brazil and the Caribbean islands.

In the discrepancies between the national production data from the Central Bank and that of international organisms, one can see the amount of gold diverted, explains Oliveros. The report also consulted internal sources on this matter.

Not only the mines but the roads can be profitable. A Transparency delegation counted 25 military and police checkpoints in one single road crossing the mining towns. The state and the municipalities in the Orinoco Mining Arc, most of which are governed by ruling party PSUV, also participate in the trade.

Despite so many state entities involved, most miners are not licensed or belong to companies’ payrolls. They don’t comply with security or environmental standards and exploit unauthorized or protected areas, but they extract most of the gold, giving a percentage to criminal groups and selling it to mills that mix it with mercury and also pay a fee to criminal groups. Gold is a currency throughout Bolívar, sometimes more valuable than dollars, and while the law states that the mineral should be sold to the BCV, most is taken out of the country.

The most consolidated sindicatos (gold mafias that started as mining unions)—through cohabitation agreements with other sindicates and security forces—now call themselves “El Sistema”. This extended control of territories and peoples is defined as “criminal co-governments” by Transparency: they manage violence and migration, deal in real estate, and solve family quarrels and business conflicts. The System includes exemplary punishments to dissuade whole populations. “They are now trying to be recognized as groups that seek order in the communities and that seek to help the needy through foundations that distribute food bags, provide outpatient clinics, and repair schools,” says the report.

The study identified 13 criminal groups in Venezuela, including drug cartels, peasant self-defense groups, Colombian paramilitaries, guerrillas, sindicatos, colectivos, and gangs. The funds coming from illegal economies have allowed gangs like Tren de Aragua to expand internationally. Many of them engage in turf wars or alliances with the security forces.

Bolivarian Perestroika?

Regarding the state companies (especially in food, tourism and manufacturing) transferred to the private sector as the government seeks new income, the report mentions most corruption-favoring opacity, protected by the so-called Ley Antibloqueo. For Oliveros, rather than “a standard privatization,’’ these “strategic alliances” or “concession of assets to certain actors, many of them close to the government” leads to “monopolistic structures focused on profit maximization and not benefits for the population.”

The study mentions a sugar mill that could produce 300,000 annual tons of sugar and which the governorship of Sucre transferred to a private company named Corporación Tecnoagro at some point between 2020 and 2021. It also mentions the Alba Caracas Hotel, previously the Caracas Hilton expropriated by Hugo Chávez in 2007, which was transferred in a “commercial alliance” to unidentified Turkish businessmen last year. Another case is the unilateral cancellation of at least 50 pre-existent concessions of PDVSA gas stations that were later handed to new owners.

Scrapping the Industries Away

While illicit trades and criminal groups are flourishing in the shadow of the collapse of the oil industry, the old industries are also becoming part of another rising irregular (though not illicit) economy: the sale and commercialization of ferrous scrap belonging to state assets such as PDVSA iron pipelines that were used to bring gasoline from La Guaira to Caracas, wind turbines in Bolívar and Zulia, more than 150 major unfinished public works or even drilling rigs in Anzoátegui.

“The public sector seems to sell it to the private sector, which then exports it,” says Oliveros, “That’s how we got the information.” According to De Freitas, big trucks then transport the scrap from recollection centers to the ports—mainly from the east towards Güiria—to be exported in tons to other countries: mainly Turkey (92.32%), followed by Thailand (4.78%) and Portugal (1.34%).

These exports skyrocketed in 2021: in 2012, Venezuela exported less than 100,000 tons of scrap metals and it was still under 200,000 tons by 2020. Yet, in 2021, Venezuela—desperate for new income—exported 1,013,990 tons of ferrous scrap, according to TradeMap numbers: this represents an annual income of $454 million, rising from $150 million in 2020 and $75 million in 2012. “It’s an asset depredation that will have a significant impact in the medium and long term when Venezuela seeks to reactivate its heavy industries,” explains Oliveros.

With heavy industries scrapped and illegal markets making up a higher share of Venezuela’s GDP than oil or any other economic activity, it’s clear that these illicit trades are not only shaping Venezuela’s present but also its future. “If we can advance towards reconquering the legality of the rule of law it will be through very complex negotiation processes,” says De Freitas.

For Oliveros, no country is doomed. “The moment Venezuela has a transition towards democracy or some sort of change, it is important to consider the presence of the black economy and those responsible for generating a dismantling scheme based on that,” he says, “I don’t believe this will happen overnight but it’s an important factor to evaluate in the transition. Other countries did it.”

Caracas Chronicles is 100% reader-supported.

We’ve been able to hang on for 22 years in one of the craziest media landscapes in the world. We’ve seen different media outlets in Venezuela (and abroad) closing shop, something we’re looking to avoid at all costs. Your collaboration goes a long way in helping us weather the storm.

Donate